Myke Towers: ‘Myke Towers is my superhero uniform’

The Puerto Rican singer left college to focus on his music, and the bet paid off. Now, his name is synonymous with streaming milestones, successful collaborations and number one songs on all the charts

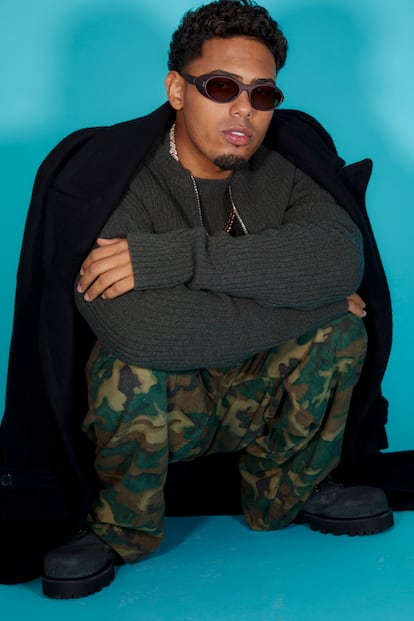

He arrives with black sunglasses, sneakers, pants and a white tank top with the letters MYT. A cloud of companions surrounds him. “This way, I feel in my habitat,” he confesses. The day we meet in Madrid, Myke Tower’s entourage includes seven men and one woman. “Some are childhood friends,” he says. “I know they are people who, if I stop doing this, will still be with me.” Beside him, one of his friends remains silent, unperturbed. He is used to the makeup artists, the photographers and the stylists that surround the Puerto Rican singer. “Goldo, play some salsa,” says Towers from the makeup chair. The friend takes his phone and a familiar Caribbean melody begins to flow from a speaker in the hands of another of his companions. Towers laughs. “You got primitive there, goldo,” he says. The song that plays is El cantante, by Puerto Rican singer Héctor Lavoe, released in 1978, which was so successful at the time that it earned the artist the nickname “Singer of Singers.” Primus inter pares. A title to which Towers is the legitimate heir.

The artist has the peculiar ability to turn almost every song he collaborates on into platinum; to accumulate songs with other singers of the moment such as Sebastián Yatra, Bad Bunny, Quevedo or — one of his idols — Daddy Yankee; to be liked, really liked, and to reach number one on every list that assigns numbers to music. He is also the one who created the soundtrack of the summer: Lala, the song by a Latin solo artist that has remained as Spotify’s global number one for the longest time, reaching the top just 11 days after its release.

Despite the record numbers and the fame, Towers appears withdrawn and careful from the moment the conversation starts. He does not make a false move. In his interviews, it is clear that he is not prone to making confessions or sharing private matters. There is Myke Towers and there is Michael Anthony Torres Monge — and they are not the same person. “I don’t like my family to call me Myke. Myke Towers is my superhero uniform. For the street, to go outside. At home I am Michael, and outside I wear my uniform,” he says.

Unlike other successful singers from his generation, Towers does not usually talk about his childhood. To him, there is not much to say. “I was a normal kid. I didn’t have many expensive things, I didn’t have luxuries, but I wasn’t poor, either. I am the product of the environment of Puerto Rico, my style, what I am. Puerto Rico made me.” Before becoming Myke Towers, Michael Torres was born and raised in San Juan, in the Quintana housing project. His parents were separated; he grew up with his mother, his sister, his little brother and his grandmother. It was her who instilled in him the love of music. “At home you could hear everything: salsa, merengue, bachata. I have cousins who like to sing. My grandma does, too,” he says. That music that was played then is the same that the singer returns to again and again in search of inspiration. “I don’t like to chase trends. To be a trend, you have to isolate yourself. Yes, I listen to the new things, but I listen to it once and that’s it. I like to discover people from other countries and go beyond Puerto Rico, but the old ones are always in the playlist,” he says.

At one point, the music that emanates from the speaker leaves the Caribbean and goes to the concrete of the American suburbs. Rap starts playing. Towers, who says that his influences range from Tego Calderón to 50 Cent, did not actually start his singing career with the reggaeton that made him famous. After finishing high school, he began a degree in business administration at the University of Puerto Rico; around that time, he started to spend more and more time with friends that made music. However, unlike them, he did not write or sing. “I didn’t want to sing. My thing was moving the music, the business,” he recalls. Perhaps it was those early days, helping others and learning how the industry worked, that helped him figure out the process by which a song becomes number one.

Spending time with other singers eventually motivated him to try his hand at recording something himself. He had never studied music (he says that he has only taken lessons to breathe and modulate his voice better); he was not even convinced that he really wanted to sing. “When I started to gain confidence, if they played something, I sang, and people started to motivate me, but you don’t do it until you decide to do it. It’s not easy. I didn’t dare. When I thought about singing, I was overwhelmed by insecurity. At first I was worried about what people might say, but then I stopped caring. I said: ‘If people like this, then I’m going to continue to improve.’ And that was what I set out to do,” he says. A star was born. “The way I see it, it had to happen. This is how it happened for me: it’s as if one day I was struck by lightning without realizing it and I had to prepare for that. Now I feel like I’m doing what I should. Before, I felt like I was doing the things that were going to lead me to that. Like a path. Like in a maze. Sometimes I felt like déjà vu and I thought: ‘Maybe this was meant to be,’” he confesses as he remembers those days.

