The underground lair of La Luz del Mundo’s ‘apostle’

The Hermosa Provincia temple in Mexico is a symbol of the power of La Luz del Mundo church, but it is also a monument to the most terrible secrets and accusations against its leader, Naasón Joaquín, who is awaiting trial in the United States on charges of sexual abuse, possession of child pornography and human trafficking

The apostle’s

lair

Hundreds of thousands of the faithful stood before him, dressed in white and weeping inconsolably. “Open their eyes so they can see Your glory,” declared Naasón Joaquín, leader of La Luz del Mundo (The Light of the World) church, as he raised his arms in the center of the atrium.

Joaquín was holding forth in “the largest religious temple in Latin America,” a pyramid structure 83 meters high made from 5,000 tons of steel, and that took almost a decade to build.

Behind him, the advent of “the greatest feast on Earth” – the Holy Supper – was announced by the chanting of the choir. It is the religious organization’s most important celebration, to which the parishioners are summoned every August 14 inside the church’s flagship temple in Hermosa Provincia (Beautiful Province), in the Mexican city of Guadalajara, drawn by the promise of eternal salvation.

Beneath the temple, which embodies La Luz del Mundo’s power, lies a series of tunnels or passages as they have been described by former members of the congregation, though the church itself describes the space as a basement.

A secret place, this underground warren is the alleged scene of the terrible crimes that the leaders of the religious organization are accused of. “I have seen the tunnels and I can vouch for the fact they exist,” says Sochil Martín, a former assistant to Naasón Joaquín who reported him for multiple cases of sexual abuse. In that same underground network, another former collaborator, Alondra Ocampo, was raped as a child, according to her lawyer.

That Holy Supper in August 2018, was the last one led by Naasón Joaquín, known as the Apostle of Jesus Christ to his followers. Ten months later, he was arrested at the airport in Los Angeles after landing there in a private jet. Joaquín was dressed in a suit; in one hand he held his phone and, in the other, a briefcase. Inside his luggage, the authorities found an iPad containing a video of a naked 14-year-old boy, masked and receiving oral sex. The woman performing the fellatio, according to testimonies presented by the prosecution, was the teenager’s aunt. Other images of minors having sex were found on Joaquín’s electronic devices. Claiming to have more than five million followers in nearly 60 countries and proclaiming himself to be God’s representative on Earth, Joaquín was about to stand trial in California on charges of more than 30 crimes, including possession of child pornography, sexual abuse and human trafficking.

During the hearings, the prosecution claimed that Joaquín surrounded himself with a group of teenage girls who were selected to perform domestic chores for him. According to the prosecution, women who served as assistants were in charge of recruiting the minors, both at the Guadalajara headquarters and in Los Angeles. They would then put together a dossier with information about the candidates: their names, their photographs, their family tree and their families’ involvement in the congregation. The leader would instruct his close circle on how to approach them and explain what he was looking for in the girls. “The younger the better,” Joaquín said, according to the testimony of one former recruiter quoted in the trial. “They are purer and have more love for me.” Eliezer Gutiérrez Avelar, the minister in charge of public relations for La Luz del Mundo, maintains that the accusations are “false and unfounded,” as does the church itself.

Three weeks before Joaquín’s arrest, on May 15, 2019, La Luz del Mundo had been in the news on account of its political power. Thanks to contacts in the Mexican Senate, the apostle had received a unique tribute for his 50th birthday: the party was not held in the Hermosa Provincia temple but in the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, a landmark venue reserved for cultural events that does not usually celebrate any kind of religious act. According to Gutiérrez Avelar, what took place in the Bellas Artes “was a 100% cultural event” and “no religious activity was carried out.”

In the midst of public scrutiny, the cult leader flew to El Salvador to meet with President Nayib Bukele and together lay the first stone of La Luz del Mundo City, an architectural project covering more than 100 hectares of El Salvador’s capital. That month of May, Naasón Joaquín appeared to be at the height of his influence in Mexico and Central America. Less than a month later, he was sleeping behind bars in the United States.

