Shantytowns in Barcelona: in the shadows of history

Thousands of people lived in these slums throughout the 20th century

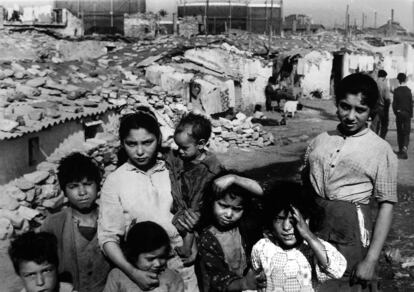

Visited by more than nine million tourists in 2016, Barcelona is considered a city that embraces innovation, tourism, style and design. This image, however, comes from a 20th century that was full of social transformation and waves of immigration. Thousands of people came from rural areas such as Andalusia to a city that couldn’t provide enough housing for them. Around 20,000 shacks had already been built by 1950 in different parts of Barcelona, leading to segregated shantytowns with no facilities but a strong atmosphere of solidarity. Can Valero in Montjuïc mountain, Camp de la Bota, and Somorrostro on the beach were just three of them.

Nowadays, people who lived there as youngsters still remember their daily lives in these slums. Despite being a significant part of Barcelona’s legacy, the shantytowns remained in the shadows for a long period of time. This, however, has started to change over the past few years. The Citizens’ Commission for the Recovery of Barcelona’s Shantytown Historical Memory has promoted the construction of commemorative plaques where these settlements used to be.

Somorrostro beach, the cradle of the Olympic Village

Somorrostro was one of the first shantytowns to emerge in Barcelona, on the beach next to the Barceloneta neighborhood. Exactly when the first shacks were built is not known, although newspapers mentioned the area around 1870. Few people lived there at that time, although Somorrostro became a big area for squatting in the 20th century, especially during the Spanish Civil War and post-war period. In 1905 there were 63 wooden homes in Somorrostro, but this number increased to more than 2,000 in the 1950s, when a population of 15,000 people piled into this slum.

Daily life and conditions in Somorrostro were difficult, especially in winter, because of its proximity to the sea. Waves battered the shacks whenever there was a storm, and firefighters and ambulances were sent out to help residents on several occasions. Besides the lack of electricity and running water, the muddy streets of Somorrostro were a breeding ground for epidemics, as raw sewage and industrial wastewater ended up there.

Around 20,000 shacks had already been built by 1950 in different parts of Barcelona

The settlement was known for the Gypsy community that lived there, with legendary flamenco dancer Carmen Amaya born there in 1913. From a Gypsy family, Amaya became successful around the world for her fast footwork, mastering some of the steps that had previously only been performed by a few male dancers. She also took part in a few Hollywood films and was even received in the White House.

The end of the Somorrostro shantytown came about because of the construction of Barcelona’s seafront promenade in 1957, although the final blow would be delivered in 1966, during the First Naval Week. Somorrostro beach was to host military maneuvers under the leadership of General Francisco Franco, who didn’t want outside observers to see the poverty of a shantytown. The forced resettlement set a precedent in Barcelona that was to be followed several times.

elpais.cat in English

From November 2016 onward, the Catalan edition of EL PAÍS, Elpais.cat, has been publishing a selection of news stories in English.

The texts are prepared by journalism students at the Pompeu Fabra University (UPF), who adapt content from Catalan current affairs every week, adding extra information and explanation to these stories so that they can be understood in a global context.

“Up to 1972, all the resettlements came about due to city interests, without taking human criteria into consideration,” says historian Oscar Casasayas. “Only the families that could afford it could actually relocate to an apartment. Other people were relocated to other shantytowns, so the sense of segregation was reinforced,” he adds.

The beach of Somorrostro is nowadays the Olympic Village, which was built for the Olympic Games in 1992. However, since 2011 a plaque dedicated to the shantytown honors the Somorrostro name.

Can Valero, a forgotten hill to die on

Located on the hillside of Montjuïc, Can Valero was the largest shantytown in the city during the Spanish dictatorship. Its particular location, close to Plaça Espanya but separated from the urbanized city, allowed Can Valero to grow rapidly. Montjuïc harbored several generations of workers who had come to a city that offered plenty of work but no affordable housing.

Rafael Usero and Francesc Banús lived in the mountain as children. Defining themselves as proud ex-slum dwellers, they now walk though Montjuïc recalling what the shantytowns used to be like.

“The truth is that I wasn’t unhappy in the mountain,” says Rafael Usero, who was born and raised in Montjuïc. The son of Andalusian immigrants, he lived in a shack that his family built themselves “My parents bought a little piece of land and built a hut that was split in two and shared by two families,” he explains. This was common in the 1950s when many newcomers bought small parcels of land from owners in the city who had used them as gardens or orchards.

