New York Metropolitan ‘uncovers’ close ties between Africa and the Byzantine Empire

An exhibition traces centuries of the history, traditions and artistic influences of the two shores of the Mediterranean through 200 pieces, some of them being shown for the first time

Amidst the lavish programming of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, which each year presents around 20 major exhibitions, minor shows can go unnoticed, those that seem written in small letters among the great names in art history (last year, for example, there was a monographic exhibition dedicated to sunflowers in the work of Van Gogh, and a vibrant dialogue between Manet and Degas). Chamber music, as opposed to the colossal symphonies of the most-visited shows. But these small exhibitions, such as the one dedicated to unveiling the artistic relationship between Africa and Byzantium, make the Met what it is: the flagship of U.S. cultural institutions.

Africa & Byzantium, organized in collaboration with the Cleveland Museum of Art, is a joy in many respects. Over the course of nearly 200 works, many of them previously unseen in the U.S., it surveys the tradition of Byzantine art and culture in North and East Africa, from the fourth to 15th century and its aftermath. Africa & Byzantium sheds light on an underrepresented area of art history and showcases a new field of interdisciplinary studies on medieval Africa, a period nearly unexplored by major galleries and museums. Although Byzantium was a vast empire that spanned parts of Africa, Europe and Asia, its close connections with Africa have been the subject of little study.

These two worlds had a closer relationship than has been assumed. The Mediterranean which separated and at the same time united them was witness to the traffic of goods and people that passed between the two coasts, similar to today’s path of the migrants who escape war and poverty en route to Europe. From its capital in Constantinople, a fleeting symbol of intrigue, opacity and opulence, the Byzantine Empire (331-1435) ruled much of North Africa for centuries, during which primitive Christianity developed in the kingdoms of the Horn of Africa from the fourth to seventh century. But the official religion of the empire did not prevent the development of the various religious — and artistic — traditions that flourished in Tunisia, Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia between the eight and 15th centuries. That is why symbols of the three religions run through the exhibition as a thread of coexistence: alongside crosses, there are seven-armed candelabras and crescent moons; also, anthropomorphic representations prior to the prohibition of images in Islam. Of particular note are the menorahs of the Hammam Lif synagogue, in what is now southern Tunisia.

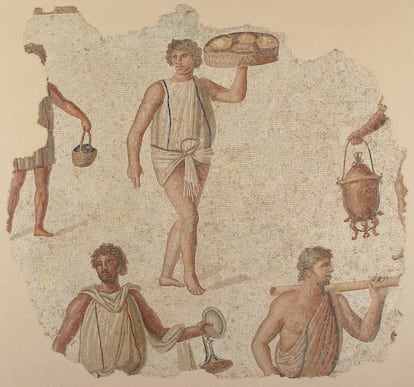

Faith, politics and trade by land and sea tie these traditions to Byzantium, giving rise to a fertile exchange of artistic techniques and beliefs. The pieces on display in the exhibition span nearly 2,000 years in a wide range of media, from monumental frescoes, mosaics, panel paintings and metalwork, to jewelry, ceramics and illuminated manuscripts, not to mention several examples of precious inlaid furniture or finely carved doors. Numerous portraits in the tradition of Al Fayum (Egypt) animate the Cretan iconographic school and the mosaics of Carthage. They are displays of beauty and rarity, of a fascinating Golden Age so far overshadowed, such as the beautiful icon of St. George, from the 13th century, in Egypt. Or the mosaic of Our Lady of Carthage (dated between the fourth and fifth centuries), which represents the personification of the Tunisian city.

An exhibition that destroys ethnocentrism

Africa & Byzantium is a challenging exhibition, not only because many of the objects are visiting New York for the first time, but also because it destroys ethnocentrism (or Eurocentrism, if that term can be used to refer to the eastern corner of Byzantium): if some of the best icons were painted in Egypt, where is the center and where is the periphery? Who was the master and who were the disciples? These are quite pertinent questions whenever we talk about tradition and cultural creation. The exhibition demolishes expectations and raises doubts: when does Byzantium begin and, above all, where does it end? St. Augustine of Hippo, who is quoted in the show, asked himself the same question in the year 416, of his congregation in Carthage: “Who now knows which peoples in the Roman Empire were what, since all have become Romans and all are named Romans?”

“This stunning exhibition brings new focus and scholarship to an understudied field, expanding our knowledge of Byzantine and Early Christian Art within an expansive worldview,” said Maz Hollein, director and CEO of the Met, in the exhibition’s press release. “Through spectacular and widely unknown works of art, Africa & Byzantium illuminates the development, continuity, and adaptation of Byzantine art and culture in North Africa and the Horn of Africa, recentering African artistic contributions to the pre-modern period.”

Africa & Byzantium traces the three stages of exchange between the two shores of the empire. From the fourth to the seventh century, early Byzantine visual and intellectual culture was shaped by wealthy patrons, artists and religious leaders from North Africa, the region that was home to some of the richest provinces of the late Roman and early Byzantine Empires. From the eight to 16th centuries, specific Christian religious and artistic traditions flourished in the African kingdoms, and in the last stage, from the 17th to the 20th century, Ethiopian and Coptic artists in East Africa were inspired by Roman and Byzantine art.

Byzantium was born when the first Christian ruler of Rome, Constantine the Great, moved the imperial capital east, to the ancient city of Byzantium, renamed Constantinople (now Istanbul). From then on, a new art, inspired by Greek and Roman traditions and transformed by intellectual and spiritual influences from the Far East, evolved and spread outward, raising questions as to where Byzantium began and ended.

For those not fortunate enough to visit the exhibition in situ, running alongside one end of the Met’s Greek gallery, an excellent 20-minute video in which Andrea Achi, the Met’s associate curator of Byzantine art, walks through and explains the show, may be a good substitute. “Bringing together new research from over 40 scholars worldwide, the exhibition addresses how diverse communities connected to Byzantium flourished in African empires and kingdoms for over a thousand years. It will broaden public understanding of the Byzantine world, its reach, and transcultural authority and examine the critical role of early African Christian civilizations in this creative sphere,” states Achi in the exhibition’s press release. The exhibition will travel to the Cleveland Museum of Art after it closes in New York on March 3.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.