Cannibalism and mouth-to-mouth feeding: Scientists uncover secret life of bees in new videos

Researchers at Goethe University have shared previously unseen glimpses of the life of the flying insects, after installing cameras next to a hive

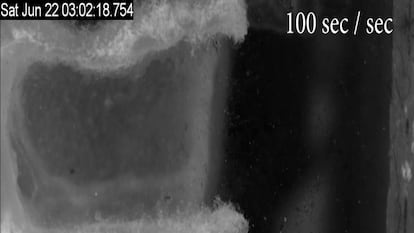

Paul Siefert of Goethe University’s Bee Research Institute thought he knew a fair amount about western honey bees – until he was able to film inside their hive. The results drawn from thousands of hours of video footage were published this month in the Plos One scientific journal, and included some serious surprises.

Siefert, the chief researcher in the study, observed the bees eating weaker specimens of their own kind. He explains: “In our observations, cannibalism generally happened without a visible cause, suggesting that workers perceive chemical information to identify diseased, deceased, parasitized or maldeveloped offspring.” The footage also showed that the insects cleaned themselves and each other, and the surface of a cell, all with the aim of keeping their hive clean and functioning. According to the researchers, cannibalism is also an effective way for the colony to prevent mold and fungi from growing on the offspring that die.

For Siefert personally, the most surprising thing he saw in the videos was the different reactions of two worker bees to an invader. “The two bees entered a cell in the hive in which there were varroa mites, a parasite that affects them. The first one did nothing, wasn’t bothered at all, but the second one – which entered just a couple of minutes later – attacked the mites with force,” says Siefert. One reason to explain this may be that hive hygiene and protection behavior is learned throughout life. Another reason, Siefert adds, could be genetic differences. “All worker bees are sisters, but they may have unequal genetics because they come from different parents,” he explains. “A single queen mates with several drones.”

Bees act as pollinators and without them, plants could not reproduce to feed humans and other animals. Studies show that bees pollinate 170,000 different species of plants, and at least one third of every spoonful of food humans eat depends on pollination. Despite their importance, millions of bees are killed each year due to the indiscriminate use of fertilizers and pesticides. Siefert hopes that his study “can also help ordinary people recognize the importance of these flying insects and the consequences of their mass death.”

The Goethe University study also reveals other unique processes that are described in print for the first time, such as the mouth-to-mouth feeding of larvae and how cells containing offspring are kept temperature-controlled to ensure their survival. The scientists say that though the videos do not offer definitive answers to many questions about bee life, they serve to accurately record and identify the behaviors of these insects.

Although the western honey bee lives in very large colonies of about 80,000 individuals, the hive’s success is determined by the behavior of every member. The videos make it possible to analyze and compare everyday activities such as nest building, foraging, temperature regulation and hive defense – all of which require teamwork.

To get around the problem of filming in an intricate structure, the researchers built a beehive with a glass pane turned 90 degrees to view inside the cells, and filmed with a special camera set-up. “To build the most appropriate and affordable light source, I bought metal serving bowls at [furniture and home accessory store] IKEA,” Siefert said. “It was an interesting task to convince our funding partners of the reasons why I needed a pair of bowls for my research.”

Siefert wants to use the videos showing these strange and complex bee behaviors to raise awareness in schools and non-scientific communities, and to learn ever more about these fascinating insects. “Future researchers will be able to test their hypothesis about bee behavior by observing videos. Furthermore, this could be expanded and compared with other insects living in social colonies,” he says.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.