Francesc Banús arrived at Can Valero at the age of nine and lived “in what used to be a tool hut in a small orchard.” The hut had belonged to his grandfather, who managed to buy the land after working as a tiller for a wealthy city doctor. “It was very simple, about 25 square meters, divided into three spaces,” he says. The four family members – his mother and three children – slept in bunk beds in the only bedroom in the shack.

Electricity was scarce and cooking was initially done by burning coal, “although some people even used petroleum”

He recalls that their home was next door to Can Valero, “a house with a snack bar that gave its name to the surrounding area”. Both Francesc and Rafael agree that this spot was crucial, serving as the commercial and social center of the neighborhood, the place where people would go just to talk to each other.

The settlements in the mountain lacked basic facilities. Electricity was scarce and cooking was initially done by burning coal, which was later replaced by gas stoves “although some people even used petroleum,” Francesc says. “Some of our duties as children were to fetch water from the few fountains we had, and to buy carbide to light the shacks,” adds Rafael.

School was vital in the children’s daily life. It was initially run by a Carmelite priest, Father José Miguel, and later by nuns of the religious order of Saint Teresa of Jesus. In fact, most of the area’s social life was organized around the church. “There was a whole bunch of activities around the parish: soccer, a choir and even a band,” Rafael recalls.

Another important institution was the scout group, which is where Rafael and Cesc met. “Together with the creation of a youth discussion group, it led people to start questioning certain subjects and to become more aware of societal roles,” Rafael explains. While the children learned, the adults of Can Valero came together in La Esperanza Family Association to press the City Council for social improvements and “decent apartments.”

From horizontal to vertical shantytowns

Between 1956 and 1960, the population of Barcelona increased by 260,000 people, of whom 78% were from other parts of Spain. The construction of the city’s underground system and the Barcelona Universal Exposition of 1929 attracted thousands of people looking for a job.

Camp de la Bota was a shantytown located on the north seashore of Barcelona, and was home to up to 103 shacks in the late 1960s, according to historian and teacher Josep Maria Monferrer, who personally experienced the transformation of Camp de la Bota.

“Workers from Andalusia were fleeing hunger and misery; people from rural areas in Catalonia also came, and some of them were leftists who hid from Franco’s repression in the shanties,” he says.

More than 700 families lived in Camp de la Bota. “The shacks were so small, that’s why people used to live their lives out in the streets. Everyone knew everything about everybody else and, although there was some confrontation between families, the social fabric was very strong,” says Monferrer.

In 1964, a member of the council described how the residents of Camp de la Bota lived: “The vast majority of the people are in a deplorable state. There’s a lack of drinking water, no proper removal of wastewater, and plenty of insects and rats that bring diseases.”

There’s a lack of drinking water, no proper removal of wastewater, and plenty of insects and rats that bring diseases

Until 1989, dozens of families were still living in the settlement. “Public housing couldn’t cope with the number of people living in the shantytown,” explains Monferrer. But with the Olympic Games in 1992, the coastal zone acquired a new real estate value, which meant that Barcelona “had to clean up the image of the city.”

Monferrer was the principal at the first school in La Mina, one of the neighborhoods where people from Camp de la Bota were relocated to.

“Josep Maria de Porcioles, the mayor of Barcelona for 16 years, started building housing to get rid of the shacks, but he forgot to build facilities such as schools,” says Monferrer. To make things worse, the subsidized housing turned out to be different from what most Camp de la Bota residents had expected. “We organized a social movement because we had idealized what it would be like living in apartments, but we just ended up living in a vertical shantytown,” says Rafael Usero.

Residents of these areas are now demanding recognition for Camp de la Bota. “Cement has eliminated everything, we can’t get to the sea. Our origins are in this shantytown and there’s only a memorial plaque,” says the president of the neighborhood association of El Maresme, Santos Pérez.

Prejudice and admiration

The phenomenon of shantytowns is often presented as “the other Barcelona,” a separate reality. Both Francesc Banús and Rafael Usero agree that there was a certain contempt for shantytown inhabitants. This made them feel self-conscious about their situation, “as if our isolation was our fault,” Francesc says. He adds that it was common for people to conceal the fact that they lived there: “It was easier to say we were from Plaça Espanya or Poblesec.”

And yet residents of these shantytowns had a certain feeling of respect for Barcelona. Smiling, Rafael explains how the few times he went into the city, his parents dressed him in his Sunday best. “Mom told us to behave properly because in Barcelona everyone was really well mannered,” he says.

Now, with the passing of time, they feel no shame about their shantytown origins. “Our situation was circumstantial, it wasn’t what we wanted,” says Francesc. While most of the city saw them as a suburb, they considered their shantytown as a working-class neighborhood which functioned as a town where “people knew and helped each other.”

Monferrer agrees with this idea of a sense of fellowship: “There was a lot of solidarity,” he says. “Seeing how they helped each other, one realizes how human beings can adapt to certain situations and keep their dignity.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.