Two photographers capturing the hidden side of the human face

Roger Ballen and Jacques Sonck, whose work will be on display at the Castilla y León International Photography Festival in Spain, look at the figure of the outsider from different perspectives

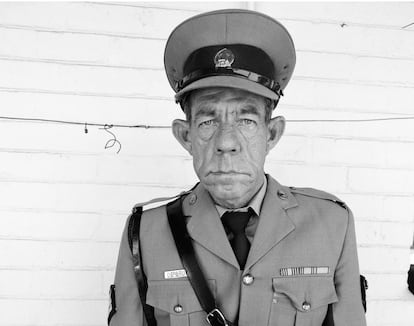

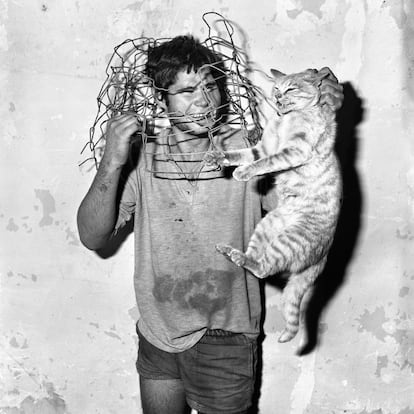

Sergeant F de Bruin, Department of Prisons Employee, Orange Free State is one of Roger Ballen’s best-known portraits. The photograph comes from the Platteland (1986-93) collection, which Ballen, who lives in South Africa, undertook to shine a light on a section of the white, rural population living on the margins and cut off from the dubious privileges offered by Apartheid. The huge and disproportionate features of his face and his melancholy gaze do not seem to belong to his body, and neither do they seem to correspond to a cog in the machinery of white supremacy. However, Ballen insists that the twisted wire behind the sergeant’s head (which is an obsession of the photographer), at the height of his eyes and ears, is what most caught his attention. Ballen says he is not interested in subjects that merely attract attention visually, but more in those that serve as a trigger, prompting the beholder to dig into the deepest and darkest parts of their own psyche.

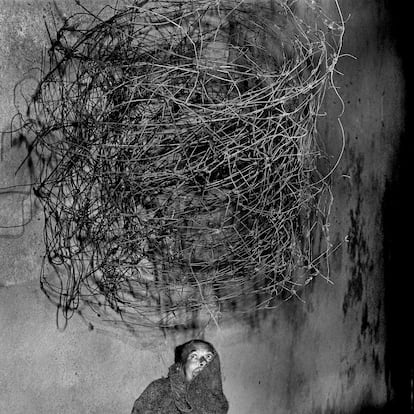

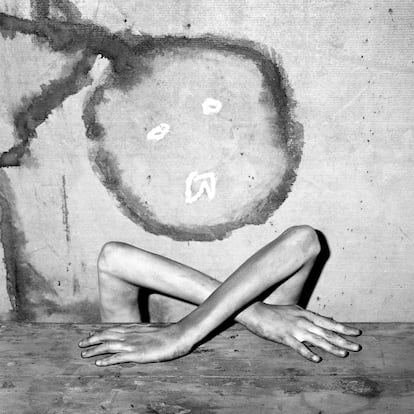

A geologist and psychologist by trade, after a career spanning five decades Ballen describes himself as a psychological and existential photographer. He achieved international fame though his disturbing work with subjects who are often outsiders within South African society. People who live in poverty, many of them with disabilities or mentally unstable, generally whites, and often framed in the ramshackle homes they inhabit, where they act in defiance of common sense. It is work that over time has become loaded with metaphors and theatricality, leaving the human form to one side to incorporate animals (which remind us we are just one more species on Earth), drawings and sculpture, which offer a much more complex and abstract narrative that on occasion blurs the border between fiction and reality.

“My photography is not about the people or the places in which they appear. They do not document a political or social reality. It is essentially a psychological experience,” Ballen, who is one of the protagonists of the second edition of the Castilla y León International Photography Festival tells EL PAÍS in a video call. Ballen will be displaying a collection titled The world according to Roger Ballen, made up of 50 photographs belonging to one of his most representative series, in which six themes predominate that have helped shape the author’s vision: wires, people, animals, reality vs unreality, drawings and color, inscribed in an esthetic that Ballen himself has come to describe as Ballenesque.

