‘Which of these women would you sleep with?’ How ‘Flashdance’ ended up influencing everything we watch

Forty years after its release, the musical film about a welder who moonlights as a dancer in a club has left an aesthetic legacy in everything from fashion to what we watch on Netflix

To help decide who would play Alex in Flashdance, Paramount director Michael Eisner gathered 200 production company workers, projected images of actresses Leslie Wing, Demi Moore and Jennifer Beals, and asked, “Which of these women would you fuck?” That’s the story the film’s screenwriter, Joe Eszterhas, tells in his memoir Hollywood Animal. A tamer version says the images were shown to a group of women who were asked: “Who would you like to be your friend?” If one knows anything about Hollywood, it is easy to decide which story seems more credible. In any event, 18-year-old Yale student Jennifer Beals was the answer to the question, and she was chosen to play Alex Owens, the most famous welder in movie history.

Beals hesitated before accepting the role, as did everyone else who was involved in a project that had been shelved for two years. She didn’t have much faith in its success. Brian de Palma and David Cronenberg had refused to direct the movie, and the film’s eventual director, Adrian Lyne, had turned it down several times: “When I first read the script, I thought it was a bit daft, really. But in the end, it’s a fairy tale. I think that’s why it appealed to people.”

Forty years after its release, the influence of the cult-favorite film Flashdance continues. The movie captured the spirit of its era before it was even clear what that era-defining spirit was. After its release, one could see elements from the film that went from the silver screen to the street, such as off-the-shoulder sweatshirts, the felicitous result of Beals coming to set wearing a sweatshirt that she had customized; leg warmers came out of ballet classes and were worn on the street; and Irene Cara’s “Flashdance…What a Feeling” blared on the radio.

One reason that few saw the Flashdance phenomenon coming was that the plot seemed to require too much suspension of belief from its audience. It tells the story of a welder who dreams of becoming a ballet dancer and performs sophisticated choreography at a nightclub where nobody strips. It sounds like crazy ideas pulled out of a hat during a desperate brainstorming session, but it’s a true story. Well, almost.

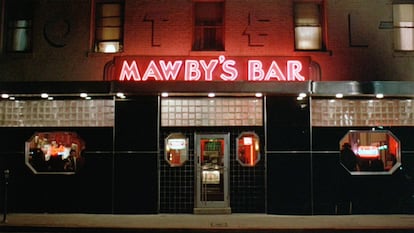

The seed of the story was planted in Gimlets, a Toronto bar that journalist Tom Hedley used to frequent. While seeking ideas to develop a script, he met the group of dancers who went on stage every night; most were single mothers or students who needed the income to survive. But Maureen Marder, who unloaded sacks of concrete at a construction site during the day, and Gina Healey, whose choreography was more artistic than erotic, were also there. In those days, burlesque shows were languishing, overtaken by much less subtle strip clubs. Marder and Healey were paid $2,300 for their consulting work, and Hedley used elements of their lives to write a story about three dancers, which he called Depot Bar and Grill. The project reached Paramount, where it remained stalled until producer Don Simpson decided to bring it to life in his first collaboration with Jerry Bruckheimer, a partnership that would change the face of Hollywood.

Like the people who chose her photo as the one they wanted to sleep with (or befriend), Lyne fell in love with Jennifer Beals. “I thought she was good. She had a vulnerability that made it work and made it less absurd,” he declared. Casting Beals as the lead also added an element that wasn’t in the script; it placed an interracial relationship at the center of the narrative. That wasn’t an insignificant detail; only 15 years before the film was made, mixed marriages were still banned in the United States. (Beals’ skin color went unnoticed by many, but the Ku Klux Klan sent her threatening letters for years.) For the first time in mainstream cinema, the black girl was not relegated to the role of a sympathetic friend to be the main character’s sidekick; the trope of the sassy black friend wasn’t applicable: here, the black girl was the main character and her friend, the angelic blonde, white girl, played a supporting role.

Robert de Niro and Richard Gere were approached to play Nick, Alex’s boss and lover. A then-unknown Kevin Costner, who had just shot an Apple commercial with Lyne, almost got the role, but in the end Michael Nouri was given the part.

In a film about dancing, the soundtrack was essential. For the titular song, they played it safe. The indisputable Giorgio Moroder and Irene Cara, who had played the lead role in and sang the hit song from Fame, were behind the iconic “Flashdance…What a Feeling,” one of the official soundtracks of the 1980s. But the song that was played most in aerobics classes was Michael Sembello’s “Maniac,” a song that had previously been shelved about a serial killer. The lyrics had to be changed from “he’s a maniac, maniac that’s for sure. He will kill your cat and nail him to the door” to “she’s a maniac, maniac on the floor. And she’s dancing like she’s never danced before.”

Even the formidable musical selection did not excite the people behind the production. “In the two weeks before Flashdance came out, I literally couldn’t get anybody on the phone. It was like everybody had run for the hills because they thought it was gonna be a total disaster. I didn’t know either. Paramount sold at least a quarter of their interest in the film in those two weeks. In other words, they saw the film, and thought, Well, this is gonna go down the toilet.”

Flashdance’s premiere seemed to vindicate those who predicted it would be a flop. At first, the movie’s box office debut was tepid, but word of mouth eventually made it one of the films of the year. “Suddenly, everywhere I went, everyone was wearing one-shoulder sweatshirts,” said producer Lynda Obst. The movie grossed $200 million and received four Oscar nominations. It won an Academy Award for best original song, beating out Barbra Streisand’s “Papa, Can You Hear Me?” from Yentl. But critics were not impressed by the numbers. Roger Ebert included Flashdance in his list of most hated films. Diego Galán was no kinder in the pages of EL PAÍS; in a review titled “The Spark of Nothingness,” he wrote: “this tale sporadically depicts poorly shot musical numbers with little appeal.”