The accusations

Serving and being close to the apostle was seen as “an honor” in the community; “a blessing.” But, according to the California Attorney General’s Office, the girls who were recruited to assist Naasón Joaquín later realized that their tasks were not limited to cleaning and making coffee. Alondra Ocampo, a recruiter who found the group from Los Angeles, would later tell them that, as the Bible says, kings had the right to concubines and that, since this was God’s servant, any sins they committed with Joaquín would be “forgiven.” According to the prosecution, Ocampo bought them outfits, took them to hotels and organized photo sessions in which the girls were forced to pose naked or in lingerie, perform lewd dances or kiss each other while showering.

The preliminary hearings, based on evidence presented by the prosecution, also alluded to scenes of explicit sex between Joaquín and the girls. The testimony of one of the complainants states that she was raped twice and forced to perform oral sex three times. According to Ocampo, should the girls refuse, they would be considered an “abomination.” Their families, moreover, would be devastated as they would have dishonored the apostle.

After being singled out as an accomplice and accused of 35 crimes, Ocampo made a deal with the prosecution in October 2020 in a bid to reduce her sentence, and pleaded guilty to four charges. Three are related to contacting minors for sexual purposes and the fourth to penetrating another person against their will.

The apostle is a living God, an unquestionable figureElio Masferrer, anthropologist

“What we know for sure is that Naasón asked her to find girls to be with him and pressured her to watch his back and do his dirty work,” says Fred Thiagarajah, Ocampo’s attorney. “Alondra did it because this man was God’s representative on Earth; she has been indoctrinated all her life to believe in that and in the Joaquín family.”

Ocampo’s family joined the church a year after she was born. Her lawyer says that when she was eight or nine years old, her parents took her to a large celebration at the Hermosa Provincia temple. The children were separated from their families and divided into groups by sex and age. One of La Luz del Mundo’s workers approached her and told her she had been chosen to meet Samuel Joaquín, Naasón’s father, who headed the organization for more than 50 years. Ocampo was taken through a “secret tunnel” and on meeting the apostle Samuel, she was told she was “special” and that he had selected her “as his wife. “He then raped her,” says Thiagarajah.

After the rape, Ocampo was told that what happened had been a “blessing,” but that she should keep it a secret because “other people wouldn’t understand” – instructions she would later impart to the girls under her care. According to Thiagarajah, the abuse continued for years throughout her childhood and adult life. Meanwhile, the church spokesman insists that these accusations are “unfounded” and “deeply offensive to the church’s members.” As far as Naasón Joaquín’s lawyers are concerned, Ocampo is only seeking to curry favor with the prosecution.

This is not the first time the leadership of La Luz del Mundo has had to wrestle with such accusations: the temple where Ocampo’s lawyer claims his client was raped by the apostle Samuel was built after the congregation became splintered in the 1940s, when a quarter of the flock left the church, alleging that the apostle Aarón – Samuel’s father and Naasón’s grandfather – had amassed wealth at the expense of the church’s poorest members, and had raped Guadalupe Avelar, a 13-year-old girl. For the organization, the accusations, past and present, are simply a sign that its leaders have been “attacked and persecuted for their beliefs for generations.”

A messianic construction

La Luz del Mundo was founded in December 1926, after Eusebio Joaquín had a “revelation” telling him to restore the original Church, far from the “deviations” of the Catholics after the death of Jesus.

Influenced by the arrival of Protestant preachers in the north of the country, Eusebio Joaquín, who had fought in the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), left military life for his religious calling and adopted the name of Aarón, the apostle of Jesus Christ. Partly due to its former participation in the Protestant-style Iglesia Cristiana Espiritual – Spiritual Christian Church – and also due to the Pentecostal tone of the religious services, La Luz del Mundo is often mistakenly described as an evangelical church.

Rather, its theology revolves around the idea of restoring the true Christian faith and also around its leadership, which has an apostle to guide the congregation. The figure of the apostle is indisputable and his command is decreed by divine right: in practice, explains the anthropologist Elio Masferrer, this has made it easier for the Joaquíns to establish themselves as a sacred dynasty among their followers. “The apostle is a living God,” says Masferrer.

