‘The artist the world needs today’: The largest Rothko exhibition ever arrives in Paris

The Louis Vuitton Foundation has opened a major retrospective that pays attention to aspects that have been little explored in the painter’s work

In order to view a painting by Mark Rothko (1903-1970) following the painter’s instructions, first you must take two steps back from the canvas — or three, if you have small feet — and align yourself with the center of the work as if looking at yourself in a mirror. The artist advised standing 46 centimeters from his canvases to summon up the concentration necessary to understand his work, the immersion in the windows that each painting opened, that are always views of our internal abysses. There were other conditions: the works had to be hung almost at ground level, as in an artist’s workshop, and lit dimly so that it forced a sepulchral silence, like that which could be found inside a religious temple.

“He had strict codes, so to speak, because he wanted his art to be taken seriously and not as a commodity. For him, art was essential in the relationships between people,” says his son Christopher. “He didn’t want his paintings to be just commerce or a mere decorative object. He lived in fear that his works were just something pretty to hang over the couch,” he says, sitting at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris, which has just opened a colossal retrospective of the painter. The exhibition comes second of all time in the number of works exhibited, according to those in charge. In all, there are 115 paintings on loan from 36 public and private institutions from around the world, which shine in the cathedral-sized building that Frank Gehry erected a decade ago on the western edge of the French capital.

Its curators are Christopher Rothko, guarantor of his father’s legacy, and Suzanne Pagé, artistic director of the foundation created by the magnate Bernard Arnault, who is a great admirer of the painter. The businessman has one of Rothko’s works hanging in his office, but it will not form part of this exhibition because it is “in the process of restoration,” according to the museum. “Rothko is the artist the world needs today. There are few who have delved so deeply into the ‘fundamental human emotions’, as he called them. That is, tragedy, death, and ecstasy,” says Pagé. “The curious thing, in his case, is that he did it through a language of great sensuality. The more beautiful the work is, the more it disturbs us,” she adds. Duncan Phillips, one of his patrons, used to say that Rothko’s work generated “a feeling of well-being suddenly overshadowed by a cloud.” Or a sensory plenitude poisoned by a sting of melancholy. Each of his paintings, which aspire to “the same eloquence as poetry and music,” the artist said, reaffirms those words.

The exhibition covers the artist’s entire career, from his beginnings in figuration — with New York landscapes from the 1930s, full of emaciated bodies merging with the architecture, which seem like the work of a solitary and perplexed man, who observes the world from a distance — to the paintings in black tones that he painted before dying by suicide in 1970, through the famous large abstract formats for which he became a living legend. And it examines, above all, the lesser-known periods, including the supposedly minor ones. Unlike other retrospectives, the one that begins in Paris (running until April 2, 2024) features works from regional and university museums in the United States — from Nebraska to Arizona and from Toledo (Ohio) to Utica (New York) — which tend not to travel.

The Rothko family collection is well represented, through the best-known works of the so-called classical period — the large canvases of floating and blurred colors — but also other much less famous ones, which have almost never been seen in public. For example, Movie Palace (1934-35), exhibited only once in a New York gallery, depicts the interior of a cinema full of sad and deformed faces, among spots of color that seem to announce the abstraction of his later paintings, in maroon, gray, indigo, and brown tones.

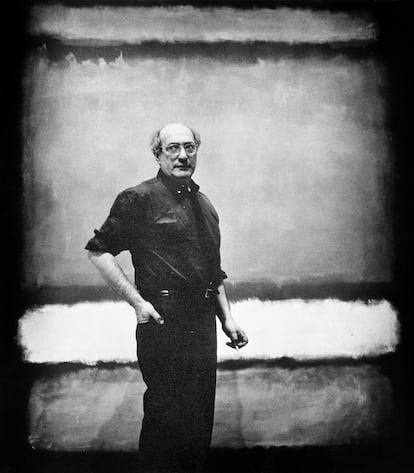

On the opposite wall, there is a portrait from 1936. Rothko paints himself as a sphinx, a monster from Greek mythology that posed unsolvable enigmas. “He hides his gaze behind dark glasses, his gesture is boring and inexpressive, and the background is neutral, as in a portrait by Rembrandt, whom he admired and whose works he used to go to see at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. It seems that he doesn’t want us to know anything about him,” remarks his son Christopher, who was seven years old when the painter died. Rothko hated biographical readings of his work and, starting in his forties, he dispensed with explanatory panels and also with titles, preferring to refer to his paintings with numbers or names of colors, thus erasing all possible clues for whoever admired them. “And yet, it is undeniable that he was a painter of his time,” says his son.

The exhibition is faithful to that idea: without fuss, it suggests that the mutations in his work respond to the murky context of the time. Rothko participated in the break with the human figure typical of his artistic generation (abstract expressionism) although he did not adopt the formal solutions of contemporaries such as Pollock or De Kooning. After Auschwitz, when poetry seemed obscene, he let himself be guided by the Nietzschean idea of transforming tragedy into beauty, by the internal light in the paintings of Turner or Vermeer, by the daring use of color in the works of Giotto. In 1946, he took a turn towards an abstraction that, in his own words, “lives and breathes.” These works are full of spots of color that tend towards regular geometry, until they become horizontal rectangles with diffuse edges that overlap in an impossible game of transparencies, which he achieves by using the tempera paints typical of the medieval tradition.

Rothko was also a figure of dissent in the art world. He was always fighting with critics, the market and collectors. Despite becoming rich, he had a problematic relationship with money and success. He abandoned the commission for the Seagram Building murals, in which he aspired to emulate Fra Angelico’s Florentine refectories, before understanding that the place was going to be a refuge for the New York bourgeoisie. He gave nine of these paintings to the Tate in London, which has lent them in their entirety for the first time for this exhibition. Having a sanctuary tailored to his needs was his dream. He achieved this by commissioning the Menil collection in Houston, where he erected an octagonal chapel in the sixties, when he was already a guest star at Kennedy’s inauguration and MoMA was dedicating its first retrospective dedicated to a living artist to him. He also gave up a project for the UNESCO headquarters in Paris, in which he planned to combine his work with that of Giacometti. With poetic license, the Louis Vuitton Foundation has tried to evoke it in one of the rooms of the exhibition.

Above all, the work of Marcus Rothkowitz (his real name) is the work of an artist who did not assimilate into his host culture, in which he never felt completely at home, as his son implies. “He was an eternal exile, an inconsolable guy,” Pagé confirms. Born in 1903 in the Russian city of Dvinsk, in present-day Latvia, he emigrated to the New World with his family at the age of 10, fleeing the pogroms. He hated religion ever since his mother forced him to pray the kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead, for an entire year. But in his work the imprint of his parents’ culture, the Jewish concept of the mitzvah (the kind act intended to cure the world’s ills), and the trauma of witnessing the Holocaust from a distance.

“He was not a religious man, but he was aware of his Jewish heritage,” says his son. “In his time, the world falls apart and people experience atrocities that threaten to end humanity. But, even in the midst of these horrors, his painting remains a positive act. Every time he painted a painting, he did so convinced that art had transformative powers, and was able to move the soul and thus restore relationships that have been fractured.” And as we said at the beginning: Rothko is the artist the world needs today.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.