At that time he was also working as a clerk at a sneaker store in San Juan. When his shift ended, he went straight to college. He used the little time he had left to make music. The feeling that he had found his way drove him to abandon college in his second year. “Maybe it’s a mistake, but I prefer to help my cousins who are studying. Thank God I was good at this, because I saw this way out and decided to get fully involved. I kept studying, but then I quit. Who knows if I will go back.”

He began to upload the songs he wrote and sang to SoundCloud. He wasn’t Myke yet; he was Mike, and most of the time not even that. He called himself Young King, a nickname he has stuck with and continues to use — today with a Z: Young Kingz — to refer to someone with integrity. From the internet, in 2016 Towers went on to debut with his first mixtape, El final del principio. After that came the big hits: Si se da, with Farruko; Dollar, with Becky G; Pareja del año, with Sebastián Yatra; Playa del inglés, with Quevedo; Ulala, with Daddy Yankee. Towers began to have something that all singers wanted — as well as 46 million monthly listeners on Spotify. “I don’t keep track of how my fame is growing, because the fame might be gone tomorrow. But I want to be financially well.” What does that mean for somebody who in 2016 sang about becoming a millionaire? “To have everything you need. Not just material things. Not having the stress of thinking about how I am going to get by tomorrow. I used to have it. Now there are many who want my privileged position, but you have to work hard for that.”

Fame does not seem to have caught the singer by surprise. In fact, when he talks about it, it is only to make it clear that theirs is not a romance; it is a marriage of convenience. “You can’t love fame. You can respect it.” Protective of his privacy, he does not show himself too much on social media. “I don’t like it very much. I’m a little old-fashioned, analog.” There are almost no photos of his partner online. It is known that they have been together since before Towers was world famous, that she lives in Puerto Rico and that together they have a three-year-old son named Shawn. The boy appeared in the video of the song Cuando me ven, from the album Lyke Mike, in which Towers returned to his roots of street rap. “That kid, if they let him, he sings. The little guy is moving very fast,” he says about him.

During the conversation, Towers has gradually gone from an initial nervousness that made him bite his lips to feeling more comfortable with the questions. His team is still hovering around. He interrupts the interview to ask for directions to a good spa in Madrid and to tell the stylist that he likes his sandals. He is tired because of the jet lag, but he does not want coffee (“I think that as a kid I drank too much as an act of rebellion, and now, ugh,” he confesses with an expression of disgust). He claims that the smoke from the stages spoils his voice and forces him to drink tea. For the photos he asks for natural makeup. When the questions are over and he stands in front of the camera, he relaxes completely. He takes control of the situation. He controls his expressions. His facial muscles respond to his commands only. He does not ask for advice. After a flurry of shots, he looks at the photos on the screen. “The first one is the good one,” he says.

–“You like to control everything.”

–“What I can, at least,” he says.

–“In your life?”

–“Whatever I can, as long as I can, I will to try to have control,” Towers adds.

–“Do you check everything?”

–“I try, yes.”

One of the peculiarities of Towers is that, while millions of people listen to his songs every day, he is practically unreachable. He has three phones. If you don’t find him on two of them, you probably won’t find him on the third. That one is just for the family — and sometimes, he confesses, he turns it off too. “You have to do right by yourself and then by the others. I’m not going to please everybody. Those who try, lose themselves. Thank God I haven’t reached that point of collapse. When I feel that way, I stop everything. That’s why my method is to get away from everything to clear my head, and then go back to work,” he says. For this, he often uses his country as a starting point. He says that Puerto Rico is the shore to which he always returns before heading out again. The same thing happens with his family, those he asks not to see him as a singer. “They are my motivation and I am their pride,” he declares.

After reaching number one on all the charts with the songs from his latest album, La vida es una, Towers contemplates other horizons. Maybe even Hollywood. “I would like to make movies. To be an actor or produce great films,” he says. However, he does not set dates; he just enjoys each day. “As Kobe Bryant used to say: ‘Game by game.’” Right now, the singer is going through a sweet moment. To use his own words, he is no longer a normal kid. “I thank God every day, even for the bad things. I feel grateful to life, to God, to my family. There are times when you don’t realize how much you have because you want more, but you have to be grateful for everything,” he says. Lo logré (I did it), the last song from La vida es una, is an ode to his achievements. The normal kid who grew up “misbehaving” in the streets of a Puerto Rican neighborhood, the singer who was afraid to sing, the artist who felt like he was struck by lightning. Michael, or Mike, or Young King, or Myke Towers; indeed, he did it.

PRODUCTION CREDITS

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.