Julia Bullock, soprano: ‘Violence underscores the culture of the United States. I am so relieved to not have to live there anymore’

The U.S. singer stars in Katie Mitchell’s feminist version of Handel’s oratorio ‘Theodora’ at Madrid’s Teatro Real

On a table in the dressing room at Madrid’s Teatro Real where our talk is to take place rests a promotional pamphlet. It shows a woman from behind in a blonde wig and dress covered in silver sequins. She wields a kitchen spoon as if it were a weapon. This is Theodora, the titular character from Handel’s famous oratorio, which is being brought to the Teatro Real’s stage by famed British director Katie Mitchell.

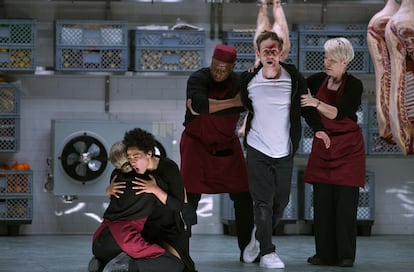

In Mitchell’s reimagining, Theodora has shaken off her original passivity and embraced the opposite qualities: defiance and a fighting spirit. Julia Bullock, the 37-year-old soprano who plays this role, enters said room as if it were hers, puts her purse and coat aside and easefully takes over a sofa. Feminist, activist, winner of the Grammy for Best Classical Solo Vocal Album in 2023, Bullock is a person with clear convictions. So clear, that thanks to her, the Royal Opera House in London hired an intimacy coordinator for the first time in its history to stage scenes featuring sex and violence in the version of Theodora that is now being presented in Madrid.

In 2023, she also convinced Barcelona’s Gran Teatre del Liceu to make a similar hiring decision for its production of Antony and Cleopatra, the opera that John Adams created to showcase Bullock herself. “Barcelona was not understanding or on board, so I just wrote to the director and said, ‘This is essential for me and either we can [have an intimacy coordinator] or I can’t be a part of it,” she recounts.

She goes on to say: “All that Theodora wants in her life is love and acceptance and anything that is not on that path of love and acceptance she will not tolerate. That is the part of her that is extreme, and that makes her behave in extreme ways.” The African American soprano, who once battled severe addiction and a psychological condition that at times left her unable to sing — or even speak — appears unaware of the parallels she shares with her character. Her expanding professional commitments in Europe have prompted her to relocate from the United States to Munich.

Question. I have to start by asking you about Donald Trump.

Answer. I don’t have much to … [stops for a moment to consider her response] I was surprised by the popular vote. To have him be elected the way he was, was upsetting.

Q. Why do you think it happened again?

A. The United States is — the way our country was founded, the genocides that happened, the lack of reckoning and reconciliation around centuries of violence — I think that it is still something that is underscoring the entire culture in the U.S., from its inability to deal with gun violence in a serious way to its inability to uphold the values of protecting women’s rights. I am so relieved, personally, to not have to live there anymore. And this is a weird statement to say about a country that is so prideful and is held in this position, or has wanted to hold itself, at least, in this position of being one of the most liberal, democratic entities in the world.

Q. Do you think having a woman at the top of the ticket affected the outcome?

A. There is that supremacist mindset, and the patriarchal mindset that is rooted in. Of course that was an influence. I guess I didn’t realize how widespread white supremacy was.

Q. Are you very worried about what could happen?

A. I know how it impacts people on micro levels, but when it comes to an extreme moment like this, in something as important as this particular election — it was just revealing. It was revealing.

Q. Is this version of Theodora an attack on the patriarchy?

A. Yes. I think Katie did not want to watch any more women die on stage, unless it is for an absolutely necessary reason. She will find any opportunity to allow women to live and care for each other.

Q. I imagine that you’re referring to the end of the play. In this version, Theodora not only doesn’t die, she becomes a killer.

A. Yes. Honestly, when Katie first told me about how she wanted to end the show, I was concerned and I guess not fully convinced, because I had been so indoctrinated with this idea of Theodora being a sacrificial character. But as we went through the process of staging it, and when we finally got to the final scene of the show, Katie just said, “Julia, someone’s going hand you a gun and I just want you to get yourself out.” I’m seeing this stream of dead bodies in the path, and the character who assaulted me in the scene before walks in and initially I just melt down and I thought, “I’m just going to touch this man and let him pass away.” But actually, shooting him was inevitable behavior. The reality for all the characters in this world of Theodora is that they cannot escape the violence that has insidiously crept into all elements of their beings. It’s just heartbreaking.

Q. You no longer have doubts about the ending?

A. No. I have to just continuously bring it back to what Handel and Morell [the composer’s librettist] wrote: a message of liberty and life. In that way, it kind of makes this interpretation inevitable, or it would have been inevitable at some time.

