Weird tales of our strange and monstrous world

A new anthology straddles the domains of Lovecraftian horror stories and science fiction

Oil rigs have come to life and take giant strides through the ocean on steel-pillar legs, searching for new oil deposits to quench a bottomless thirst. Puny humans that cross their paths are destroyed without remorse. Governments and armies cannot explain what is happening and are powerless against it. What’s more, the oil rigs are now procreating little oil-rig babies scurrying around the coasts!

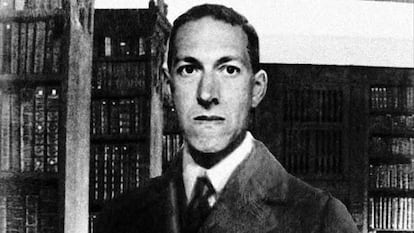

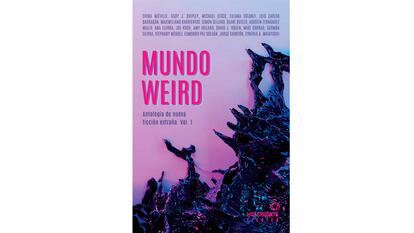

This story is called Covehithe, written by British author China Miéville, a renowned raconteur of strange tales. It’s the first short story in Mundo weird. Antología de nueva ficción extraña Vol. 1 (Holobionte Ediciones), an anthology of this relatively new fiction genre that includes translations of English-language stories and others written in Spanish. The use of the word weird to define this type of fiction comes from the American Weird Tales magazine that featured many H.P. Lovecraft stories in the late 1920s, including his well-known novella, The Dunwich Horror. The figure of Lovecraft looms large in this genre, which pushes the traditional Gothic tales of predecessors like Arthur Machen and Algernon Blackwood into new places where horror lurks.

In the New Weird genre, horror isn’t limited to ghosts, haunted houses, curses, werewolves and vampires. Now it comes from incomprehensible forces of nature and unimaginable cosmic gods (often with fearsome tentacles) harboring enormous and unbearable truths that dwarf insignificant and mortal humans. “Many literary genres like science fiction, folklore and classic Victorian horror converge in Lovecraft’s work. From there, we begin to see new stories with material and abstract components, a mixture of horror and science fiction,” said Holobionte director Federico Fernández Giordano, who edited the anthology with Ramiro Sanchiz.

Bizarre happenings

Ramiro Sanchiz explains the New Weird genre as stories “that don’t necessarily provoke visceral terror or horror, but rather an unsettled feeling that disturbs our relationship with reason and sanity.” The late English writer Mark Fisher had a similar view of the genre and described it as stories about impossible, bizarre things happening before our eyes, causing a cognitive dissonance that makes us doubt everything we believed about our world.

By the late 1990s, New Weird stories were increasingly set in more urban and contemporary environments and often incorporated new technological developments. The genre also established deep roots in Latin America. “When some well-known authors like VanderMeer and Miéville were translated into Spanish, many Latin American science fiction writers, especially in Buenos Aires and Bogotá, began to incorporate New Weird influences in their work,” said Sanchiz, noting that Vestigio, a publishing house started in 2018 in Bogotá, made Latin American weird science fiction a primary focus.

In addition to the opening tale about bellicose oil rigs that procreate, Mundo Weird offers a panoply of the bizarre: a mold that spreads over everything, causing madness; techno drug-addicted parallel dimensions; other-worldly voices that drive people to suicide; alien beings that invade human bodies to perpetuate their race; and endless, labyrinthine museums of curiosities in which visitors get forever lost. The anthology is divided into four sections. The first is dedicated to famous genre authors like China Miéville, Michael Cisco and Joe Koch. The following section presents the fertile Ibero-American weird world of Luis Carlos Barragán, Maximiliano Barrientos, Cynthia Matayoshi and Ana Llurba. The third section has four weird stories that have influenced mainstream literature by Edmundo Paz Soldán, Jorge Carrión, Agustín Fernández Mallo and Liliana Colanzi. The final section is dedicated to experimentation, with stories by Germán Sierra, David J. Roden and Amy Ireland.

Influence on contemporary philosophical thought

“There has been a strong resurgence of interest in weird and Lovecraftian literature recently, as can be seen in various aspects of contemporary culture,” said Fernández. Examples abound in literature, film and television: Lovecraft Country (HBO); Color Out of Space, the 2019 2019 film directed by Richard Stanley and starring Nicolas Cage; and Guillermo del Toro’s Netflix series, Cabinet of Curiosities. Curiously, New Weird and Lovecraftian influences have also penetrated recent schools of philosophical thought, such as the seminal Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (CCRU), an experimental cultural theorist collective formed in late 1995 at Warwick University, England. CCRU became a breeding ground for evolutions of the theories of Sadie Plant, Nick Land and Mark Fisher, and the new currents of speculative realism described in Graham Harman’s Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy and Eugene Thacker’s In the Dust of this Planet.

“In Lovecraft, philosopher Nick Land found a way to think of objects that exist independently of human sense – the Kantian noumenon – as something threatening, with jaws and fangs, capable of destroying everything we think makes us human,” said Fernández. Lovecraft’s ability to represent what cannot be represented also inspired Graham Harman’s “Object-Oriented Ontology,” which was subsumed in the current of speculative realism (or post-continental realism, as the philosopher Ernesto Castro calls it). “It’s also a tool that rejects the privileging of human existence over the existence of nonhuman objects and explores a post-humanist, post-anthropocentric thought, urgently needed in these strange times,” said Sanchiz. That is, to think of a world without us.

Sanchiz believes the surge in appreciation of the weird genre has much to do with current human afflictions like pandemics and climate change. As philosopher Timothy Morton observed, nature is no longer viewed as being at the service of humans. Instead, it is an uncontrollable, violent, incomprehensible, definitely weird and Lovecraftian force – a kind of “return of the great ancients,” as Lovecraft would say. Morton views climate change as a “hyper object” that surpasses human temporality and spatiality, a notion with resounding and terrifying echoes of the weird.

The same applies to the coronavirus, an entity from the microscopic world that gave us abundant proof of our insecurity and lack of control in this world. It turned the macroscopic world upside down, an increasingly post-human and post-anthropocentric world in which humans have an increasingly diminished role. “Faced with things like this,” said Sanchiz, “why keep thinking about the traditional mummies or zombies of humanism? The weird toolbox is replete with ways of discovering fresh ideas.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.