“It was Pharaonic; they told us it wouldn’t hold up”Fernando Zamorano, in charge of structural design

While Catholics have the Vatican and Mormons have Salt Lake City, the holy city of La Luz del Mundo emerged in 1952 in a popular neighborhood in the east of Guadalajara, the third-most-populated city in Mexico, with the purchase of 14 hectares. The Hermosa Provincia (Beautiful Province) colony consolidated the formative stage of the organization, but the Promised Land lacked something. Under the leadership of Samuel Joaquín –the sixth of Eusebio Joaquín’s seven children – who took control of the church after the founder’s death in 1964, La Luz del Mundo entered an era of expansion and it was decided a new temple should be built that would act as its headquarters and reflect the congregation’s growth. “What this community needed was a symbol of unity and identity, something that would provide it with a face before the world,” says Leopoldo Fernández Font, the temple’s architect.

“It was Pharaonic,” says Fernando Zamorano, the engineer in charge of the structural design. Lasting more than nine years, the construction of the temple began in July 1983 on an elliptical plot of land measuring 60 by 90 meters. At the beginning, Samuel knew what he wanted, but not how it could be done: he wanted to have a center of worship that would house the largest number of faithful, he wanted a unique design, and he wanted it to be taller than the Guadalajara Cathedral. La Luz del Mundo church gave the architects the Greek Parthenon as a reference for timeless quality, and the Islamic mosques for beauty, according to Fernández Font.

The architect came up with a pyramidal building, an enormous multi-layered cake with inward-curved shapes meant to symbolize open arms embracing the four cardinal directions. These concave spaces were fitted with skylights forming a kaleidoscope of 112 rays of natural light: the Light of the World. The top, which is 83 meters above the ground, is capped with a sculpture representing the duality between father and son. Nobody had ever seen or built such a design before. Authorities questioned its stability, and building licenses were a long time coming.

“They told us it looked like a castle made with beer cans, and that it would not hold up,” laughs Zamorano. The structure finds inspiration in natural elements – halfway between a whirlwind and a sea snail – and its design required geometric calculations that tested the powers of the computers available at the time. It also required 5,000 tons of steel. To put it in perspective, the Estadio Azteca stadium in Mexico City, the largest in the country, required 1,200 tons of laminated steel and 8,000 tons of rods to hold it up.

But building Samuel’s pyramid required a lot of manpower. So he called his parishioners, who erected the temple without getting paid for their work. Their first task was to take down the old temple and rebuild it in Colonia Bethel, an area in the city of Guadalajara located just a few kilometers from Hermosa Provincia. “The faithful worked like little ants,” recalls Zamorano. There was a minority group of workers who were familiar with construction trades, but most were church members from other cities who received a couple of days of training and worked at the site for a few weeks. At the peak of construction, there were more than 500 people working simultaneously on tasks that could take up to two consecutive days to complete.

Because the building site was located in the middle of a residential area, the use of heavy machinery was very limited. The speaker system that once played religious hymns and psalms was now urging volunteers to pick up concrete slabs. Nearby homes became shelters that offered food and accommodation to the workers. “It was a messianic construction,” says a source who was once part of the church leadership. “We’re talking about children, women, elderly folks... Extremely humble people who were working as though inspired, giving it everything they had, with nothing held back.”

The result was a building able to accommodate more than 12,000 people, and which can be opened so that tens of thousands more may follow the religious services. The monumental Temple of Solomon in Brazil, owned by the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, can hold 10,000 people, making it similar in size to the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City. This is why La Luz del Mundo holds that theirs is the largest temple in Latin America.

The former church official says that construction cost more than $50 million, but those who were involved in the process admit that there were practically no labor costs at all, with the exception of food. “Notwithstanding the speculations that award disproportionate importance to the efforts and solidarity of the members of the church, the truth is that through love and unity, the members of the congregation of Hermosa Provincia were able to complete a beautiful temple to the greater glory of God,” replies Gutiérrez Avelar.

