The 160 lives of Willie Nelson, the progressive country legend who got his start in a Methodist church

The 90-year-old musician from Texas releases his new book to coincide with his induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

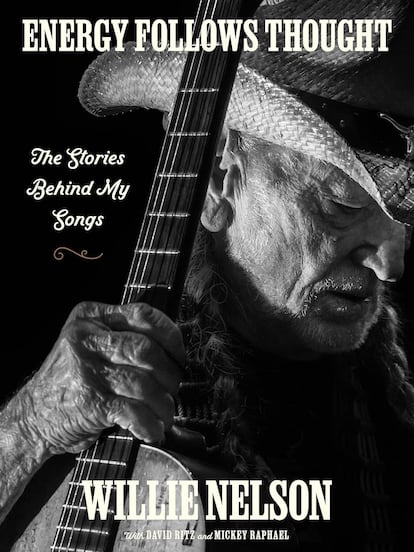

Willie Nelson says one of his favorite songs from his nearly seven-decade career is Permanently Lonely. The country legend first played it live in 1966. Two years later, he recorded it for the album Good Times. Since then, he has recorded the song at a rate of about once a decade until 2014, the last time. What makes the song one of his favorites? The musician claims it’s the chance to take on a completely different point of view than his own — in this case, a man who borders on misogyny and wishes misery on his ex-partner after a breakup. “Intense drama makes good stories. Tortured passion makes good songs,” Nelson writes in his book Energy Follows Thought, a popular mantra among his musicians.

The publication was released in the United States this week. Nelson co-authored the book with David Ritz and Mickey Raphael, who has played harmonica for the musician since 1973. It is the artist’s sixth book and the first in which he tells the stories behind 160 of the compositions that have earned him a special place in American music. The new release also coincides with Nelson’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, in a ceremony to be held this Friday at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn. His fellow inductees include Kate Bush, Queen Latifah, Rage Against the Machine, Sheryl Crow, George Michael and The Spinners.

No one in the class of 2023 has had a greater influence on music than Willie Nelson. Any doubt about that was dispelled on April 29, his 90th birthday. The industry paid tribute to him in a two-night concert at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles. The event was called Long Story Short and featured 45 special guests. More than a story, the gathering was a journey through various musical genres of the group of characters that Nelson has created in his songs. In addition to country music, jazz, rock, blues, gospel and Americana were played at the Hollywood Bowl by performers as varied as Keith Richards, Kris Kristofferson, Beck, Snoop Dogg, Ziggy Marley, Norah Jones, Beck, Emmylou Harris, The Lumineers and Lukas Nelson, Willie’s son and the lead singer of the group Promise of the Real.

Willie Nelson was born in 1933 in a town halfway between Dallas and Austin, Texas. Along with his brother Bobby, Willie was raised by his grandparents, who were musicians and Methodist parishioners. Nelson has been enshrined in the Country Hall of Fame since 1993, when he was first recognized for his contribution to this genre with deep roots in the rural world. After a stint in the Air Force in the 1950s, Nelson went on to play in several state bands. He was also a DJ on radio stations. In 1960, he moved to Nashville, Tennessee, the musical capital of the South, where he became one of the hardest working songwriters in the field.

His legendary career began with one lucky night. Nelson arrived in Nashville with a small, worn vinyl record that included Crazy, which Nelson sang in his slightly offkey baritone voice. One night, a certain Charlie Dick heard it. He liked the lyrics so much that around 1 a.m., he took Nelson (and his record) to meet his wife, the popular singer Patsy Cline. “I stopped being poor because Patsy liked it,” Nelson writes.

The success of Crazy didn’t just fill his pockets. It also confirmed for him that composing songs — which he started doing at age 15 — was worthwhile. “It convinced me at a time when I wasn’t entirely sure of my talent for writing that it would be crazy to stop,” he says in Energy Follows Thought. After a pair of singles in 1962, Nelson’s long career took off, including 73 albums, twelve Grammys, a Kennedy Center award and activism in favor of environmental causes, indigenous people and farmers. He also advocates the legalization of marijuana by presiding over the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML). Over the decades, Nelson has collaborated on music with Wynton Marsalis, Paul Simon, Julio Iglesias, Bob Dylan and Ray Charles, among others. He also formed part of the Highwaymen, a supergroup where he played with Johnny Cash and Kristofferson.

In addition to several hits, Nelson added several concept albums to country music, although his first experiment was a sales failure. Jerry Wexler, a legend of the Atlantic label, convinced Nelson to follow his instincts. In 1974, he released Phases and Stages, which he recorded at the legendary Muscle Shoals, Alabama, studio. There was a simple idea behind the album: one side of the record took a woman’s view of a relationship and the other one depicted a man’s perspective. “But both were about sadness over a relationship in ruins,” says Nelson.

One of his most influential works came two years later. Red Headed Stranger (1975) is another concept album. The studios gave him $60,000 to record it, but Nelson got by on $2,000. The label executives hated it the first time they heard it. The title track, written for Perry Como without him ever singing it, was about a femicide committed by a Montana cowboy. Despite the executives, Nelson’s contract gave him the last word and the album hit stores with that song included. It became a bestseller and created a public alter ego for the red-haired, braided singer.

Nelson moved to Austin, a progressive oasis in a conservative bastion. Red Headed Stranger included Nelson’s first number one on the rock charts, Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain. He also found success with Troublemaker (1976), a gospel album. Stardust (1978), produced by Booker T. Jones, topped the charts with covers of classics by Duke Ellington, Irving Berlin, George Gershwin, Dorothy Fields and Johnny Nash.

In 2006, already an established and wealthy legend, Willie Nelson and his brother Bobby (who is also his pianist) gave a nod to their childhood faith. In 2006, they bought the church in the town of Abbott that they used to attend with their grandparents after learning it was going to be torn down. The church is still standing.

A representative of the outlaw current within country music — a subgenre that honors those who became independent from the predominant Nashville sound — Nelson didn’t need to reach old age to talk about death. He’s been doing that since the 1970s. In Goin’ Home, the song that closes Yesterday’s Wine (1971), a man attends his own funeral to find out what is being said about him. Fifty years later, Nelson contradicted himself and wrote I Don’t Go to Funerals, in which he turns his back on his youthful idea and talks about his curiosity of knowing whether he can play with his great friends in the afterlife. “I’m not morbid about death. I even hope to reunite with the spirits that have left us before. I take care of my body, but I also know that leaving my body can be a relief,” he says.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.