Why only women’s clothing has a zipper on the back: The birth of a provocative invention that changed our way of dressing

Created in 1913 to make the dressing process more practical, it was used by sailors, enraged the puritans and even reached the Moon. This invention also became part of the feminist debate, as back zippers took away women’s independence when it came to dressing

Where have I seen them before? In March, South Korean model HoYeon Jung opened the catwalk for Louis Vuitton’s women’s collection with a skirt and bodysuit, equipped with zippers of exaggerated proportions. According to fashion designer Nicolas Ghesquière, those were the largest zippers ever made. The process of enlarging and exaggerating this element led him to also resize other garments and details. Basically, he created the brand’s Summer 2023 collection out of zippers.

A leap in time takes us to the preview of the French brand’s Summer 2024 collection. Huge zippers are no longer seen on the garments… but one dizzying zip stole the show at the presentation. This was part of Zendaya’s stunning white dress. The result was so powerful that the image made the rounds on social media: “Zendaya’s zipper dress in 2023 is Liz Hurley’s must-see dress in 1994,” read a tweet, referencing the Versace outfit from nearly 20 years ago that forever changed the concept of fashion on the red carpet.

Today’s Louis Vuitton zippers are a nostalgic element taken from one of Ghesquière’s first collections, when he was the French brand’s creative director a decade ago. It’s now been reinterpreted in a new size… and its impact has certainly resonated. Although we might have thought that zippers had already reached their peak, the 2023 and 2024 fashion collections reveal that this trend was simply waiting its turn. Exposed zippers have reappeared, dotting the collections of Eckhaus Latta or Sukeina. They have their roots in Ghesquière’s creations, but have also been popularized by brands such as the Italian luxury fashion house Marni. In 2010, the company released a series of dresses and blouses with exposed zippers that the fashion world couldn’t get enough of. And, in 2011, Victoria Beckham earned her reputation as a fashion designer by releasing a now-iconic dress with a back zipper. Fast-forward 12 years, to a blog by the famous Hollywood stylist Rachel Zoe, in which she confirms the return of this trend: “The exposed zipper is everywhere.”

Brief history of the zipper

In reality, the road to success for the humble zipper was long. This mechanical marvel was created thanks to the work of several inventors. However, — as noted by writer Mery Bellis on ThoughtCo.com — no inventor was able to convince the general public to accept it as part of everyday life. Rather, it was magazines and the fashion industry that turned the novelty zipper into the popular item that it is today.

The story, Bellis notes, begins with Elias Howe, Jr. (1819-1867), the inventor of the sewing machine. He received a patent in 1851 for an “automatic, continuous clothing closer.” But — perhaps due to the success of his other great invention — his proto-zipper was left on hold. It took almost half-a-century until someone rethought Howe’s idea. It was a Chicago inventor named Whitcomb Judson who marketed a device in 1893, which he called the “clasp locker.” It was designed to close shoes… but it was a bit complicated.

Finally, in December 1913, a Swedish engineer living in Philadelphia named Gideon Sundbäck came up with the idea of the modern zipper. Sundbäck increased the number of fastening elements in two opposing rows of teeth, managing to join them with a sliding piece. His “separable closure” was patented in 1917.

Sundbäck also created the machine to make this new zipper. But its name — zipper — wasn’t his idea. That came from the B.F. Goodrich Company, a firm that decided to put this closure on its new rubber boots. The sound it made — “zzzzzip” — resulted in the name.

In the early years, zippers were used to close rubber boots and tobacco bags. It took almost two decades to convince the fashion industry that this novel closure had sensational potential. In the 1930s, a campaign for children’s clothing with zippers began as a way to promote self-sufficiency in young children, since zippers allowed them to dress themselves without requiring much help. Designer Elsa Schiaparelli — a reference in the world of surrealist design — was the first to include zippers in her avant-garde dresses. She promoted them to become more popular in women’s clothing, although her fashion style was still more conceptual than everyday.

Zippers in the fashion conversation

In 1937, the American magazine Esquire launched a survey of its readers, which it called “the battle of the fly.” This was about whether the button fly or zipper fly was better. The second won.

Just kidding. The truth is that no such article appears in the magazine’s online archive (which covers all articles since 1933). However, this anecdote has been repeated in numerous publications… including Esquire magazine itself in 2014. It seems likely that the story of “the battle of the fly” is the recycling of a phrase from the book Zipper: An Exploration in Novelty (1994) by Robert Friedel, which discusses the marketing effort of Talon, the main competitor of the B.F. Goodrich Company.

The Esquire archives have an interesting (and real) article written by John Berendt from May 1, 1989, which is dedicated to the zipper: “Zippers were still a novelty in 1932… they were a symbol of the mechanical future and dehumanization that awaited us all.” Custom tailors disdained zipper flies as vulgar, while mass manufacturers claimed they were too expensive: a zipper added a dollar to the cost of a pair of pants; buttons cost only two cents. That’s how things stood until 1934, when the Prince of Wales, the Duke of York and his second cousin Dickie Mountbatten suddenly started wearing zipper flies. According to the Smithsonian Institution, thereafter, the zipper was suddenly declared the “new idea in men’s tailoring.”

