Jane Birkin, the ‘pin-up without curves’ who conquered auteur film

In the wake of May 1968, France embraced the smiling British actress with open arms. She began her career starring in lighthearted comedies and went on to work with Godard, Rivette, Tavernier and Agnès Varda

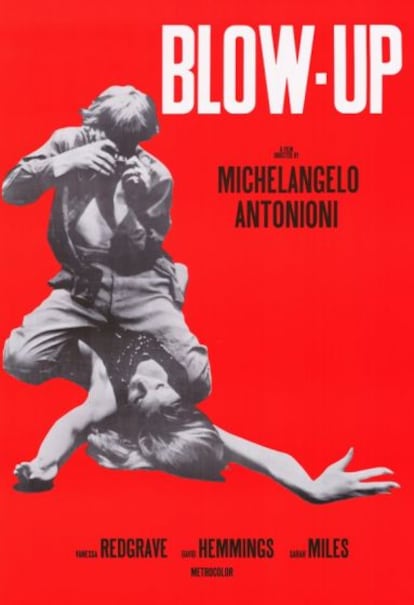

Jane Birkin was an actress before she was a singer. When in 1969 she scandalized half the world with her musical orgasm with Serge Gainsbourg, the French-British interpreter, who died on Sunday in Paris, was already enjoying an incipient career in cinema. Despite her upbringing amid the gentry of the London neighborhood of Marylebone, she had participated in two films with the sexual revolution as a backdrop. She played a marginal character in The Knack... and How to Get It (1965), by Richard Lester, and in Michaelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-up (1966), she played an aspiring model in the famous threesome scene, which provoked the first of a series of controversies in her career.

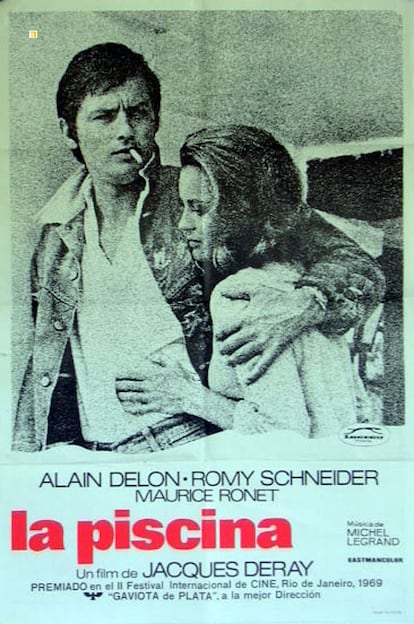

There were plenty of girls like her in Swinging London. “I was just lucky enough to get to Paris first,” she said. France knocked on her door in 1968, when director Pierre Grimblat was looking for a young English woman to play the lover of a married filmmaker in the film Slogan. Her co-star was none other than Gainsbourg, with whom she began a relationship that would last 12 years. Her debut was followed by The Swimming Pool (1969), by Jacques Deray, which observed the games of seduction (and destruction) between three adults, including Alain Delon and Romy Schneider. Throughout the 1970s, Birkin became a playful transgression, a smiling offense, within a nation “widowed by De Gaulle,” as Pompidou would say, which got over the hangover from May 1968 and embarked on the path towards Giscardian neoliberalism.

Birkin had no special talent, except for embodying modernity, similarly to other New Wave actresses like Jean Seberg and Anna Karina, also androgynous foreigners. “You’re half boy,” Birkin was told by her classmates at the Isle of Wight boarding school where her parents, a Royal Navy admiral and actress Judy Campbell, sent her to study. In this context, Birkin played the role of a “ravissante idiote,” in her own words: a brainless but charming girl, in popular comedies that were great successes, such as I’m Losing My Temper (1974), directed by Claude Zidi, known for his collaborations with Louis de Funès. Birkin had an alien presence. She filled her films with a delicate strangeness, a grim melancholy, with her inimitable whistle voice and a fragility that she brandished with force. “I am a pretty tough woman. The fragile one was Gainsbourg,” she told EL PAÍS in a 2017 interview.

In her film career, eclectic like few others, she was guided by curiosity, by primal desire, without any career strategy. She tried her luck with Roger Vadim in a failed lesbian Don Juan with Brigitte Bardot in 1973, and then with Je t’aime moi non plus (1976), directed by Gainsbourg, where she played a waitress who fell in love with a gay trucker, the Warholian Joe Dallesandro. A small role followed in Death on the Nile (1978), alongside Bette Davis, Mia Farrow and Maggie Smith, one of her few forays into commercial English-language cinema.

