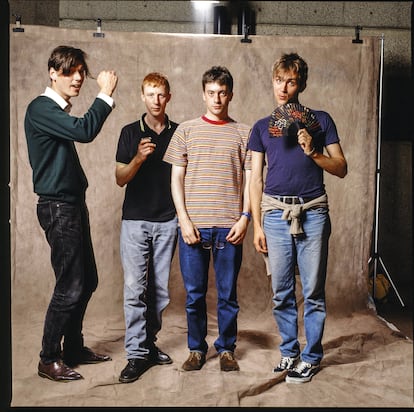

Blur: ‘We’re not AC/DC. We’ve never been basic. We play too many chords to be basic’

The rock band — which redefined British music in the 1990s — has a new album and tour. They confirm that if there’s something they handle even better than the melodies, it’s the changing times we’re living in

—“How’s it going?”

—“What, exactly?” Damon Albarn, 55, answers his first question from EL PAÍS with a touch of detachment. He has phlegm in his British accent, which gives him the gravitas of a Roman emperor.

A few minutes before the interview, his publicist drops by to tell us that Albarn isn’t in a good mood. We’re set to meet him on the terrace of a seaside Barcelona hotel, just a few hours before his concert at the Primavera Sound Music Festival.

“There are more and more tourists here. It’s difficult to find the authentic city that I discovered in 1988,” Albarn sighs. One recalls how he criticized Adele when she attempted to collaborate with him on some songs. She told Rolling Stone that their encounter “ended up being one of those ‘don’t meet your idol’ moments.”

Graham Coxon —another creative soul from Blur — joins the interview. He isn’t at the height of likability, either, but compared to Albarn, he’s a cross between Mother Teresa and a UN blue helmet.

Albarn and Coxon met as schoolchildren in Colchester, East London. “Recently, we had the romantic idea of going back there, to connect with our past. But there was nothing left — they had built a new building. It was quite strange,” they note. Since they reconciled in 2009, the group has recorded two albums: The Magic Whip (2015) — a murky album that they recorded in Hong Kong — and their latest work, The Ballad of Darren, which will be released on July 21.

As we listen to the songs about a dozen times before the meeting, the album sounds like the opposite of the previous one. It’s a return to the crystalline melodies, the riffs of the band’s glory days, and the mischievous and witty lyrics, as if they’ve woken up after a cryogenic period. In short, the songs are like a return home for Blur. “We never really left,” Albarn replies. “There always has to be a good reason to get back to playing [music] with people you’ve known since your teens. We’re not just people playing music, because there are expectations, [people have] the memory of your previous songs. For me, the reason is always to make good music again. That’s the trick.”

The record ends the long period in which Albarn seemed most enthusiastic about Gorillaz, his excellent solo records, his Cantonese Chinese musicals, his collaborations with African artists, or his rock operas about 16th-century English mathematicians. After all of this, the reunion of Blur seemed unlikely, but unlike other veteran bands that try to take advantage of nostalgia for their work, the reunited members don’t seem to be guided by cynicism.

“Of course not. Our aim is the present. I guess tonight we’ll see if we’re still modern,” Albarn chuckles defiantly. The answer ends up being a resounding yes (even though he continues to wear the same sweatshirts as in the 1990s). The best part of the concert is the final bit, with a long succession of perfect hits from the height of the band’s fame. When they close with The Universal — one of their classics — some of the bandmates shed tears.

We can see the album as getting back to basics, to the essentials — to what defined the group when it formed more than 35 years ago. “Yes, exactly. That was exactly what we wanted to do,” Albarn says enthusiastically, in his only energetic moment during the interview. But then, he changes his mind, taking issue with the word “basic.”

“Actually, that basic thing sounded a bit dry to me. We’re not AC/DC,” he protests. “We’ve never been basic,” Coxon seconds. “We play too many chords to be basic.”

When asked to define the record with one word, Albarn chooses “aftershock.” That is to say, the aftershock of an earthquake — the tremor that comes after the roar caused by a bigger one. “So many things have happened over the years. Since our last album, we’ve lived through Brexit, a pandemic and the war scenario in Europe. As Mao said about the French Revolution, it’s too early to judge the effects it will have,” Albarn notes. (According to a quick check, it was actually Mao’s prime minister, Zhou Enlai, who said this in reference to the protests that gripped France in May 1968, but it wouldn’t occur to us to correct him.)

Their lyrics seem to reflect a state of perplexity and disorientation. “Yeah. After all, we’re called Blur,” Albarn shrugs.

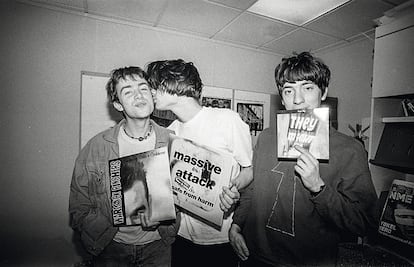

Blur became famous in the early years of Blairism, when the Thatcher era had come to an end. We ask the frontman: is being British rather uncool these days? “Clearly, it’s not ideal,” Albarn sighs. “Politics is stagnant and polarized. We should have coalitions, like almost everywhere else, but it’s impossible.” When asked if he regrets the political use of his alleged proximity to the Labor Party, after he agreed to meet with Tony Blair shortly before he won the 1997 elections, he dodges. “Our music was never a celebration of England,” he replies. “We didn’t operate within those parameters. We were English, but more at street level,” Coxon adds. “We were satirical, we used our country as a theme, but not like that. We never really did ‘Britpop.’ We’re not part of that.”

But wasn’t that wave of British culture the main reason for Blur’s worldwide success? “We were already successful before,” Albarn affirms. “They [other bands and studios] used us, they appropriated our music.”

For the cover of their album, they’ve chosen an image by Martin Parr: a typically British public swimming pool, built right next to the sea, under a cloudy sky. “In [Parr’s] work, there’s melancholy, sarcasm and ridicule,” Albarn lists. Clearly, they have something in common.

Years ago, Coxon said that the Blur members had stopped being friends. “Now, we’re partners,” he clarifies. Hasn’t he changed his mind? “I don’t know if it was fair to say that… maybe I didn’t phrase it well. We know what our relationship is like and we don’t need to give anyone explanations. We started making music together and we continue to do so. In any case, this has been one of my longest-lasting relationships, and there have only been two or three.” Albarn chimes in to settle the matter: “To play music with other people, you have to be able to get into their skin.”

They know they’re survivors by now: there’s hardly anyone left from their musical era, in a time when popular music increasingly talks about “going to the club, getting drunk in the club, and then leaving the club,” as Albarn describes. What’s Blur’s secret? “Take frequent breaks. The [1990s] were so intense. We understood that this would be the only way to sustain it,” Coxon answers, with a knowing look at his old nemesis.

In tough times, it’s best to close ranks with those who are most similar to us. Even Noel Gallagher has apologized for wishing that the Blur members — at the height of their rivalry with his band, Oasis — would be infected with AIDS. “I obviously don’t wish that. A bad cold, I should have said. Flu maybe?” he joked.

The agreed-upon 30 minutes has passed. The last question will be whether they feel influential. “Fuck yeah,” Coxon replies in a split second. Beside him, Albarn takes a while longer. “We must be, if we’re still here.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.