How sex scenes are shot in Japan, where physical distance is the norm

Intimacy coordinator Momo Nishiyama discusses the challenges of choreographing romantic sequences in a country where kissing and hugging rarely occur in daily life

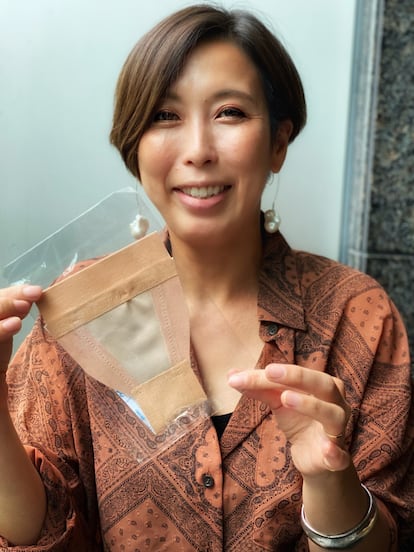

Momo Nishiyama’s job is to turn kisses, caresses and sexual acts into a simple choreography that actresses and actors can comfortably perform in front of the cameras. A graduate in Dance Pedagogy, she is an intimacy coordinator on movie shoots. Her profession is one of the newest in the film industry. She explains that some filmmakers and performers reject her services because they believe it will ruin spontaneity, while others fear her presence could become a moral critique of scenes that they see as crucial to cementing a romance or boosting box-office performance.

“I explain to directors that my role is not to judge; rather than deciding what they can or cannot do, my job is to support their creative vision,” says Nishiyama. Each project begins by gauging the emotional content of romantic scenes that involve physical contact. After consulting with a director about the type of sex he or she wants to depict, Nishiyama meets with the actors to make a list of their “boundaries.” She notes that the process does not enter into psychoanalytic territory: “I don’t do therapy.”

“If an actress doesn’t want a certain part of her body kissed, we look for other places to offer the director as an alternative,” Nishiyama says. That’s where flesh-colored patches, or modesty garments, come into play; they function to camouflage the breasts and genitals and ensure that an actor’s private parts are never seen on screen. After addressing issues of anatomy, the intimacy coordinator then focuses on choreographing the sex scene. Nishiyama breaks down each movement, much like the punches in a fight or the steps in a dance, which the actors memorize to repeat with their own bodies until each action becomes automatic.

Unlike cinematic fight scenes, which employ stunt doubles or train actors to avoid injury, simulated sex scenes have relied on unpredictable factors, such as the director’s intuition or the chemistry between actors. When filming intimate sequences, many novice actors fear that they will lose their jobs or be marked out as troublemakers if they refuse to comply with the (sometimes capricious) demands of a filmmaker or producer. The #MeToo movement has driven a number of initiatives in Japan to protect actors; they are similar to procedures that already exist in the film industries of the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom.

“Sex in Asian films is more subtle”

The Covid-19 pandemic affected Nishiyama’s work as a field producer for film shoots in Africa and she decided to retrain as an intimacy coordinator to pursue a new career. A friend encouraged her to take an online course through the Intimacy Professionals Association (IPA) in Los Angeles; the organization was founded by Amanda Blumenthal, who is considered to be the pioneer of the profession in Hollywood. She then began to apply what she had learned in Japan but realized that the demands of the job differed according to each culture’s attitude toward sex. Although statistics reveal that young Japanese people have less interest in sex, Nishiyama explains that, on average, Japanese films include more intimate scenes than Western movies do: “Sex in Asian films is more subtle; there’s more caressing, hand touching and a certain distance. In the West, [sex] is presented like a sport.”

She highlights the Japanese culture’s fascination with representations of sex and attributes the birth of a hedonistic culture, of which erotic prints or shunga are the most famous example, to the fact that the country’s borders were kept closed between the 17th and 19th centuries.

In addition, Japanese daily life is characterized by physical distance. People do not greet each other with kisses or hugs, and handshakes are rare, which helped to reduce the spread of coronavirus at the outset of the pandemic. But that reservedness also means that young actors are less prepared for such close contact, which makes them grateful for the presence of intimacy coordinators on set.

Currently, there are only two female intimacy coordinators in the entire country: Nishiyama and a colleague, who is hired by Netflix. Nishiyama gives free courses for actors in which she teaches them about their right to consent and, above all, how to say no. “One by one, I point out their body parts to them, and they are surprised by how many places there are where they don’t want to be touched. I explain to them that they have the right to say no, and that, in most cases, directors are willing to accept that decision. In the end, the most important thing for everyone is that the sequence gets filmed.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.