The true history of architectural aberrations

Katsuhiko Akasegawa called the dead-end urban structures he came across ‘thomasson’ after a successful U.S. baseball player who moved to Japan and got nowhere

You have probably seen at some point, in a building or on a street, more than one architectural oddity that serves for nothing: a door that opens onto a void, a staircase that abruptly bumps into a wall or perhaps a balcony with no way of accessing it. And perhaps you have wondered at that moment what the architect who designed such an anomaly was thinking. Well, in fact, these impossible architectural structures have a name: “thomasson.” They are now recognized as a type of art and their name derives from an unfortunate baseball player called Gary Thomasson.

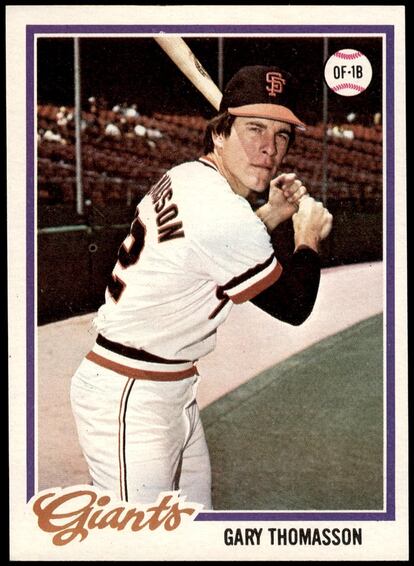

In 1980, after a stellar MLB career as a first baseman, primarily with the San Francisco Giants, Thomasson was the protagonist of one of the most talked-about trades in baseball history: he went to Japan.

Baseball was — and still is — the most popular sport in Japan, almost akin to a religion, and, although more than one baseball hero had already played there, never before had a Japanese team signed an American player in his prime. Thomasson’s trade to the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants made headlines because he was just 30 and in top form. Moreover, he cost more than $2 million and his salary easily trumped those of the rest of the players in the Japanese league.

Fans of the Yomiuri Giants were hoping for the best from Thomasson. Among them was a 43-year-old artist named Katsuhiko Akasegawa, known in the art world as Genpei. Besides being a Giants fan, Akasegawa was one of the brightest avant-garde figures in postwar Japanese art. His most famous work was a series of 1,000-yen banknotes, which he did not consider as counterfeit currency but as “a mock-up of banknotes, just as a model of an airplane is not an airplane.” Despite this explanation, the authorities ended up taking him to court.

During the trial, Genpei insisted that the banknotes were art, turning his appearance in court into a performance in which he and other contemporary artists reflected on the meaning of art. In the end, and after several appeals, the Supreme Court of Japan gave Akasegawa a suspended three-month sentence in 1970; in other words, he did not go to jail and, in fact, his banknote-prints soared in popularity to the point that they are currently exhibited at the MoMA in New York.

However, Genpei’s greatest contribution to art would come in 1972 when, while walking down a Tokyo street, he found a staircase that led into a wall with no door or landing. Subsequently, he began to explore his urban environment in search of such architectural aberrations, considering them to be relics of a city built under the city. They included bridges that crossed nothing and tunnels that led nowhere, doors that opened onto a void, inaccessible balconies, and inclined railings with no stairs to support them. These were points of contact between the different layers of a city that, once fallen into disuse, ended up as archaeological sites.

For eight years, Genpei tried unsuccessfully to make sense of these structures, which he considered hyper-artistic... until Gary Thomasson joined the Yomiuri Giants.

Despite his success in the U.S., Thomasson’s career in Tokyo was worse than disappointing: in his first season he almost broke the Japanese record for strikeouts and his second season was spent almost entirely on the bench, until he injured his knee and quit baseball altogether. Understandably, fans were angry at a player who had cost so much money and was paid so much — all except Genpei Akasegawa, who had just found a label for the absolutely useless structures that were nothing but a reminder of when they served a purpose, like Thomasson.

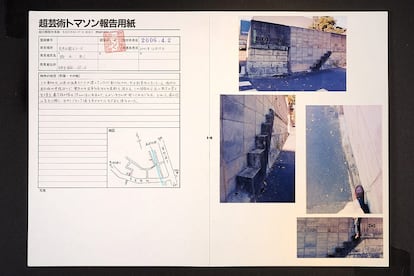

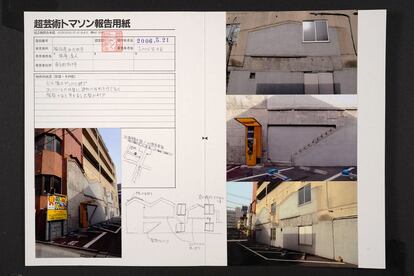

In 1981, Genpei founded the Thomasson Observation Center, where he collected photographs of these urban anomalies, which were then published in Super Photo Magazine, which, in turn, encouraged readers to send photos of the thomasson they came across. Thus, the search for thomasson became one of the favorite pastimes of Japanese photography enthusiasts, a quest that, in one way or another, continues to this day, not just in Japan but all over the world, more as a humorous and recreational activity than anything that might be considered artistic.

Genpei Akasegawa died in 2014 at the age of 77 while Gary Thomasson currently lives in San Diego and would surely not be remembered if it were not for the fact that a Japanese artist decided to use his name to label the redundant structures remaining from our cities’ past.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.