An EL PAÍS investigation published in September revealed that representatives of La Luz del Mundo in the United States requested a loan of hundreds of thousands of dollars from the Donald Trump Administration as a stimulus package to overcome the damage caused by the coronavirus pandemic. The non-recoverable money was released despite the fact that, according to people who have since left the church, the latter “does not pay salaries to or taxes on” members on the lower rungs of the hierarchy, or that member contributions have not stopped flowing in even after Naasón Joaquín was jailed. Asked about this matter, the church did not respond and merely said that its actions are “within the legal bounds.” It also denounced an attempt to “politicize” the support it has received.

Iván San Martín, a specialist in religious architecture at Mexico’s Autonomous University, believes that the temple’s pyramidal design is a metaphor for the hierarchy within the church and for spiritual ascension. The base, where most of the faithful stand, is wide. But the higher one climbs, the narrower it becomes. And at the very top, there is only one individual: the apostle. Ultimately, the pyramidal and palatial inclinations of the so-called “lineage selected by God” were reflected in other temples built by La Luz del Mundo, such as a pyramid with Maya-inspired motifs in San Pedro Sula (Honduras) and a replica of the Taj Mahal in Tapachula (in the Mexican state of Chiapas).

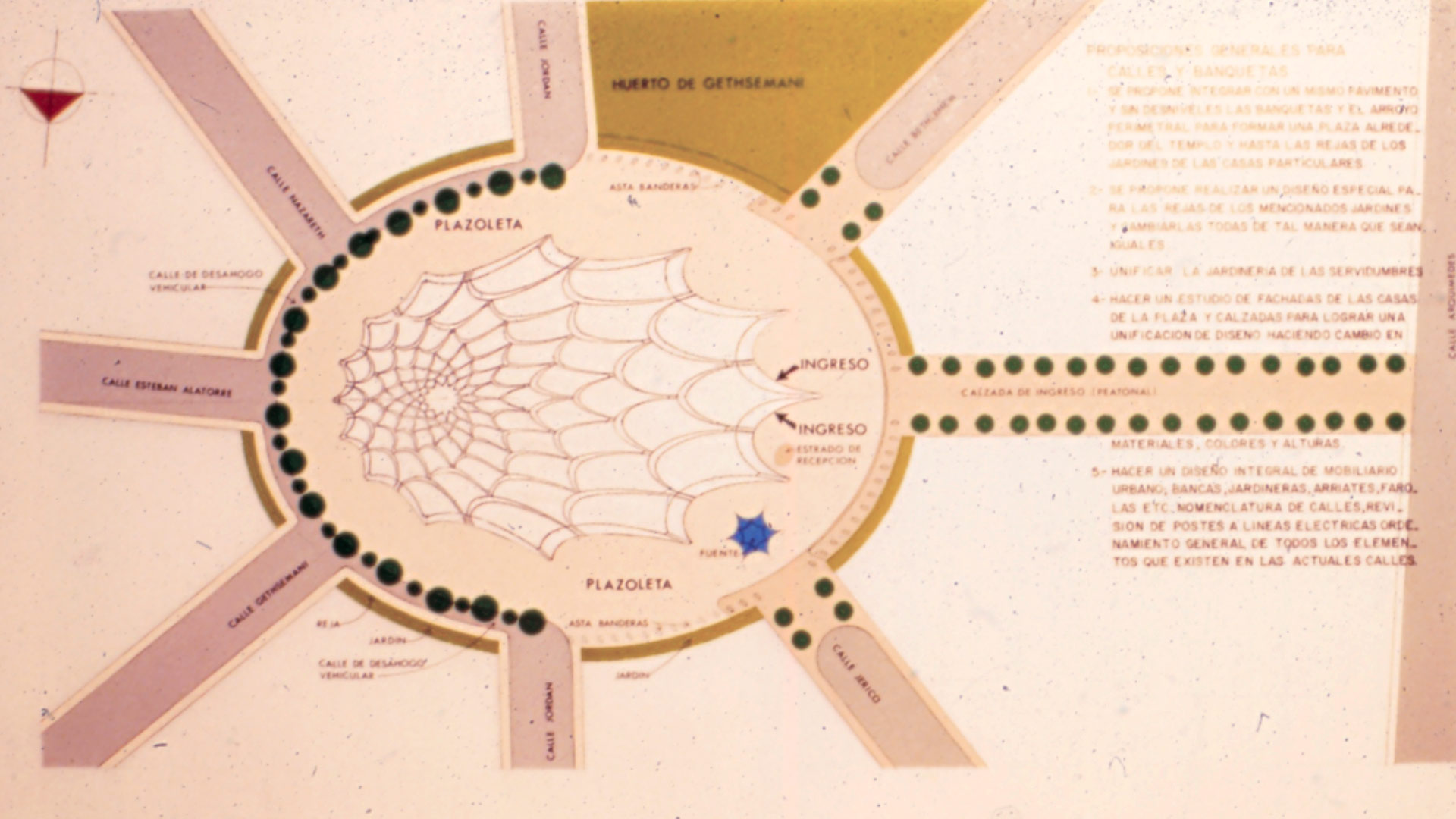

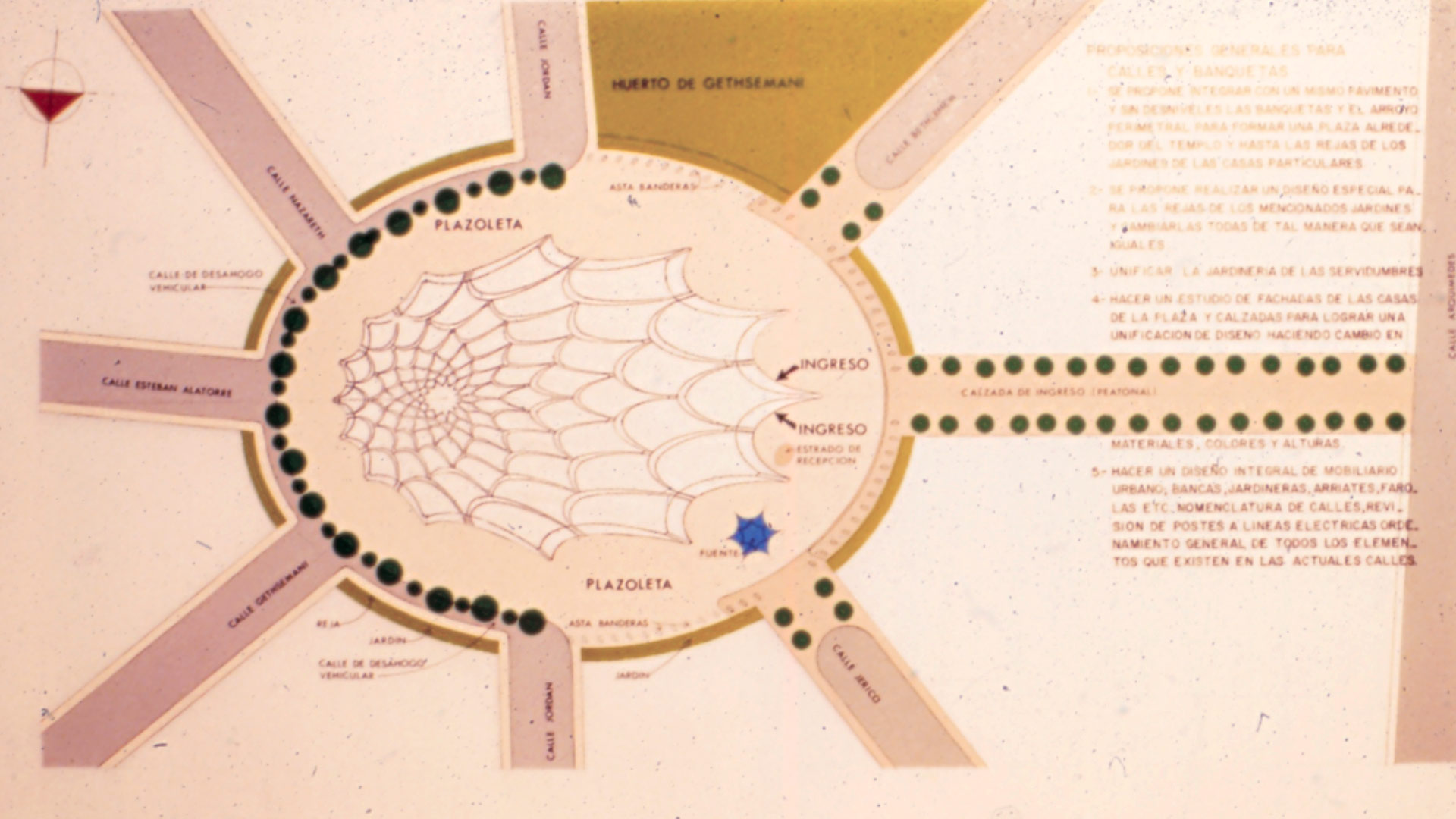

There is something else about the main temple that is peculiar. It is located square in the middle of Hermosa Provincia, and its elliptical base forms a roundabout with eight streets that open out to it, laid out diagonally. The colony has a panoptic layout, similar to a military citadel or an 18th-century penitentiary, with the temple towering over, and observing, everything that goes on around it, notes San Martín. Any reporter, intruder or curious onlooker will be immediately identified by church employees. “It’s not a coincidence,” says the scholar. “It is an expression of the church’s control over the earthly lives of its faithful.”

Underground

When Naasón Joaquín was arrested in L.A. and the charges against him began to emerge, the underbelly of Hermosa Provincia was also exposed: several media outlets published stories about the tunnels under the temple in Guadalajara. “The architecture of the church of Hermosa Provincia has been well documented for decades,” says Gutiérrez Avelar. “The insistence on asking this question only evidences a desire to present La Luz del Mundo as something secret or occult.”

It is common for centers of power with hierarchical structures to have underground channels allowing its leaders to move under the surface. A former collaborator of Samuel Joaquín who spoke with EL PAÍS on condition of anonymity says that Naasón’s father ordered a tunnel system built that would allow him to move between key spots of Hermosa Provincia far from the gaze of his followers.

According to this witness, the tunnel network had different access routes connecting, in one case, the apostle’s personal residence with the apostolic house, which served as one of his offices. From his desk, he could go down into a basement and walk down another tunnel to the back of the temple. From there, Samuel could look through a glass that was only visible on one side and observe what went on inside the meeting room for his ministers, who were in charge of running the church’s affairs. “He used to go there because it was important to watch that area,” said the source. “When somebody suggested installing a security camera, he said that he wanted to be there in case he heard something he didn’t like, so he could walk in and take charge of the situation.”

According to this source, the tunnel and passageway network had one main purpose: to serve as “escape routes.” Noting that this is not very different to what the headquarters of other religions do, the source adds: “Hermosa Provincia is a bunker.”