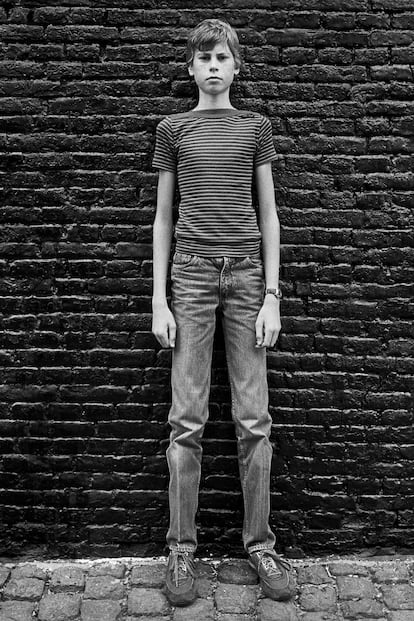

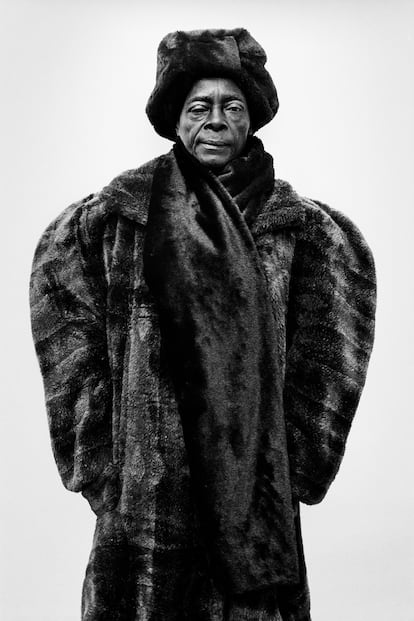

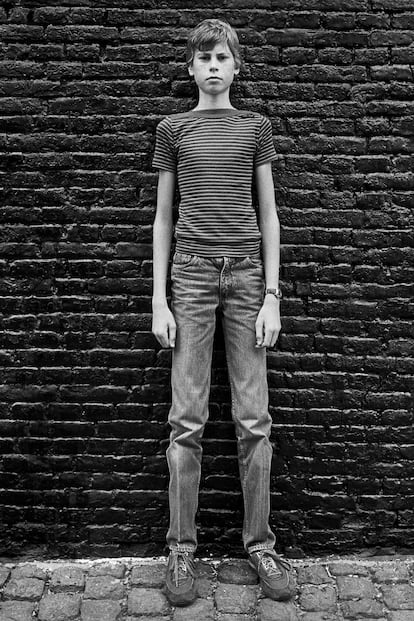

Jacques Sonck will also be at the festival with a series entitled Portraits, consisting of 40 photographs from a single ongoing series started in the 1970s. “I am interested in people who stand out visually,” he tells EL PAÍS. “Anybody who stands out from the norm in their appearance. Of any age, gender or race. Marginal or not. In principle I have a clear vision of what I am looking for, but I always let myself be surprised. In reality I am looking for peculiarity. And I emphasize it within a framework.”

If Ballen and Sonck share anything it is their early love of photography. Ballen, who was born in New York, grew up with the works of the great photojournalists of the era hanging on his walls. His mother worked for Magnum and often rubbed shoulders with Cartier-Bresson and Kertész. Interest in the medium also emerged at a young age for the Belgian; at the age of 12 he was awestruck by the beauty of cameras on display in the window of a shopping mall. If Ballen described his style as “documental fiction,” Sonck defines himself as “a documentary portrait photographer.” As such, he takes to the streets in search of subjects whose names he never asks (Antwerp, Brussels and Ghent tend to be his main focus). Some pose spontaneously, after a neutral background is found that decontextualizes the subject and emphasizes their peculiarity. Others are photographed at his studio, where he employs spotlights to sculpt their features. In both cases, they maintain a neutral and distant look. Without ridicule, but also without melancholy. “Without passing any judgment,” Sonck says, contradicting Richard Avedon’s view of portraiture: “The moment an emotion or fact is transformed into a photograph it is no longer a fact but an opinion.”

Sometimes Sonck focuses on a single detail, perhaps the tights or the arm of his subject. Sessions tend not to extend beyond 15 minutes. His photographs have no titles and are accompanied only by the date and the place they were taken. “They don’t need a lot of information,” he says. “I am more interested in the viewer using their imagination to complete the story. Everyone who poses for me is important. They are all different but they deserve the same treatment and respect.”

Both Ballen’s and Sonck’s works have been compared to that of Diane Arbus, something which Ballen does not seem to be in agreement with, as he points to the writer Samuel Beckett as the greatest influence on his career. “My work evokes the absurdity of the human condition,” he says. “In reality we are all outsiders in the psychological realm, and from there we all live on the margin in a certain way. We can’t predict what is going to happen, or control the majority of things in life. Thinking that one has control is an illusion.” Some of his critics have suggested a lack of empathy with his subjects in his emphasis on the extreme or the grotesque, something which also happened to Arbus, when Susan Sontag saw a position of privilege and superiority in portraying “pathetic people, who draw compassion as well as repulsion.”

Ballen responds by distancing himself from traditional definitions of beauty. “In my mind, those that we refer to as beautiful traditionally have their own anguish,” he says. “I can make anybody marginal in my photographs, even if they are not. I can transform them within a psychobellenesque esthetic. Let us take Picasso as an example. Whoever his portraits are of, they become Picassian. Good photography is like creating a painting.”

There is something very primitive in Ballen’s images, which take a viewer back to cave paintings. “My images are multidimensional and archetypal,” he says. “One of the reasons they stay with people is precisely because of this archetypal component that is found in the significance and the form. As such the spectator, subconsciously, is able to recognize the cave to some extent, or something more primitive, and to recognize it is part of their evolutionary development. These are difficult things to prove. The images can be as primitive as they are sophisticated. They are full of opposites; they are dark and disquieting at the same as they contain comedy and humor. Beauty and ugliness coexist in them. There is not a single word capable of expressing the coexistence of these dualities.”

In Ballen’s view, the most profound word in our vocabulary is nothing. “Nothing is death. And the greatest fear anybody experiences is death; generally, nobody wants to die,” he says. “The great mystery is where we came from and where we are going, and as such we are always dealing with nothingness. We are never free of it. We try but unconsciously the idea determines our behavior and that of all animals.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.