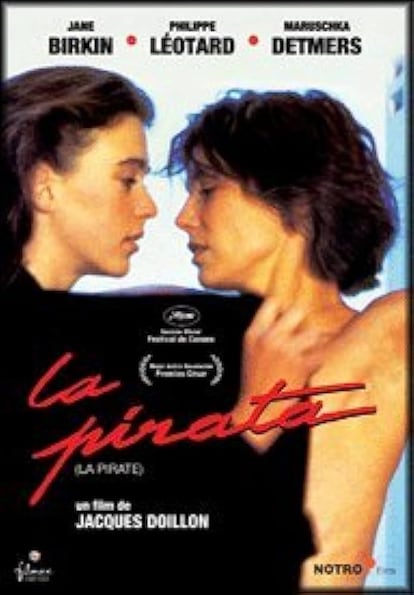

Her transition to French auteur cinema took place in the 1980s, after she met Jacques Doillon, for whom she ended up leaving Gainsbourg. The director detected dramatic potential in the sexual icon who appeared naked in Lui, a monument to the erotic press. He wanted to “button her up to the neck” to force her explore other registers. It happened in The Prodigal Daughter (1981), the Bergmanian encounter between a woman and her abusive father, in The Pirate (1984), massacred by the press at Cannes, and in Comedy (1987), their last film together before their separation.

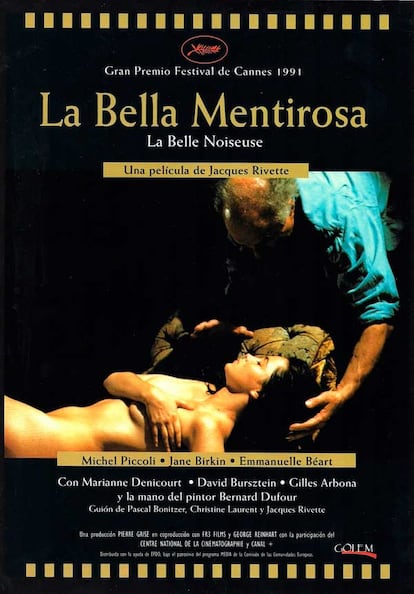

Transformed into a prestigious actress, she earned the respect of the greatest filmmakers. She shot the Dostoevsky-inspired fable Keep Your Right Up (1987) with Jean-Luc Godard; the fantasy documentary Jane B. by Agnès V. (1988) with Agnès Varda; Daddy Nostalgie (1990), another father-son story directed by Bertrand Tavernier, and The Beautiful Troublemaker (1991) with Jacques Rivette, as the wife of a Picassian painter. The theater also knocked on her door: Patrice Chéreau had her play Marivaux in the 1980s. Twenty years later, she appeared in Electra in Paris and as Queen Gertrude of Hamlet in the United Kingdom. Her only theatrically released feature film as a director, the autofiction Boxes (2006), depicted her family life. Her alter ego was played by Geraldine Chaplin, and her youngest daughter a very young Adèle Exarchopoulos.

Birkin began as a pin-up without curves, as she herself said, but ended up becoming an actress endowed with a certain authorship. She joined that select club of actors who are always recognizable under the mask: the person and the character become interchangeable, as happened to Catherine Deneuve, Isabelle Huppert and Juliette Binoche. Birkin was the star of a sensational “sad comedy,” a term of her own making. Patron Saint of foreigners residing in France, of those voluntary exiles who submit to a complete assimilation — the only one allowed in the host country — she was known for her particular way of using French, with an immutable accent despite having been in the country for more than five decades. She misconjugated her adopted language, she chose the wrong articles and abundant expressions in disuse, to the point of making us wonder whether she did it on purpose to be likeable. The writer Olivier Rolin, who was also her partner, used to call it “the Birkin Creole language.”

Her legacy in the cinema will be Jane by Charlotte (2021), a documentary directed by her daughter, Charlotte Gainsbourg, a profound dialogue between a mother and daughter separated by a strange modesty. Weakened by her health ailments, but still strong enough to work in her garden, the film found a Birkin resting at her home in Brittany’s Finistere, opposite the beach where her father spent the end of World War II rescuing allied soldiers. She also visits the house in the Parisian neighborhood of Saint-Germain where she lived with Gainsbourg, on the mythical Rue de Verneuil, for the first time in 30 years. “It looks like Pompeii,” Birkin exclaims in the documentary. Charlotte keeps that dark-walled dwelling just as her father left it. And she plans to open it to the public as a house-museum before the end of the year. This mausoleum for Gainsbourg will now also have a bit of a Birkin.

Jane Birkin in seven movies

'Blow-Up' (1966)

'The Swimming Pool' (1969).

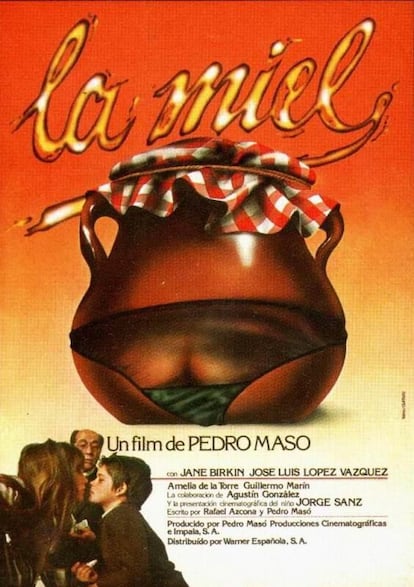

“Honey’ (1979)

‘The Beautiful Troublemaker’ (1991).

'The Pirate' (1984)

‘I Love You, I Don’t’ (1976).

'Jane by Charlotte' (2021).

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.