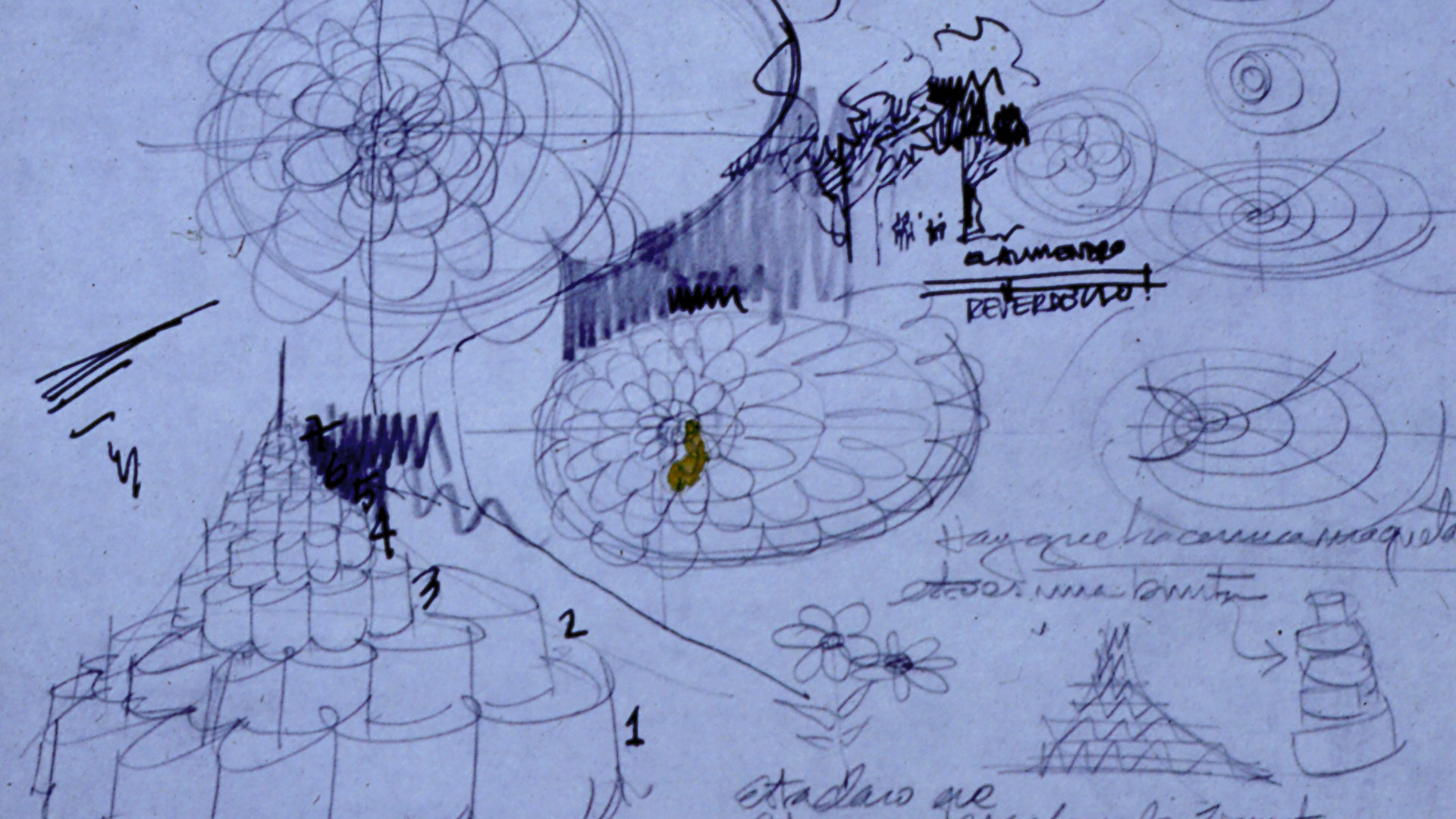

Sketch of the inside of the temple of Hermosa Provincia. CAROLINA MEJÍA

“Not just anyone could go into the tunnels. There were very few of us who had access,” said Sochil Martin, a former assistant who reported being physically and sexually abused by Samuel and Naasón Joaquín for 22 years, in an interview with EL PAÍS in early 2020.

“Hundreds, if not thousands of children have suffered the same fate as myself,” said Martin after filing civil charges against Naasón Joaquín in February of last year. Even before the latest scandal that is putting the current church leader on the stand, his father Samuel Joaquín had already been singled out by the media over sexual abuse in 1997. The main difference is that Samuel was denounced in Mexico, and Naasón in the United States. La Luz del Mundo holds that showcasing these accusations “is nothing more than an attempt to try the Apostle Naasón and our religious denomination in the media before the trial begins.”

Political and economic power

“In the 1990s, the relationship between La Luz del Mundo and the [then-ruling] Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) was extremely close. Those were days when the public prosecution office was basically in the employ of the executive,” says Masferrer. “If the political power said that accusations should not go through a judicial process, then no action was taken.”

After decades of nurturing its relationship with the PRI, the victory of the conservative National Action Party (PAN) in 2000 led La Luz del Mundo to diversify its political contacts. Guests at the celebration of the Holy Supper, one of the church’s most important annual rituals, have included Margarita Zavala, the wife of former president Felipe Calderón and herself an independent candidate in the 2018 election; Jaime Rodríguez Calderón, or El Bronco, another independent candidate at the last election, and Enrique Alfaro, former mayor of Guadalajara and current governor of the state of Jalisco with a party named Citizen Movement, to name a few.

