From Beyoncé to ‘Black Panther’: Why has Afrofuturism become such a popular cultural movement in the United States?

The Smithsonian enshrines the trend, which blends science fiction and racial consciousness and is conquering film, pop music and museums

A specter is haunting the United States, the specter of Afrofuturism. It is featured in museum programs across the country, inspires pop stars like Beyoncé and Janelle Monáe, encourages revisiting Black women science-fiction authors and even has its own blockbuster movie, the two installments of the fantasy Black Panther. Both served as the Trojan horse for introducing into mainstream cultural discourse a term that critic Mark Dery coined in 1994 from the fringes of academia. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines Afrofuturism as “a movement that uses the framework of science fiction and fantasy to reimagine the history of the African diaspora and to set forth a vision of a technically advanced and hopeful future for Black people.”

Past, present and future are cited right in the title of the exhibit Afrofuturism: A History of Black Futures, at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in Washington, D.C. This exhibit joins two others that are currently on view: one at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which is a permanent space that imagines a 19th-century room through the lens of an examination of present-day racism, and another in artist Lauren Halsey’s pharaonic-inspired monument, which is installed on the Central Park building’s roof. But the Washington initiative goes one step further in the acceptance of Afrofuturist ideas: part of the Smithsonian, the NMAAHC occupies a prominent place on the National Mall, a symbolic battlefield for the discourse with which the United States tells its own history.

The semi-permanent exhibition, co-curated by Kevin M. Strait, the institution’s curator, was conceived even before the museum opened its doors in front of the White House in 2016. “These ideas were born in African societies, traveled to the United States aboard slave ships, and now emerge in our contemporary culture,” Strait explains in a video interview. “I like to think about Afrofuturism in a number of ways. I think it’s an aesthetic. It’s part of a cultural movement. It’s a multimedia genre, all of which focuses on gaining empowered futures and liberated spaces for African Americans. I think it’s a way that African Americans have engaged with the past and the present to think about the future. I think if an alien came from outer space, I would explain the long history of America and its race relations so that there’s more of a context to understand the need to have a name for this type of expression.”

Strait jokes that most likely this alien would have already learned about Afrofuturism, because before arriving on Earth he would have had contact with the jazz pianist, poet and cosmic thinker Sun Ra (1914–1993), who claimed he came from Saturn as an escape from the reality of having been born in Birmingham, Alabama, during the Jim Crow era’s reign of racist terror. Ra, the author of an inexhaustible body of work, is considered the father of Afrofuturism. The influence of his ideas, which combine a fascination with Ancient Egypt and the space age, has only continued to grow in the 30 years since his death.

Funkadelic’s Mothership

“[Afrofuturism] is a pattern of escapism, [which] I think is an effective escapism, this sense of understanding your reality beyond the limitations of what and how it’s been explained to you previously,” African American artist Rashid Johnson recently told EL PAÍS. “People look toward Afrofuturism as a way to negotiate the terms and the complexity of the current condition of Blackness in this country and in the world. To imagine an opportunity for it to change and evolve and look different in the future. And to capitalize on a sense of creativity and improvisation, and a sense of self that is ever evolving and growing and changing,” he says. “The ideas that I lay out are far from the only chances that we have to imagine what Afrofuturism is, you can break down the terms really independently, and think about African-ness as different from Americanness… how Africans evolved and moved from the continent of Africa to America and what happened to them in that journey, to think about what would potentially happen to us if we were to even journey further, if this became an interplanetary discourse,” he adds. “How would our understandings of self evolve and change?”

That sidereal analogy for describing the African diaspora already appeared in the essay in which Dery coined the concept. “African Americans are, in a very real sense, descendants of abducted beings,” the cultural critic wrote. Perhaps that’s why a spacecraft is the central artifact of the Washington exhibit.

In 2011, the Smithsonian purchased a replica of the mothership that Parliament and Funkadelic used in their 1970s concerts from the bands’ leader, George Clinton, Black music’s unparalleled figurehead. According to University of California, Los Angeles, professor Tiffany Barber, space is a key concept in Afrofuturism. “To upend how the traumas of slavery, colonialism, and imperialism continue to organize our sociopolitical present and future, Black makers and thinkers have long looked to space — outer space, inner space, cyberspace — for room to grow, for more amenable geographies and species, and for places to hide and flourish,” she explains.

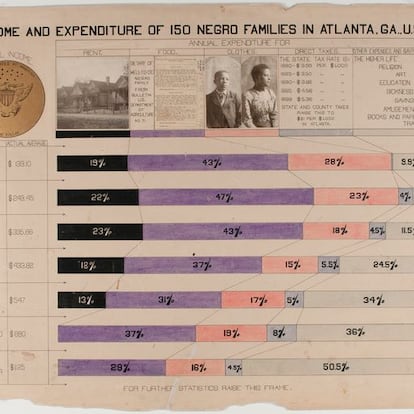

There are abundant examples of that in the museum. As Smithsonian exhibitions always do, this exhibit tells the story of Afrofuturism through objects: from the infographics shown at the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition, with which W. E. B. Du Bois wanted to explain to the world the institutionalized racism in the United States at the time, to the typewriter of science fiction novelist Octavia Butler (1947–2016), whose best-known work, Kindred, was recently adapted for television. The exhibit also features Black characters from DC and Marvel Comics and the costumes of two audiovisual icons: the one worn in Star Trek by actress Nichelle Nichols, who died in 2022, and the one worn by Chadwick Boseman in the first Black Panther film, before the actor’s untimely death.

Music occupies a special place in this journey: in addition to legends like Ra, Clinton and Prince, the exhibit includes musicians from rock (the guitar and pedalboard of Living Colour’s Vernon Reid), rap (from Outkast to Rammellzee) and soul (Labelle and Erykah Badu).

There are also references to some of the events that have shaped recent U.S. history — and activated the Black Lives Matter movement — such as the 2014 anti-racist riots in Ferguson, Missouri, and the protests against statues glorifying the Confederate past in Richmond (Virginia) in 2020, in response to the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor (present in the exhibit in a large-format painting), as well as the unpunished murder of Trayvon Martin in 2012.

Martin is remembered with the flight suit he wore at a camp for future aviators, which he attended as a child. The choice of that artifact for the Smithsonian collection — worn at a happy moment in the boy’s life, which was tragically cut short at the age of 17 — reflects another essential concept of the discussion of race in the United States: Black joy as an act of resistance, especially by women, in a society where the African American experience is usually dehumanized, from the sadism of slavery to the news networks’ repeated broadcast of recurring acts of police brutality. “Afrofuturism is about imagination, and the freedom that comes with thinking about other worlds, regardless of the dangers of white supremacism,” Strait explains.

In the catalog, speculative science fiction writer N. K. Jemisin, author of the Broken Earth series, expounds on this idea: “Oppression makes the strangest things radical. Imagination, for example (…) This suppression of imagination takes many forms and occurs in many contexts. It looks like pop culture that primarily depicts Black characters in ways that justify the status quo, as criminal ‘thugs,’ for example, or menial laborers, or prostitutes; as people who are innately immoral and unintelligent; as people who need to be controlled for their own good. This is the context that gave rise to Afrofuturism — an art form, a movement built to joyously break these pop-culture chains. Black people flying spaceships! Shooting laser pistols, wielding lightsabers! Black people still existing and thriving for the benefit of no one but themselves, in a glorious future!”

According to Jemisin, Afrofuturism is “just plain fun, but just by existing, Afrofuturism threatens America’s status quo.” And this time it does so from the very heart of the system, right in front of the White House.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.