The lost New York City publication that reappeared in a closet

Between 1968 and 1971, Steven Lawrence and Peter Hujar published 14 issues of ‘Newspaper’ — an underground tabloid that contained no text, only photographs

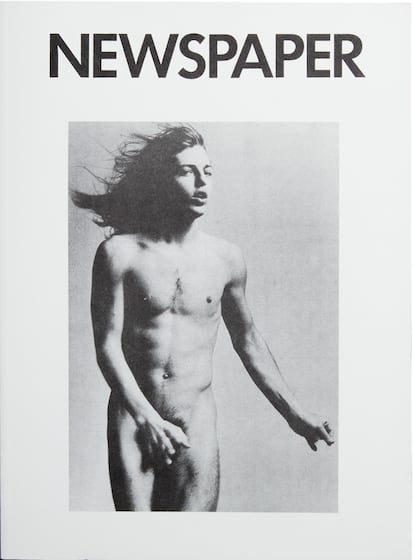

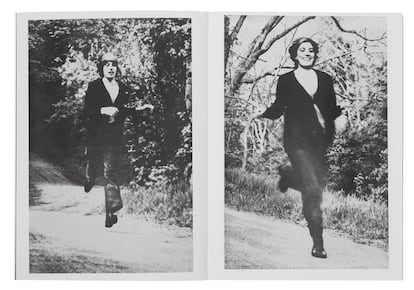

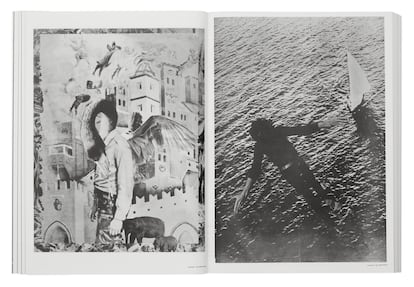

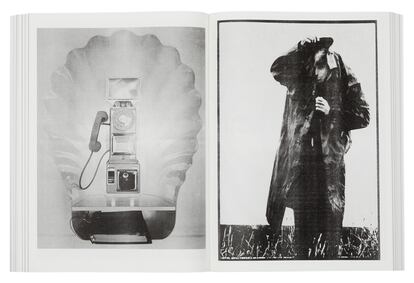

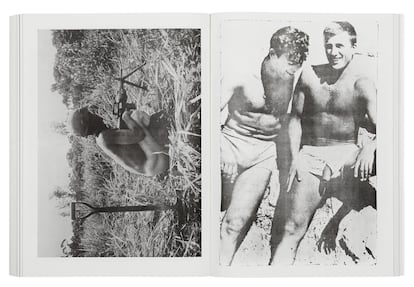

In mid-1968, a suggestive and daring publication began to circulate among the New York Bohemia. It focused solely on photography, containing no text. It circulated mainly through word-of-mouth and in places such as the emblematic nightclub, Max’s Kansas City, which was frequented by the hedonists of lower Manhattan. When opened up, the tattered, folded tabloid reached dimensions of 58 by 86 centimeters, allowing readers to hang its pages on the wall, as if they were works of art.

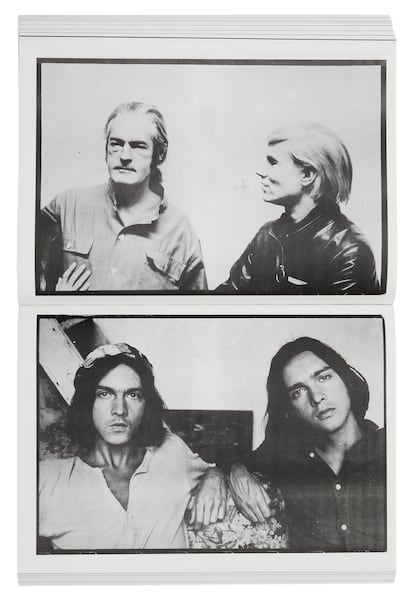

Among a long list of 48 artists, those involved in the publication of the magazine — of which only 14 issues were released — included Andy Warhol, Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Peter Beard, Peter Hujar, Christo and Jeanne Claude, Yayoi Kusama, Paul Thek, Roy Lichtenstein, Duane Michals and Lucas Samaras. The first two copies didn’t have a title, nor did the images bear the photographers’ names. The tabloid also initially dispensed with any list of credits.

The third issue hit the streets under the name of Ark. But, by April 1969, proper numbers were installed and the photographers and editors were credited, while the name of the publication was revised. Newspaper cost 50 cents.

Behind the risky publishing adventure was Steven Lawrence — an unknown 22-year-old designer from Texas — who benefited from the invaluable contributions of Peter Hujar and Andrew Ullrick when it came to choosing and editing content. Newspaper was, without a doubt, a more radical, experimental and relaxed publication than the already-established Village Voice. It gave space to an endless number of images with totally varied interests.

However, over time — perhaps due to the AIDS crisis that ravaged New York’s artistic community, or the precariousness of the publication’s format — Newspaper disappeared completely. Even in the Hujar archive, no copies were found.

But in 2015, a discovery was made. While working in the Danny Fields archive — named after the writer, musician and publicist who was part of Andy Warhol’s studio — art historian and archivist Marcelo Gabriel Yáñez discovered a bundle of copies in a closet. The yellow, crumbling pages aroused the interest of the researcher, who recognized works by Arbus and Avedon on the pages.

“Looking at an issue is a process similar to a ritual. The body is involved in it. [You need] a space large enough to house its full dimensions,” the archivist warns. Primary Information — a not-for-profit publishing house — has provided this space, taking charge of publishing the complete circulation of Newspaper. All 14 issues are now available within a single volume. Restored by Rick Myers and photographed by David Vu, it includes a timeline written by Yáñez.