The congregation’s political network spilled beyond the borders of Mexico: in April 2019 the church leader was honored with a resolution from the Senate of Texas “on the grand occasion of his 50th birthday,” just two months before his arrest in California. Following his arrest, Costa Rica lawmaker María Vita Monge, the first female member of La Luz to make it into Congress in her country, shared the following thoughts on social media: “It was he who taught me that ‘a good Christian is a good citizen,’ and I am fully confident that justice will be done.” The secretary of state for Honduras, Ebal Díaz, who has admitted that he is the pastor of “a small community,” was more cautious in his public statements about his faith following the arrest. And the church has a longstanding relationship with Nayib Bukele, the president of El Salvador, dating back to the days when he was the mayor of the capital (2015-2018). Despite the support that it has received, the religious organization says that it is, and always has been, apolitical.

“You don’t need this acknowledgment, but it is an honor for us to bestow it upon you,” said Bukele to Naasón Joaquín in 2015, after naming him “most distinguished son of San Salvador.” In May 2019, as president-elect, Bukele joined Joaquín in laying the cornerstone of Ciudad Luz del Mundo, a development project on more than 100 hectares of land near the international airport of San Salvador. And back in December 2014, when Samuel Joaquín died, the National Assembly of El Salvador observed a minute of silence. La Luz has followed a similar path in Nicaragua, where in 2017 it announced the construction of another “city” covering 30 hectares in Granada. And in the United States, the church purchased land in the city of Flowery Branch, in the outskirts of Atlanta (Georgia).

In Mexico, two members of the Chamber of Deputies came out in defense of their religious leader: Emmanuel Reyes, who ran with the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) but is now with the ruling Morena and Kehila Ku, of Citizen Movement. “If there is a bloc representing a church inside Mexico’s parliament, it is La Luz del Mundo. They are the sole confessional bloc,” says Masferrer. EL PAÍS sent interview requests to Reyes and to Israel Zamora, the first member of La Luz to reach the Mexican Senate, and allegedly the person behind the tribute to Joaquín held at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, but received no reply. Ku declined to talk to this newspaper, citing a busy agenda.

“It is a religious, political and business structure,” adds Masferrer. After the California Attorney General provided ample descriptions of Naasón Joaquín’s lavish lifestyle, Mexico’s Financial Intelligence Unit froze church accounts and assets worth nearly 390 million pesos (over $19 million) in March of last year. The announcement of economic sanctions was made as the Mexican Attorney General simultaneously announced a public investigation into human trafficking within the church.

By December, the office in charge of investigating financial crimes had filed five charges against La Luz del Mundo on suspicion of tax evasion, money laundering and irregular operations in tax havens. The church has replied that it is “fully disposed to clear up any misunderstanding.”

After a year-and-a-half behind bars, the future of Naasón Joaquín and of the church leadership is on hold. The pandemic has delayed the beginning of the final stages of the trial, a fact that has worn out both the defense and the witnesses. “We, just like the Apostle, are awaiting the day in court when these unfounded accusations will be confronted and their falsehood proven,” says La Luz del Mundo. After the case broke, the words “Honorable” and “Innocent” showed up in giant letters on the doors of the temple in Hermosa Provincia. But the battle cry has hit a wall of $90 million, the amount of bail set by a judge in California.

“I see the same techniques of permanent denial in the hierarchy, seeking to protect their source of income and manipulating the information that reaches the parishioners,” says the source who was once a part of the church’s top echelons. “It is difficult to pull out your roots because you are not just walking out on your religion, but also on your family. They view me as an apostate, an enemy.”

It is the same dilemma facing co-defendant Alondra Ocampo and her own relatives. “No matter how much evidence you show them, the parents and siblings of Alondra will always believe in the church, they are blinded by their faith,” says Thiagarajah. And as the trial proceeds, the line between accomplice and complainant is becoming increasingly blurred. “I don’t know where abuse ends and adult responsibility begins, although I can say that she is facing consequences for what she did,” admits the lawyer. After more than 80 years of scandals, these truths and responsibilities will be defined by the courts.

Credits

- Text: Elías Camhaji

- Edition: Eliezer Budasoff

- Audiovisual Edition: Héctor Guerrero | Gladys Serrano

- Design and Layout: Alfredo García

- Animation: Carolina Mejía

- English version: Heather Galloway and Susana Urra.