Fear and loathing in racist America: The true story of Dr. Gonzo

Hunter S. Thompson’s companion in his unhinged chronicle of a drug-soaked road trip to Las Vegas was Oscar Zeta Acosta, a Mexican American activist

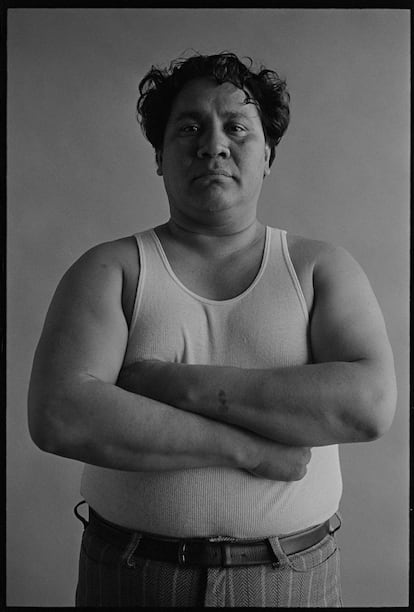

On February 20, 2005, gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson shot himself in the head in the kitchen of his Woody Creek home in the US state of Colorado. His son John was in the next room and mistook the gunshot for a dropped book. The life of Thompson and Raoul Duke, his alter ego in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, has been thoroughly chronicled by now. But what about Dr. Gonzo, the demented “300-pound Samoan lawyer,” who accompanied Thompson on the rollicking adventure to Las Vegas 50 years ago? His real name is Oscar Zeta Acosta.

Like Duke and Gonzo in the book, Thompson and Acosta had an explosive friendship, marked by a mutual penchant for bucking authority and an appetite for excess. When they met in 1967, both still had hopes for the future, although Acosta was much more aware of the world’s injustices. “Hunter, you son of a bitch, what I’m trying to do is build a society,” Acosta once wrote to Thompson. Acosta would always outdo Thompson in everything, even in the massive quantities of recreational drugs they both consumed.

Born in 1935 in El Paso (Texas, USA) and raised in California, Acosta was the son of an indigenous peach picker from the mountains of Durango in Mexico. As a child, he was taunted by his classmates for being “brown.” As a teenager, he was stopped by the police in his white girlfriend’s neighborhood for the same reason. Acosta idolized Ernest Hemingway and once started writing a book about his childhood — he was eight years old, and his father was off fighting in World War II when his uncle moved into the family home. The uncle drove his mother crazy, and she began to accuse her own son of being “an ugly and dirty Indian.”

Brown Power

Ever since he was young, Acosta searched for something to believe in. He tried the Baptist Church and the Air Force, both of which terrified him. He soon realized that the US social and judicial system was a machine that discriminated against the poor. He decided to study law in San Francisco, and became the first in his family to go to college. He dedicated himself to defending impoverished Mexican families, but began suffering from mental health issues and got addicted to the medications a psychiatrist prescribed for depression and anxiety.

He needed to figure out what to do with his life and went to Aspen (Colorado, USA) for a break. That’s where Acosta met Thompson in the summer of 1967, at the Daisy Duck bar. “I’m the trouble you’ve all been waiting for,” cried Thompson, who was struck by Acosta’s “terrible joy.”

After Aspen, Acosta moved to Los Angeles, where he became an activist and lawyer for Brown Power, the Mexican civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movement. He quickly attracted attention in the courtroom. Most of the lawyers and judges “were white, rich and old” wrote Acosta, while he was a tall, obese and furiously anti-establishment young mestizo, afraid of nothing. He wore garish ties to match his multicolored briefcase, and refused to charge clients who couldn’t afford his legal services.

Acosta won several cases and became a well-known figure around Los Angeles. The way to defeat capitalism was to organize! Get credit cards and don’t pay them off! He once defended a client by tearfully singing a Bob Dylan song in court.

Acosta was on a roll and decided to run for sheriff in Los Angeles County in 1970 on a promise to dismantle the violent police department. He won over 100,000 votes, but lost the election. Later that year, Thompson decided to run for sheriff in the small mountain town of Aspen. With Acosta as an advisor, Thompson campaigned on a promise to reclaim land from the clutches of property developers. That battle was also lost.