But the public found the movie tremendously appealing; it still does. Some of the film’s scenes are part of the collective imagination and have been imitated or parodied for years, from The Simpsons to Deadpool, from Snoopy in Flashbeagle to Jennifer Lopez’s “I’m Glad” (J. Lo copies the final moment of the film shot for shot in her music video). Viewers were dazzled by the small details, such as the moment when Beals removes her bra under her sweatshirt, an everyday gesture that wasn’t in the script but Lyne decided to incorporate. As Lyne explained to The Hollywood Reporter, “She was just trying on one piece of clothing after another, and I guess for convenience, rather than rushing out to the dressing room, she took her bra off underneath the T-shirt or whatever, and I was just fascinated by the contortion. To this day, I don’t quite know how she did it. I watched her at the time, and said, ‘Shit, I gotta use that. That’s wonderful.’”

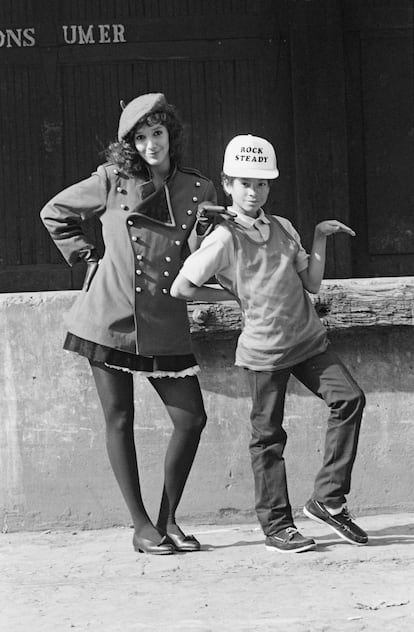

Throughout his career, Lyne has demonstrated attention to detail and distinct aesthetics. The Brit’s cinema makes everything beautiful, desirable, aspirational and modern. Forty years later, Beals’ entire wardrobe could appear in a current fashion catalog: the worn jeans, the baggy sweaters, the military jackets; everything is desirable, from her loft - one realizes one’s age when one considers how much it costs to heat those high ceilings in a city as cold as Pittsburgh - to Grunt, the precious pit bull with whom she shares it.

Lyne’s stylized images fascinated viewers and served to distract them from some of the film’s obvious incongruities. Alex was too young to be a welder and too old to take up ballet. Those details almost help disguise Paramount’s best-kept secret: while she’s gorgeous and a good actress, Beals was not a professional dancer. Indeed, she almost never dances in the film. French actress Marine Jahan did all the choreography, but she was not credited for it “so as not to ruin the magic.” But Beals herself had no problem admitting it: “Marine did all the dancing in the sequences they finally used on screen.... They used my face for close-ups, but when you looked closely you could easily tell the difference between the two.”

Marine agreed to stay out of the spotlight, despite knowing her role in the film’s success and the risks she took. During the dance in which a bucket of water falls on Alex, Paramount feared she would break her neck. ”It was a hell of a lot of water. Marine Jahan was very good, the way she just soldiered on and made it look like it was nice. But it was obviously a nightmare,” Lyne explained. “The movie gave credit to the dog and not Marine,” Flashdance choreographer Jeffrey Hornaday, who attended a screening with Jahan, said. “I’m sorry, kid. But you were great. They were applauding for you,” he told her at the end. “Yes, but they don’t know it,” the dancer replied, devastated to find out that her name did not appear in the end credits.

That wasn’t the only poorly kept secret, and there were other doubles for Alex as well. The final number featured four people; in addition to Beals and Jahan, professional gymnast Sharon Shapiro performed the acrobatics and, to the delight of those who watched the film on video, the breakdancing moment was the work of Richard Colón, a 16-year-old b-boy whose mustache can be seen if one pauses the movie at the right moment. Colón reluctantly agreed to wear tights but refused to shave. Colón was in the film because he had participated in a sequence, the relevance of which went unnoticed at the time. Lyne had fought with producer Michael Eisner to keep a minute of an urban dance that was beginning to make waves in New York in the film. Flashdance was the first film to show breakdancing; it even preceded Michael Jackson by showing the famous moonwalk for the first time. The Flashdance phenomenon coincided with the advent of MTV; the channel played Cara’s and Sambello’s music videos repeatedly. It was a turning point in the history of cinema that not everyone appreciates; from then on, all films aimed at young audiences considered that their images would lead to music videos.

The film’s success boosted the careers of those behind the cameras. Adrian Lyne became an important director with films like 9½ Weeks and Fatal Attraction; Basic Instinct made Joe Eszterhas the highest paid screenwriter of the 1990s; and producers Bruckheimer and Simpson dominated the box office during that decade thanks to testosterone-driven productions like Top Gun, Beverly Hills Cop and The Rock.

The film’s leading actors had a lower profile. Jennifer Beals returned to Yale and focused on her studies and independent films. She regained her popularity through her leading role in The L Word, a production about a group of lesbians that awakened her conscience and made her a passionate LGBT rights activist. Beals has now joined the Star Wars universe with The Book of Boba Fett. Michael Nouri never became the star his attractiveness suggested he would become. Sunny Johnson, Alex’s partner who gives up her dream of becoming a figure skater, died months after the premiere from a brain aneurysm. She was only 30 years old.

After Flashdance’s success, it was impossible for Paramount not to attempt a sequel. The film company tried several times, but Beals was a key player and refused. “I’ve never been drawn to something by virtue of how rich or famous it will make me. I turned down so much money, and my agents were just losing their minds.” But another movie wasn’t necessary. Much of the visual culture that followed, from MTV to the Netflix aesthetic, represents a sequel or, more precisely, a legacy.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.