Goblin mode: The Oxford English Dictionary’s word of the year

Lying somewhere between laziness and nihilism, the concept celebrates our right to be slovenly in an increasingly goal-oriented world

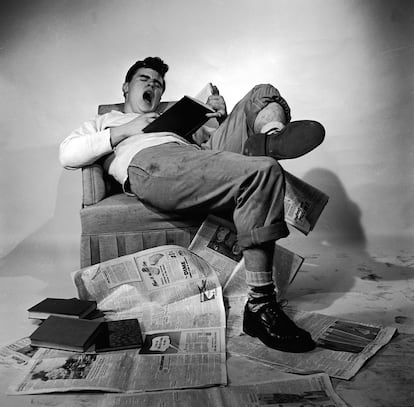

The term “goblin mode” won hands down as the Oxford English Dictionary’s 2022 word of the year, beating “metaverse” and the hashtag “IstandWith.” For those still unfamiliar with the term, it describes a type of behavior that is “unapologetically self-indulgent, lazy, slovenly, or greedy, typically in a way that rejects social norms or expectations,” according to the dictionary.

Ninety-three percent of the 340,000 people who took part in the vote opted overwhelmingly for “goblin mode,” first spotted on Twitter in 2009 but reaching its peak of popularity in Google trends in February of this year, after a Twitter user claimed under a fake headline that the rapper formerly known as Kanye West and Julia Fox broke up after she “went goblin mode.”

The president of Oxford Languages, Casper Grathwohl, admitted in a press release that this year they had been extremely surprised by the level of voting participation and enthusiasm for the goblin term. “Goblin mode resonates with all of us who are feeling a little overwhelmed at this point,” Grathwohl says in the statement. “It’s a relief to acknowledge that we’re not always the idealized, curated selves that we’re encouraged to present on our Instagram and TikTok feeds.”

But what is a goblin?

A goblin, simply put, is a creature from Central European folklore, similar to a mischievous leprechaun or an Irish leprechaun, like the orcs from Lord of the Rings or the goblinoids from Dungeons and Dragons. Not totally evil, they have a malicious side which is mostly selfish, and have little interest in doing good. The goblins of 2022, however, are not to be found in forests or mountains but on couches in urban homes, eating potato chips in a pair of pajamas with the remote or cellphone to hand in order to choose platform products that require no intellectual engagement. It is no coincidence that “goblin mode” was in the news in February and has been in the news again in December. Cold, flu and low energy levels tend to put us all into goblin mode.

On TikTok, the hashtag #goblinmode has been used as a counterpoint to #thatgirl, which refers to a girl who organizes her day in segments, gets up early to exercise, drinks vitamin shakes, gets her work done and still has time to enjoy a social life before going to bed early, having carried out a beauty routine of no less than 15 steps. Aesthetically, goblinesque – which is associated with sloppiness and dirt, greasy pizza boxes and unseparated garbage – is also the opposite of the cottagecore trend that promoted pastel colors and rustic pastimes, and which triumphed in 2020 and 2021.

Journalist Cat Marnell, an agent of chaos who recounted the many ways she had self-sabotaged herself in her 20s and 30s in her book How to Murder Your Life, has emerged as an expert on goblinism with a series of tweets in which she claims to embrace the lifestyle. “The power of goblin mode is that it takes over your body,” she says. “It is a scrambling of the brain. It’s when you act crazy, and you enter a very mythological space – you want to make trouble.” Less allegorically, she pointed out that in the digital realm everyone is trying to be perfect, and it’s good and refreshing to “get in touch with the strange little creature that lives inside you.”

It makes sense that the goblin mode reigned in the same year as another expression that could have been a finalist in the Oxford Dictionary, namely quiet quitting. Once the great resignation lost ground, analysis of sociological trends showed that many workers had opted to leave without leaving – in other words, to stay in their jobs, making no effort at all. That is when one comes up against another aspect of the goblinesque. Who can afford to be an idle and concupiscent creature at work, or even in life? Only someone who has accumulated a series of privileges or has them as a matter of course. The goblin mode doesn’t suit carers. Ask someone who takes care of children, elders or dependents when they last spent a whole day on the couch.

“As far as I’m concerned, the goblin mode is a ruse with which we try to deceive ourselves in the face of the obvious – that we are saturated by the liberal mentality,” says sociologist and analyst Iago Moreno. “Rather than pretending that we don’t care, I think we would do well to share more of our pain and powerlessness and politicize what we want to change.” Encouraging the goblin mode is, in the end, the equivalent to encouraging an alienated person to simply change their attitude instead of tackling the root of the problem, Moreno believes. “I think we need more rights, agreements, certainties, more than a change of attitude,” he says. “A change of attitude follows from that and not the other way around. Until then, we can’t be the goblin we’d like to become. We come with Santa’s elf chip pre-installed.”

The philosopher Eudald Espluga, who reflected on the phenomenon of self-exploitation (the anti-goblin) in his book Don’t Be Yourself, is also skeptical. “Beyond being chosen ‘term of the year,’ I don’t believe that the idea’s notoriety is accompanied by a cultural, social and material change through which personal self-realization can happen divorced from effort, commitment, work and constant improvement.”

The recent episode of Masterchef Spain in which one of the contestants, Patricia Conde, went into goblin mode and said she was tired and didn’t feel like competing, could be seen as a triumph for the goblin in her. Most of the public sided with Conde and thought the judges’ criticism of her was unreasonable.

However, according to Espluga, the goblin phenomenon has more to do with the need to detox on self-improvement, which Jenny Odell talks about in her book How to Do Nothing (Alpha Decay), than with a real paradigm shift. “What works in Patricia Conde’s case, I think, is not so much the vindication of refusing to do something, but the authenticity of recognizing one’s own discomfort,” he says. “It’s a bit like it being okay not to be okay.” In that sense, he believes the goblin mode works better as a cosmetic code than a political practice.

“The goblin is the necessary social choreography of BeReal users,” adds Espluga. “It is a calculated laziness that turns tiredness, fatigue and the rebellion against social imperatives into a personal brand image.”

In 2022, we have admitted that it’s okay to say “I’m not making it;” we have celebrated skipping the carbohydrate-free diet and the application of retinol. But while we want to believe we are lazy and naughty elves, in reality, we are still the hyper-productive and obedient creatures that the system needs to keep functioning.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.