Q. Is this version of Theodora’s personality in the original libretto?

A. Absolutely. She has tremendous faith, faith in herself, faith in the people she loves. She does not doubt it at any point in the piece. She is so self-actualized and secure, and that is a really interesting personality to play, because it’s not that she doesn’t get shattered in the piece, but she still keeps this inner sense of herself. In the libretto, there’s just a few lines that Katie took out, the more Christian statements that were leaning towards patriarchy. But again, the core of it is all there and in fact, they’ve even inserted an extra aria at the end! [laughs]

Q. You said that this reinterpretation was somehow inevitable. Do you think this will also be inevitable in other operas?

A. I think most operatic pieces have messages that are really telling about ourselves, and it’s just about which of those messages you want to make clear, and which ones do we actually not need to hear over and over again? So yes, I think there is an opportunity in every single existing work of the canon to frame it in a way that does not show that abuse and oppression is the ultimate end. We don’t have to necessarily keep repeating patterns.

Q. This staging has also changed patterns of production. Much has been made of its use of an intimacy coordinator. What is their role?

A. We do not know what traumas actors are carrying with them, and they can be triggered in a rehearsal [she seems to lose her breath for a moment]. Sorry, I’m stumbling a little bit because I haven’t written about this publicly yet. I was going to, over the course of this show, but maybe just to explain why I think it’s so important; in our first session with Ita [O’Brien, the intimacy coordinator], we touch our entire bodies, checking to see what areas are OK and comfortable and which are not. We were on the initial assault scene in the kitchen and everything was essentially on balance. No breasts, you even explore like, how high up between your legs you can go, all of this. You explore your feet, all of it. But there was one move that Ed, my colleague, was asked to explore, out of character, and tears just started streaming down my face and I said, “I’m sorry, I’m so sorry. I’m totally fine,” while I’m just wiping tears away. I was weeping, but I was like, “let’s just keep going.” Ita said, “Stop. This is exactly the reason why we do this. You’ve clearly been triggered and we don’t need to discuss what that trigger moment was or why it happened, but it has happened and that means that this move does not need to be part of our staging.” It wasn’t until we got into the run of the shows, like three weeks later, that I woke up in the middle of the night and realized what the trigger moment was from. It was from my life in my twenties, but that does not need to be part of the show, and my nervous system did not need to relive that moment over the course of those rehearsals and weeks. Yes, we want our performers to be revealing, but not at the expense of their emotional, physical or psychological health.

Q. Does that happen a lot in the world of opera?

A. It’s happened to me and after some performances I’ll speak to certain artists and ask how they are, and they say, “It’s actually been really difficult because I can’t talk to any of my male colleagues anymore, or I’m crying before every show because I’m afraid of what’s going to happen out there.” That’s just plain and simple abuse, even if that artist is “willing” to be abused. So [intimacy coordinators are] a shift in culture that is really positive.

Q. Even if the artist has taken on the role?

A. That is irrelevant. I went through years of doing scenes where I thought to myself, “I’m such a good actress.” I think actually I was just living out my personal trauma on stage, and it came to interfere with my ability to sing and just live my life outside of a performance space.

Q. It was the first time an intimacy coordinator had worked at the London Royal Opera House.

A. Yes, I shared a story about an experience that I had that was really upsetting with Katie and she let me know a week before we started rehearsals that we were going to have an intimacy coordinator. She really heard me during that session. I felt so relieved that she was taking the demand that [the show] was going to be putting on her performers so seriously.

Q. Then came Spain’s first time, with the staging of Anthony and Cleopatra at the Liceu de Barcelona.

A. Initially, Barcelona was not understanding or on board, so I just wrote to the director and said, “This is essential for me and either we can have an intimacy coordinator or I can’t be a part of it.”

Q. You once said you that you didn’t consider art as therapy. What did you mean by that?

A. There are art therapies that exist, music therapy, dance therapy. I know every day when I sing, it’s almost like a recalibration of my system. That is therapeutic, no doubt about it. But in the space where we are making a work to be experienced by other people, you have to organize your emotions so that they are legible. I do not want to be disassociated while I am on stage. It means you’re not crafting an experience, it means that you’re not tracking things that are still imprinting on you and your nervous system. Because of the subject matter that is in most operas — they can be very violent. I now have tools to organize myself so that I’m making conscious decisions. There are other places to work on recovery stuff.

Q. Maybe it’s because of that consciousness of the stage that your acting talent is so widely recognized.

A. Well, every single opera singer I’m in love with was an amazing actor. If I watch videos of singers in the 1930s, 1940s, they’re singing with such power, such vocal prowess. But if I turn the sound off, they’re still luminous and so clear in their communication. And I guess that aesthetic is something I wanted to take on and incorporate into my own work.

Q. Can that affect your vocal work?

A. Yes, my vocalism can become a little compromised. I’m still working on that, because I think you can find a balance to hold it all. That’s the craft of being an opera singer.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.