‘Baumgartner’: Love in the moment of truth

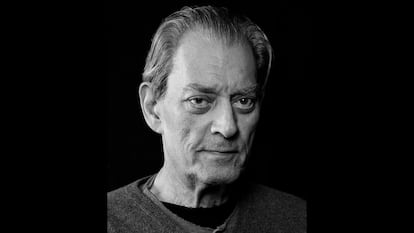

In his new novel, Paul Auster maintains his faith in fiction and love despite living – as he says – in ‘Cancerland’

Is there anything more plausible than the tragic “madness of grief” that Paul Auster tells us about in Baumgartner? In his novel, despite living – as he himself says – “in the country of Cancerland,” he continues to maintain an unconditional faith in fiction as well as an unconditional faith in love, in the face of the strident stupor that reality produces.

By making the “madness of grief” experienced by his main character — the widower Baumgartner — so plausible, Auster creates the ideal narrative path to reach a supreme moment, worthy of any anthology of love stories: the telephone rings in the night and the dilapidated widower hears (from beyond the grave) the voice of his wife, who died nine years earlier.

The fraction of reality within this episode creates sufficient conditions for the reader to be trapped by the author’s skill in the art of fiction. From that magical and masterful moment, Auster sets the emotional state that will mark the rest of the novel. He creates a story with a kind of naturalness in modern writing that’s usually attributed to the highly-regarded French novelist Stendhal, one of the monarchs of realism and the genre of passion.

In Baumgartner, we’re told that if we’re lucky enough to be closely connected to another person — so close that the other person is more important than us — life doesn’t just become possible… life is lived to the fullest. Which is like saying that — even if your loved one has passed away — love is more eternal than the silence of death. And, at the end of our days, it only counts if you have loved someone and that they have loved you.

“Has love become something undervalued in the contemporary world, perhaps because other values provoke more interest?” This is one of the questions that Spanish writer David Trueba asks Woody Allen in his recently released and brilliant interview-based film A Day in New York. Woody Allen’s response brings us back to Auster’s novel: “I think that if you watch movies set in the present day, or period pieces, or even if you read books from today, love is always there.”

“Love and crime,” Woody then clarifies. And crime refers to death — to the “madness of grief” — and the classic notion of love and death, to which the third theme always needs to be added: the passage of time. This is a cliché that cannot be missing in the triangle of themes that are always present.

For Woody Allen, love and death “have remained stable, from Greek tragedy until now, through Shakespeare, Chekhov… and even Scorsese.” He says this to David Trueba with the same prodigious serenity that he maintains throughout the entire film-interview, where he subtracts any type of pomp from his career. He falls into humility, even while knowing full well that the problem with humility is that you can’t brag about it. But that’s what Woody seems to be interested in: not bragging about anything, as if he wants to tell us that everything he filmed was easy; it all came together in the end. And only love – as Auster tells us in Baumgartner — counts at the moment of truth.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.