Before putting out Newspaper, Lawrence had only recently settled in New York. Among his first contacts was Hujar — they were even lovers for a while. They also shared an apartment at 188 Second Avenue when the tabloid was being printed, between 1968 and 1971. The enigmatic photographer’s gaze is present in almost every issue: one can lose themselves in Hujar’s portraits of the beat poet Tuli Kupferberg, the blind composer Moondog, the members of the psychedelic theater group The Cockettes and the gay activist Jim Fouratt. There are also some nude shots, as well as photographs taken in the catacombs of Palermo.

Newspaper came at a crucial moment in Hujar’s career, becoming his main medium to exhibit his work. This was also the case for other marginal photographers, as the magazine represented an alternative space at a time when art galleries hardly exhibited photography.

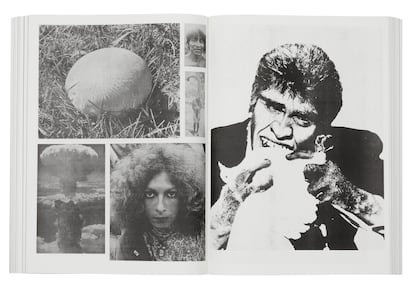

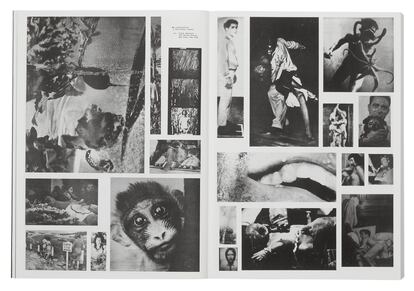

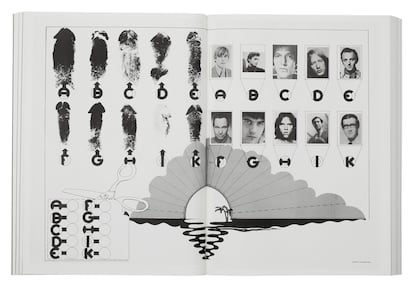

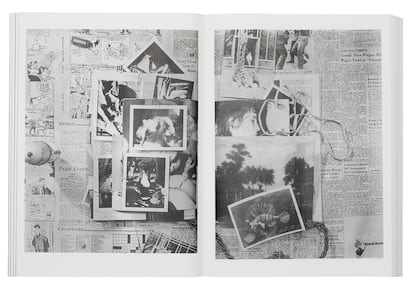

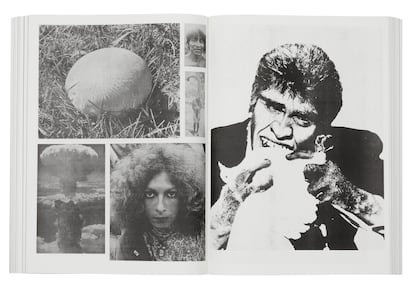

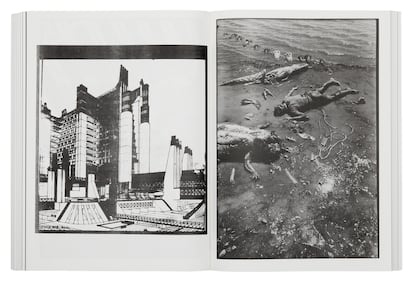

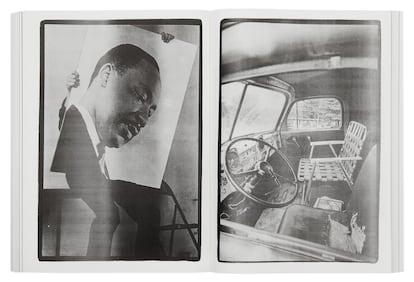

The unifying element of all the tabloid issues was the inclusion of a grid, made up of images collected from various sources. Entitled Environment, it could, for instance, accommodate chef Julia Child’s photograph of two monkeys alongside an image of a wax figure of Christ on his way to the cross. Similarly, an Indian yogi and a nude tattooed woman could be categorized together. It was precisely in this chaotic method of curating images that defined Newspaper’s innovative spirit.

“The chaos raised questions about the method by which images and news were read and understood by humans at that time, in the late-1960s, within a context that included the expansion of mass media, the Vietnam War and the social and spiritual revolutions of the counterculture,” explains Yáñez, in a text published by the Galerie Nationale du Jeu de Paume, in Paris. This thought-provoking chaos would also mark Hujar’s later work.

“Newspaper’s eccentricity and nerve were right for the moment,” notes Vince Aletti in The New Yorker. Around the same time as the magazine’s circulation, the writer and critic was a contributor to Rat, another underground publication. “When it came to visual impact, Newspaper was second to none,” he adds. While the tabloid could be politically radical at times, the sexual tendencies of most of its contributors didn’t go unnoticed, either. “Gender fluidity was commonplace in the East Village in the early 1970s. If the readers didn’t take it completely for granted, at least it didn’t alarm them,” the critic notes.

In 1970, the magazine was included in a renowned exhibition organized at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Titled Information, it was dedicated to contemporary conceptual art, under the curatorship of Kynaston McShine. Thus, what had started as an underground initiative became a work of art.

From the very beginning, the publication played with a dynamic that is located “between the visual reading of a tabloid newspaper and that of an artists’ magazine,” Yáñez explains. “[Newspaper] plays with the idea that artists deface the currency of the time: they consume the news, they change and transform the official story, they take the disposable and ephemeral nature of the day-to-day newspaper and elevate it to the category of art. The game of signifying art as garbage — and garbage as art — is something that Lawrence and Hujar played with in the publication [and] until the end of their careers.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.