The great families of the history of art: Is talent hereditary?

From Gentileschi to Roldán and Sorolla, the passion for painting, sculpture and design has been passed from fathers to sons and daughters

Many visitors to museums and art galleries find themselves surprised by the family ties between many of the artists exhibited. During the opening of the retrospective that Madrid’s Prado Museum has dedicated to Francisco de Herrera el Mozo, curator Benito Navarrete took the opportunity to talk about Herrera el Viejo, a remarkable artist who had a devilish relationship with his son. At the same event, the museum’s deputy director, Andres Ubeda, tried to memorize the names of the artists with family ties who are represented in the museum. In general, they are fathers and sons or daughters: Lucas Cranach the Elder and Lucas Cranach the Younger; Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi; Pedro Roldán and his daughter Luisa Ignacia Roldán, La Roldana; Mariano Fortuny Madrazo, son of the painter of the same name and grandson, on his mother’s side, of Federico Madrazo, and Joaquín Sorolla and his daughter, the sculptor Helena Sorolla, among many others.

Among art world experts it is considered an indisputable certainty that there is no gene by which artistic talent is inherited. Paloma Alarcó, head of the Modern Painting Conservation Department at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, states categorically that she does not believe in the existence of an artistic gene. The transmission of knowledge that the artist can instill in those around them, whether they are relatives or not, is another matter.

That mastery of which Alarcó speaks is present in many other professions linked to culture. For example, actors in the 16th century could only be trained in guilds, which were always monopolized by the families of performers. In theory, access to these schools was free, but in practice the key was provided by the family name. In painting or sculpture, the teaching took place in academies, or the artists themselves shared their knowledge in exchange for work in their workshops. One of the most famous cases is that of Jorge Manuel Theotocópuli, the son of El Greco, who absorbed the essence of the craft by his father’s side in Toledo.

Another traditional case is represented by Pablo Picasso. His father, José Ruiz y Blasco, a drawing teacher and painter, poured all his knowledge into his son from a very early age. Picasso always displayed gratitude towards his father, although on one occasion he described him as a “painter of dining rooms,” due to the ornamental simplicity of his canvases. However, none of Picasso’s descendants have dedicated themselves to art, with the exception of Paloma Picasso’s jewelry design.

The Gentileschi

But for whatever reason, numerous families have provided the backbone of the history of art. For example, the Gentileschi. Orazio Gentileschi (1563-1639) was the son of a Florentine goldsmith who found success in Rome, where he raised a family that was broken when his wife died. The eldest of his four children was Artemisia, a girl to whom the fate of those times prescribed a convent in which to spend her life. But her father’s understanding character made it possible for Artemisia to work and learn the trade in the paternal workshop, located next to the family home, allowing her to come and go without being seen in a society that did not tolerate women leaving the home. Her selflessness, talent and courage led to her work being applauded, first under the protective signature of her father. Later, patrons’ commissions required her authorship. Artemisia’s life story is well known. Although she was traumatized after being raped by one of the apprentices at the workshop marked her, she survived and did not stop until her attacker was brought to justice.

The Roldáns

Luisa Ignacia Roldán Villavicencio was born in Seville in 1652, daughter of the sculptor Pedro Roldán. Her father, observing the inclination towards sculpture that the girl displayed as a child, taught her to draw and model. Roldán’s workshop was a real family business. Four of his sons, three sons-in-law and a nephew worked there. Luisa was entrusted with tasks such as gilding the figures, but without waiting for instruction she began to design and sculpt by handling saws, hammers, and pointers. A brilliant student, she soon mastered the techniques of working in wood or stone. As in other cases, what came out of the workshop was considered the work of her father of the family, Pedro Roldán. But as time went by, Luisa Roldán imposed her knowledge and criteria until she became one of the most notable artists of the Spanish Baroque period.

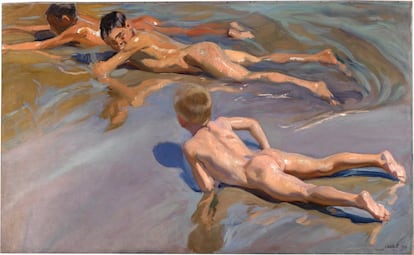

The Sorollas

Helena Sorolla was the youngest of Joaquín Sorolla and Clotilde García’s three children. Born in Valencia in 1895, she was a modern and free-thinking woman, trained in the Institución Libre de Enseñanza (Free Institution of Education). Her siblings, María and Joaquín, dedicated themselves to landscape painting, a difficult genre to live up to given their father’s prolific output. However, Helena chose to concentrate on sculpture, an activity that she combined with her dedication to her family. In 2014, a retrospective of her work was exhibited in Valencia. Critics regretted that she abandoned her vocation too soon to devote herself to the family, although sometimes the weight of a great star, such as Joaquín Sorolla, requires too much space for his own creative impulses.

The Fortunys

Mariano Fortuny Madrazo (1871-1949) was the son of the painter of the same name and a grandson, on his mother’s side, of Federico Madrazo, painter and a former director of the Prado. With such a glittering family line, Fortuny understood art as a whole, in which all disciplines were equally important. In an anthological exhibition held in his native Granada in 2021, it was recalled that as a designer he had Orson Welles wear his costumes in Othello and Charles Chaplin bought more than 30 dresses from him. Passionate about technology, he invented a system of indirect theatrical lighting that was radically innovative at the time. He also designed a dress, the Delphos, in which Lauren Bacall received her Oscar in 1979. Meanwhile, he also painted constantly. At the age of 18, he settled in Venice and it was there that he achieved worldwide fame, as reflected in the Palazzo Fortuny Museum, one of the most beautiful in the world.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.