After a time, the zipper finally won over the general public with its practicality. Zippers were incorporated into the uniforms of American sailors and, as fashion proposed less and less formal clothing, the zipper gained popularity. By World War II, zippers had become widely used in Europe and North America. After the war, they spread to the rest of the world. The first urban garment to incorporate it was the leather jacket. And, in the 1950s, NASA began manufacturing space suits with zippers capable of retaining air pressure in the vacuum of space. They were used by astronauts during the Apollo 11 mission in July 1969, the first Moon landing.

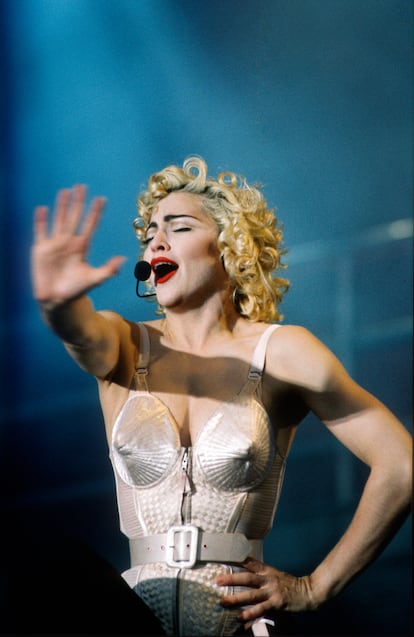

Today, we could say that the zipper is a radically practical invention. But still, controversy has intermittently peppered its history. In the 1920s and 1930s, they were frowned upon… especially in women’s clothing. This was because they allowed one to undress more quickly and, therefore, supposedly encouraged sexual activity. In fact, musical director Busby Berkeley took advantage of the tantalizingly promiscuous possibilities of the zipper by presenting one made of women in the film Footlight Parade, cementing the erotic component that would subsequently be associated with zippers. Many years later, Madonna would exploit this idea, by wearing a corset made by Jean Paul Gaultier for her Blond Ambition World Tour in 1990.

Going back to the origins, in the 1940s, zippers moved from the front or sides of clothing to the back, thanks to masters like Cristóbal Balenciaga. The zipper then became a common resource for outfits… but curiously, this was always exclusively in the realm of women’s clothing.

A current review of this pattern raises questions as to why only women’s clothing has a zipper on the back. Esthetic reasons can be given — after all, this type of back closure allows the garment to have an uninterrupted front, something especially interesting in thin or tight fabrics. But another possible reading is that back zippers exist only in women’s clothing because of the idea that a woman only goes from her parents’ house to her husband’s (as she needs help to dress and undress).

In an interesting reflection on the matter, journalist Celeste Headlee — the author of the book We Need to Talk: How to Have Conversations That Matter — has written a piece on the self-publishing platform Swaay. She discusses the freedoms that women have been permitted to have with clothing, which each era has arranged for her. The zipper in the back, for instance, could be a patriarchal reflection of how women should dress.

“There are four sides to my body and three of them are absolutely perfect for seeing a zipper, getting a good grip on it, and zipping it up. So why? Why, in the name of all that is holy, do clothesmakers insist on putting the zipper on the one side of my body that I can’t see and can’t reach without engaging in extreme yoga? To me, this is a feminist issue.”

Headlee continues: “Do men have zippers and buttons on the backs of their clothing? Is there a single piece of men’s clothing that puts the zipper in the back? No! It’s only women whose clothing requires them to have help in order to get dressed. It’s a continuation of discrimination against single women.”

To this day, there are still gender differences when it comes to placing zippers on clothing. While in women’s fashion they’re usually closed with the left hand, in men’s fashion, they’re closed with the right. This is because of a legacy that predates the zipper, when women’s buttons were designed for someone else to dress them.

The zipper has also made its way into pop culture. Marlon Brando (The Wild One, 1953) and James Dean (Rebel Without a Cause, 1955) created the image of the tough and rugged mid-century man… all thanks to a biker jacket decorated with zippers.

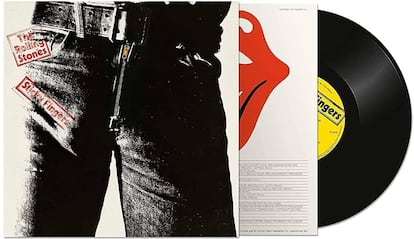

Two decades later, the zipper kicked up dust again. In 1971, the Rolling Stones released their legendary album Sticky Fingers, with a cover designed by none other than Andy Warhol. The original idea — photographed by Warhol’s art collective, The Factory — showed a close-up of the fly of a man (supposedly Mick Jagger) in very tight, revealing jeans, with a zipper that came down. But that cover was very expensive to produce and damaged the vinyl. So, finally, only the package photo was left. The image was a scandal: in some countries, it was censored for obscenity, which led to alternative covers being designed.

Why do (almost) all zippers say YKK?

Look at any zipper on the clothes you’re wearing right now — on your pants, on your jacket, or on your bag. You see the letters YKK, right? But this engraving isn’t witchcraft. The acronym means “Yoshida Kōgyō Kabushiki,” or “Yoshida Manufacturing Corporation” in English. This is the name of the company that was founded in 1934 by Japanese manufacturer Tadao Yoshida. Today, the firm manufactures more than 1.2 million miles of zippers each year, or about seven billion units (according to data from Forbes). Almost two centuries after the original zipper was invented, it continues to maintain its popularity in an omnipresent fashion.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.