Molotov cocktails

In The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo (2017), a documentary about Acosta produced by Benicio del Toro (who played Dr. Gonzo in the film adaptation of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas), we learn that Acosta was obsessed with transforming the judicial system. Failing that, he would try to destroy it. But then Acosta started down the long road to self-destruction. He drank more and more, used all kinds of drugs and started going to work high. He learned how to make Molotov cocktails, and once blew up the yard of a judge he hated.

When Ruben Salazar, an influential Mexican American journalist, was mysteriously killed during a 1970 protest march, Acosta called Thompson to investigate. In 1971, Rolling Stone magazine published Thompson’s exposé, “Strange Rumblings in Aztlán”, in which he denounced the Los Angeles police force’s brutal racism and violence. Police animosity against Acosta and Thompson grew. To get out of Los Angeles for a while, Thompson invited Acosta along on a road trip to Las Vegas. Thompson had been commissioned by Sports Illustrated to do a well-paid, 500-word piece on a motorcycle race there.

“Hunter has stolen my soul”

Thompson never got around to delivering those 500 words, but instead wrote a deranged chronicle of the decline of the American dream — Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. The novel, which first appeared as a two-part series in Rolling Stone magazine in 1971 before being published in book form in 1972, launched Thompson to superstardom. But for Acosta, the aftermath of that crazy, crazy trip was very different. Shortly after the article’s publication in Rolling Stone, the magazine’s lawyers advised Thompson to send a copy to his erstwhile traveling companion. Acosta was shocked by what he read, and accused Thompson of portraying him as “a noble savage from the jungle.” Acosta wrote a letter to Thompson about it. “Did you ever wonder if I cared what you wrote about the Las Vegas trip?” asked Acosta.

Acosta also contacted Alan Rinzler, the head of Straight Arrow, Rolling Stone’s book division, and accused the journalist of recording his words without permission. “My God! Hunter has stolen my soul,” he told Rinzler.

But nothing was straightforward when it came to Oscar Zeta Acosta. To the publisher’s astonishment, Acosta was incensed — not about the accounts of drug use or criminal behavior — but because Thompson had transformed him into a “300-pound Samoan,” erasing his proudly held Mexican roots. He asked for redress and even tried to claim 50% of the rights to the book.

Half-slaves

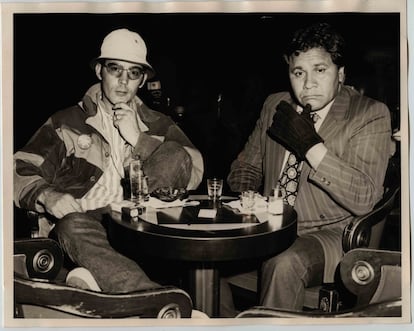

Acosta and the publisher ultimately agreed that a photo of him and Thompson would appear on the back cover of the book, with a caption indicating his real name. Rinzler also gave Acosta a book deal, and in 1972, Straight Arrow published Acosta’s The Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo, a semi-fictional account of his never-ending search for identity, and his mad struggle to fit into a mold designed by and for others. “They stole our land and made us half-slaves. They destroyed our gods and made us bow down to a dead man who’s been strung up for 2000 years … Now what we need is, first to give ourselves a new name. We need a new identity. A name and a language all our own,” wrote Acosta.

Phillip Rodriguez, who directed The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo, says that we need to reinterpret people like Acosta, who was so misunderstood and ignored at the time. “Acosta shows us that you have to fight for justice, and you don’t have to be perfect to do it,” said Rodriguez in a videocall. “You don’t have to be a saint to want to change things. You can have human desires and also have flaws. You can be drunk and also be effective. As he [Acosta] said, revolution doesn’t have to be boring. Remembering his work is important in times of rebellion like we are living now.”

Acosta’s incandescent life burned out way too soon. In 1974, Straight Arrow published his second novel, The Revolt of the Cockroach People, about the Chicano movement. A few months later, Acosta disappeared while traveling in Sinaloa, Mexico.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.