Paolo di Paolo, Italy’s most famous unknown photographer

As a documentary about him is released, the nonagenarian welcomes us into his home and clears up some of the myths

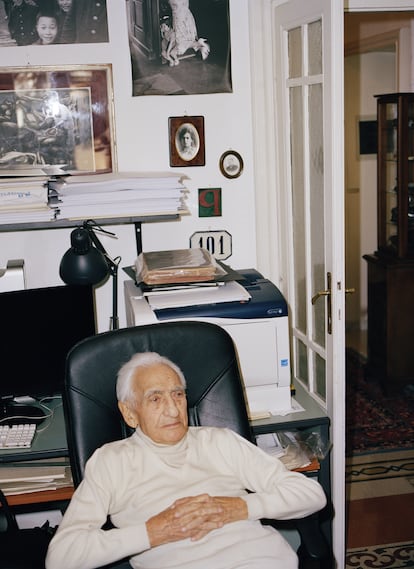

As his name occurs twice, so too does 97-year-old Italian photographer Paolo di Paolo believe he received two extra lives. When he was a few months old he was diagnosed with a fatal disease. The family doctor’s advice was to regularly bathe the baby in Negroamaro, a wine from southern Italy believed to have restorative qualities. No one knows how, but di Paolo was cured and today he is almost a century old.

The second new life came when he decided to disappear from photography after only 16 years, during which he became a legend in the field. As he settles into his chair, Paolo di Paolo jokes that he no longer bathes in Negroamaro. He does, however, drink around a liter of red wine every day.

His daughter, Silvia, accidently exhumed all his work one day while looking for some old skis in the attic. Now the holder of a repository that includes around 254,000 unpublished negatives from between 1964 and 1968, she accompanies him during the interview with EL PAÍS.

Di Paolo is revered by figures such as the designer Alessandro Michele and the photographer Bruce Weber, who recently premiered a documentary called The treasure of his youth: the photographs of Paolo Di Paolo. He lives with his wife in the central neighborhood of San Lorenzo in Rome. He decided one day in 1968 to abandon his photography career, locking this part of his identity inside the pile of old boxes that his daughter would find years later. It was not just any day but the day that Il Mondo, the weekly newspaper he worked for and that championed the work of photographers, closed. Sensing the advent of a more cynical world of paparazzi and celebrity, di Paolo decided never again to speak of the world he had photographed – the film stars, filmmakers, writers and journalists who adored him, and who occupied a world he felt was now lost.

“Who was going to publish my photos?,” he asks, saying the rise of television meant the end of long, elaborate photojournalism. “The final blow,” he says, occurred one day when he met with a newspaper editor, who said to him: “Bring me anything that has some spice.” “I left his office sad,” recalls di Paolo, saying he felt both physical and symbolic doors closing behind him. His work was not in “the world of scandal,” of salaciousness and intrusion. If he had decided to buy into this new demand for photographers, he too would have declined, he says, adding that, as such, “today we would surely not be here.”

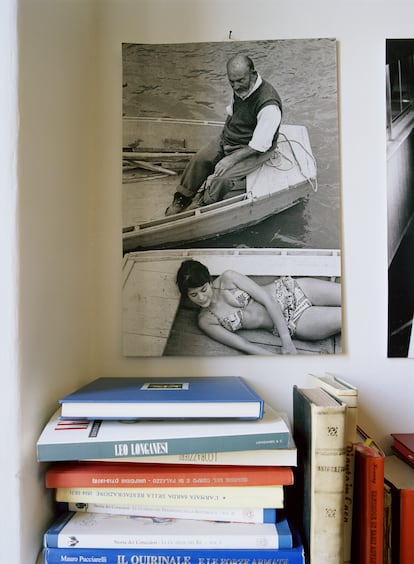

Di Paolo’s work is known for its oscillation between his delicate gaze and the forceful gravity of the people he portrayed which included Oriana Fallaci, René Clair, Giorgio De Chirico, Ezra Pound, Marcello Mastroianni and Anna Magnani. He also documented the almost hidden rituals of the old Roman nobility, such as the coming-out ball of Princess Pallavicini, where he was the only photographer allowed to enter, as well as political moments such as the funeral of Palmiro Togliatti, Secretary General of the Italian communist party.

Italy was already experiencing the first detonations of the economic boom that modernized the nation in the sixties and the accompanying social tensions that were staged from north to south. Di Paolo felt the fractures deeply and sought to represent them. He went to photograph the inauguration of the Autopista del Sol, the great ‘highway of the sun’ a bold piece of infrastructure that was supposed to unite the country and carry it forward; di Paolo climbed to the top of a hill and, from behind, captured a poor family living in a shack watching the first car speed through olive trees and fields, leaving them behind.

As a student, di Paolo wanted to be a philosophy teacher, until, on the eve of his college graduation, he stumbled upon a Leica III C in a shop window. It is perhaps this intellectual foregrounding that explains his concern with ethics at least as much as aesthetics in his work. The dawn of celebrity culture, he says, made him and his colleagues feel “ashamed to go down the street with the camera around our neck.”

“The paparazzi thing was a phenomenon fueled by Fellini,” says di Paolo, adding that the glamorous word of La Dolce Vita never existed. “He invented a whole world in his films, far from… a Rome that he did not know.”

Di Paolo began his photography career along with four or five friends who wanted to express themselves artistically in some way, he recalls. “We came from different experiences. We had enormous willpower, because we came from the end of the war. We were not unhappy because we did not know what happiness was. But suddenly we discovered the ability to dream and make dreams come true”, he explains.

They wanted the truth, an ethic that granted di Paolo extraordinary access to people like Pier Paolo Pasolini, who was a young writer and poet when di Paolo accompanied him one summer for a photoessay called The Long Road of Sand. The two spent half the trip in silence, driving along in the photographer’s MG convertible. The friendship led the filmmaker to open his doors for di Paolo to shoot film on future projects, such as The Gospel According to Saint Matthew.

Silvia, his daughter, recalls that “we never saw any stars” like this in family life. Not even she knew exactly what her father had been doing until she found the stash of prints and negatives in the attic.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.