Everything the Romanian secret police knew about Nadia Comaneci

A book made from Securitate reports reveals how the Ceausescu dictatorship spied on and controlled the most iconic gymnast of the 20th century from her first successes to her escape from the country

When the iconic gymnast Nadia Comaneci clandestinely left Romania in November 1989, Stejarel Olaru was a 17-year-old teenager who was already planning his own escape from the regime that Nicolae Ceausescu had led since the 1970s. However, he had little time to execute his plan, because just a month after the athlete’s escape the fall of the communist dictatorship was imminent. The Christmas Revolution — originating from the dictator’s order to shoot at the civilian population demonstrating in the city of Timisoara — broke out and on December 25, Ceausescu and his wife Elena were shot.

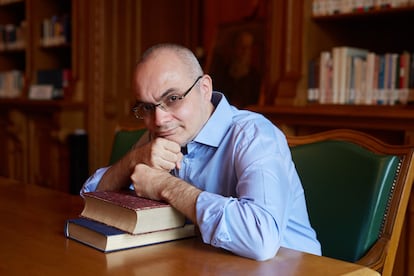

Now a historian, political scientist, and writer, Olaru studied the history of his country’s intelligence services in depth, especially the Securitate (the secret police during the communist regime). In 2020 he wrote Nadia Comaneci and the Secret Police: A Cold War Escape, published by Bloomsbury. The book, published earlier this year, meticulously collects all the reports from the Securitate and people close to the gymnast until her departure from Romania, and sheds light on little-known parts of her life, especially her tumultuous relationship with her coach, Bela Karolyi, who subjected his athletes to a regime of terror involving physical and psychological abuse.

Behind the Iron Curtain, Romania was, along with East Germany, one of the countries that suffered the most from the rigidity of the secret police. Olaru’s book reflects this level of extreme surveillance, as most of the testimonies in the book are reports transcribed by that body. It was very normal to tap phones and install microphones in private residences, in addition to mobilizing people to spy on others. For example, when Nadia escaped, her mother, brother and sister-in-law got together to discuss what strategy to follow during the interrogations, and since they were aware that there were microphones in their homes, they played a classical music record at full volume so that they would not pick up their words.

It is still not known exactly how large the Securitate’s network of informants was, because the documents with this data were destroyed shortly before the revolution. Some experts estimate that there were 1.5 million informants, while others place the figure at 400,000 — in a population of 22 million people it would represent 6.8% or 1.8% of the inhabitants. In fact, most of the people in the gymnast’s environment, from coaches to teammates, to facility employees and members of the national sports consulate, were or had been informants at some time.

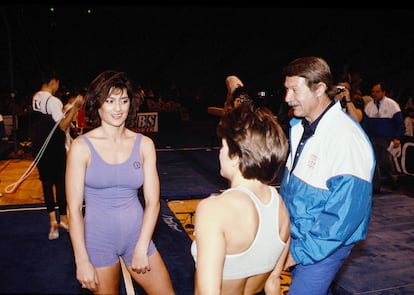

The book includes the increase in reports with the arrival of Bela Karolyi and his wife, Marta, to the Onesti gymnastics team, at which time Comaneci began to stand out. The more success Romanian gymnasts achieved in major competitions — culminating with Comaneci’s perfect 10 at the 1976 Montreal Olympics at just 14 years old — the more people and resources the Securitate mobilized to find out what the training and procedures were really like. Olaru goes into detail on the fight between Nadia Comaneci and Bela Karolyi. The book contains a multitude of testimonies that describe how Karolyi punished the girls’ mistakes with beatings and forced them to train and compete even if they were sick, and to ignore injuries and the instructions of sports doctors.

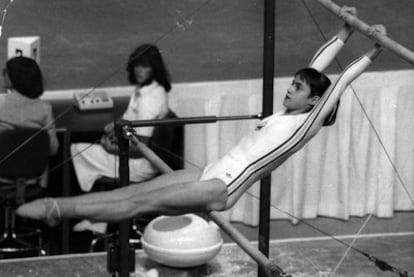

They were also constantly humiliated because of their weight. In an interview that Nadia gave with her teammate, Teodora Ungureanu, in December 1977 and that was recorded by microphones hidden in her house, the two mention the insults that Nadia received from her coach for having gained 300 grams: “He called her fat, he said she was like a widow with 15 children, a drunken goose. Tummy rolls, love handles.”

Olaru describes the Karolyis’ obsession with the athletes’ bodies, as they forbade them to eat what they wanted and weighed them every day. If they gained weight, they were put on strict diets for days without eating or drinking water, in addition to being forced to attend sauna and running sessions. One of the reports that reveal the cruelty of the coaches on this issue came from the team’s choreographer, Geza Pozsar, a regular informant whose code name was Nelu, who wrote: “Bela is a sadist, because at the table, right in the presence of hungry girls, he eats without a care.”

Although the Securitate and the party leadership were aware of these abuses, no one ordered that the Karolyi couple’s methods be changed, since they continued to win medals for Romania, which competed in gymnastics against its biggest rival, the USSR. Only Comaneci and Ungureanu managed to get the Romanian gymnastics federation to change their coaches in December 1977, but they did not last long, since the young women, who were entering adolescence, were difficult to control.

To this day, Comaneci’s complicated relationship of dependence and hostility with Karolyi remains an unsolved mystery, since she, unlike other gymnasts, never reported the treatment she received from him. She did not break her silence even after fleeing to the United States, the country that Karolyi had defected to in 1981. She has even collaborated with him on several U.S. projects related to sports.

Olaru consulted the medalist, who is currently 61 years old and lives in the United States, to correct any inconsistencies in his book, although she warned him that she would decline any interview on the matter, because she considered that part of her story was closed. Nor did the historian decide to include anything about her numerous romantic relationships, recorded in many Securitate reports: “I analyzed all those documents, but I found that none of them contained any politics. In my opinion, that belongs to Nadia’s private life, and I was not in the place to write about this, nor did I consider it relevant. Of course, many of her boyfriends were important and famous people in Romania at that time.”

However, the gymnast’s supposedly most significant romantic relationship was the one she had with the dictator’s son, Nicu Ceausescu. In the book, Olaru shows how his mother, Elena Ceausescu, was the one who prevented her from traveling to Western countries and who little by little restricted her departure from the country.

–Why didn’t you talk about her relationship with Nicu Ceausescu in the book? This did impact her private life, because it directly affected the control that the Securitate exercised over it.

–I know little about her relationship with him. I only have some testimonies from people who were close to her during those years. I asked her if this relationship had been real, and she denied it. She said they only had a working relationship. But, above all, I did not include any of this because there was no trace of the relationship in the archives either, because the Securitate was not authorized to write anything about the dictator’s family.

–Did they know in Romania that Nadia Comaneci’s life was so complicated?

–Not at all, we didn’t know anything. We were all very surprised when she left. We said, ‘My God, even Nadia left.’ We believed she was a privileged person. It was a sign for us that the end of the regime was near. I also wanted this book to be more than a biography. I wanted to show how difficult it was to be an excellent athlete in a communist country, how political her life was and how difficult it was to become a champion at that time. It was another world.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.