Chess cheaters of the past, present and future

The uproar caused when Carlsen accused Niemann of dirty play without offering any proof highlights the perils of cutting-edge technology

Just like the illegal doping techniques used by athletes, powerful computers have enabled chess cheaters to stay one step ahead of the rulebook. The current world champion, Norwegian Magnus Carlsen, has scandalously implied that American teen prodigy, Hans Niemann, played dirty to beat him. Niemann admits he cheated when he was younger, but not anymore, and the Norwegian hasn’t provided any solid proof. Chess trickery has existed since the 18th century, and is sure to thrive when computer chips are connected to human brains.

Austro-Hungarian engineer and inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen (1734-1804) would probably laugh about the Carlsen ruckus, especially the salacious details gleefully tweeted by chess fan and Tesla tycoon, Elon Musk. Some say Niemann used a wireless device inserted in his anus to read signals from a computer chess engine relaying the best moves. While technically feasible, this colonic cheating solution seems ludicrous because a simple micro-device hidden in Niemann’s ear would easily pass through the metal detectors used in all the major chess tournaments.

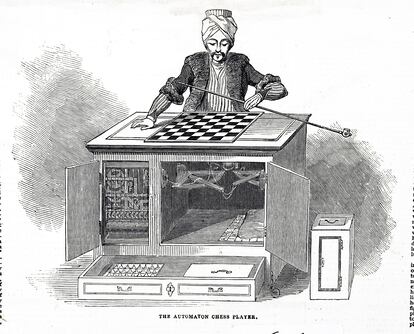

Why would von Kempelen, to whom Edgar Allan Poe once dedicated an essay, enjoy a juicy chess-cheating scandal? Because he had invented an eye-catching chess-playing machine called “The Turk.” This machine featured a mannequin in Turkish garb that toured European courts, defeating the likes of Napoleon and Catherine the Great. After von Kempelen died, “The Turk” went on tour in America and defeated Benjamin Franklin and many other challengers.

How did von Kempelen’s nachine work? Hidden in a box under the mannequin was a very small but expert chess player. Von Kempelen managed to evade detection for years by using a precisely angled set of mirrors. When all four sides of the box were opened for inspection by suspicious observers, the mirrors made it seem like the box was empty. The tiny chess player used a candle inside the box to see the chessboard from underneath, so von Kempelen would light candles on the surface to conceal the smoke rising from below.

Ingenious illusions like “The Turk” were needed to make a chess-playing machine with the technology available in the 18th century. But by the early 20th century, technology had progressed enough to enable renowned Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres-Quevedo (1852-1936), to dispense with the tricks and invent a chess-playing automaton that could checkmate a rook and king with a lone king. Torres-Quevedo’s unrestored invention is now maintained at the

Polytechnic University of Madrid. Although few Spaniards know his name, Torres-Quevedo invented the remote control, the Zeppelin dirigible technology, and the tourist ferry at Niagara Falls on the US-Canada border.

Almost 75 years later, an event that transcended the world of chess took place in New York. Russian world champion Gary Kasparov was playing the second game of the second series of matches against IBM’s “Deep Blue” computer, defeated by Kasparov a year earlier in Philadelphia, when the machine did something amazing. Instead of continuing to attack, Deep Blue made a blocking move, stunning those of us who were following the match from the press room. It was a move that an elite human player could have devised, but that type of critical thinking was inconceivable in a machine.

Kasparov lost the game and suffered one of the biggest traumas of his career. He accused IBM of cheating by resorting to human intervention at that critical point in the game. The two players were tied with 2.5 points each going into the sixth and final game, but Kasparov was so shaken that he lost again in a game unbefitting his genius. The shocking news raced around the world, and IBM’s stock soared. Kasparov repeated his accusations in the post-tournament press conference and demanded a rematch that never happened.

By 2007, there was no longer any doubt that the best chess player in the world was made of silicon chips. That scared many people who feared the prospect of world domination by machines, but human and computers learned to coexist well in the chess world. Moreover, what IBM learned with Deep Blue later made significant contributions to the field of molecular computing, which is used to manufacture complex drugs, forecast the weather and more. Soon after, the specter of computer-aided chess cheaters began to loom over the sport.

A player who said his name was John von Neumann, like the famous Hungarian mathematician who died in 1957, upended the 1993 Philadelphia Open with a series of masterful victories marred by some perplexing rookie mistakes. The player turned out to be an imposter and provocateur — he didn’t even know the rules of the game — who was listening through a small earpiece to a friend with a computer in another room. The hoax was discovered when some technical communication glitches resulted in some dreadfully poor moves.

Chess tournament organizers started banning cell phones from the rooms and players were scanned for devices before matches. Online chess websites were forced to develop algorithms to catch cheaters: if a player’s moves correlated highly with the moves a machine would make, they were called out for cheating.

But no world-class player has been accused of cheating because they all know their lucrative carreers would end immediately if they were caught, although a lower-level French player named Sebastian Feller (ranked 435th in the world) admitted to being helped by hand signs from his captain at the 2010 Chess Olympiad in Khanty-Mansiysk, Russia.

Then came the Niemann-Carlsen match at one of the most important slow-chess competitions of the year, the Sinquefield Cup in St. Louis (USA). The young American, who had already beaten world-champion Carlsen a month earlier in a rapid-chess tournament in Miami, did it again at the Sinquefield Cup. But this time, Carlsen shocked everyone by withdrawing from the tournament without any explanation. It was the first time he had ever withdrawn from a tournament. Carlsen only re-tweeted a video of Portuguese professional soccer coach José Mourinho saying, “If I speak I am in big trouble.” But the tournament organizers made it very clear that there was an implicit accusation of cheating by immediately imposing a 15-minute delay in the live broadcast of games. Since players only have 15 minutes to make a move, any external help would be foiled by the time delay.

But the ensuing uproar on social and news media was deafening, and became even louder when Niemann admitted in an interview with Chess24 (an online chess platform whose majority shareholder is Carlsen) that he had cheated in online games for a few years before he turned 16. Niemann denied cheating in live games and said he stopped cheating in online games after leaning his lesson. When Carlsen and Niemann faced each other again in an online rapid-chess tournament organized by Chess.com (which bought Chess24 in August), Carlsen made the very unsportsmanlike move of resigning the game after a single move.

Most of the chess grandmasters, including former champion Gary Kasparov, are demanding that Carlsen explain himself instead of silently throwing stones. The Norwegian has so far remained mum but may say something after the Chess.com tournament ends on October 2. In the meantime, Carlsen’s legion of fans have remained steadfastly loyal even though his veiled accusations are borderline slander.

Aside from the ethical undertones of the chess-cheating allegations, this scandal augurs the new dilemmas that will arise with technological advances. Some experts say that computer chips will be embedded with or connected to our brains within 10 years. This would be a major change in our lives and could usher in significant breakthroughs in many areas like disease prevention. But it will put an end to chess as a sport unless the chip can be deactivated during games. In any case, reasonable solutions should be sought, not absurd ones like Niemann’s offer to “strip naked” during games to prove he is not a chess cheat.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.