What will we do after the end of work?

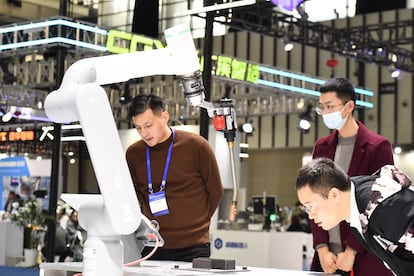

Automation and advances in artificial intelligence are posing the enormous challenge of a labor revolution in which machines threaten millions of jobs with obsolescence

In some factories, all work is done in the dark. There is no heating or air conditioning, because no machine has ever complained about the cold. Robots complete the entire production process, presaging a future of automation. “The factory of the future will have only two employees, a man and a dog,” quipped the American writer Warren Bennis, a pioneer in the field of business leadership, in his book On Becoming a Leader (1989). “The man will be there to feed the dog. The dog will be there to keep the man from touching the equipment.”

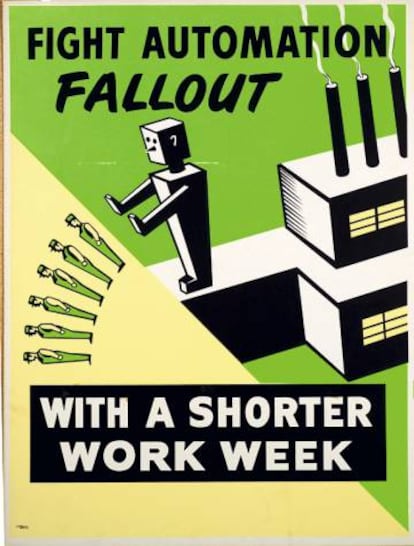

For decades, various theorists have anticipated the end of work, but never before have these predictions been so close to becoming reality, at least in some sectors. In 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted that, by 2030, the 40-hour workweek would be reduced to 15 hours as a result of technological progress. Jeremy Rifkin, in his book The End of Work, published in 1995, described a future where automation would lead to a marked decrease in the demand for labor, causing high unemployment rates. In November, Elon Musk, during a conversation with British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, predicted a scenario in which artificial intelligence could take over all tasks: “You can have a job if you wanted to have a job for personal satisfaction,” said the Tesla founder. “But the AI would be able to do everything.”

AI discussion with @RishiSunak

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) November 2, 2023

pic.twitter.com/f5FHGQzE4r

It remains to be seen whether these predictions will come true. All economic revolutions have entailed major reconfigurations of labor, but they have always created more jobs than they destroyed. Whether automation is temporary or permanent, the question nevertheless remains: What would millions of human beings pushed to the fringes of the labor market do with their time? Italian philosopher Maurizio Ferraris attempts to answer this question in his book Doc-Humanity (2022), where he argues that, in a future in which machines take over most productive tasks, human activities would be reoriented primarily toward one single outlet: the consumption of goods and services. “It is one of the few activities that a machine will never be able to perform, perhaps the only one,” he told EL PAÍS over email.

Ferraris highlights the importance of documenting and analyzing consumption patterns in a world dominated by automation. “In order to optimize machine production, it is essential to be able to understand and predict human consumption desires and behaviors,” he wrote. This analysis is made possible by collecting data and digital documents available on the web, which can capture and reflect the identities, desires and movements of individuals.

The Italian philosopher argues that, in reality, every time humans perform an activity on a digital platform, they are already working. This includes everyday online activities like scrolling through Instagram on the subway or watching a movie on Netflix. Digital companies and platforms collect this data and use it for a variety of purposes, such as analyzing behaviors and preferences in order to deliver personalized content, improve services, and deliver targeted advertising. Ferraris stresses the importance of consumers being aware that their online activity contributes to this process. He also suggests the possibility of establishing a universal basic income (UBI) financed by a tax on digital platforms that profits from the data produced by our interactions on the web.

Automation of routine jobs

Social concern about the disappearance of jobs has given rise to several reports, with disparate findings. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) estimated in July that 27% of jobs in advanced countries are at risk of automation. The Goldman Sachs Group projects that technological advances could mean the loss of 300 million jobs worldwide, or approximately 18% of the global workforce. The CEO of the multinational technology company IBM has warned that in 5 years, 30% of its workers could be replaced, and has currently paused hiring for certain positions. In Spain, McKinsey & Company forecasts that, by 2030, 1.6 million workers will have to change careers to avoid unemployment.

Moshe Vardi, Professor of Computer Science at Rice University in Houston, once predicted that in 30 years, most jobs would be done by robots and unemployment rates could exceed 50%. “Now I am less pessimistic,” he said in a telephone interview with EL PAÍS. Vardi foresees significant changes in the world of work, but doubts that all jobs can be automated. “The most vulnerable jobs are the routine ones, the ones that require repetitive and predictable tasks,” he explains, adding that jobs will only be automated if it becomes economically viable to do so: “For example, clearing a table in a restaurant is complicated for a robot and easy for a person, who will also do it for a low wage. So it’s unlikely that a restaurant would invest in such technology.”

Vardi points out that, historically, automation primarily affected manual or industrial, blue-collar jobs. Recently, however, with the advance of generative artificial intelligence, white-collar jobs, which encompass cognitive and administrative tasks, are also beginning to face the threat of automation. Although he acknowledges that new technology can create new jobs, Vardi has his doubts that the jobs lost will be balanced out by the jobs gained. “It’s also not clear to me that all workers with traditional skills will be able to adapt to roles that require more advanced training,” he says.

For Ferraris, a future where machines can surpass humans in complex creative tasks, such as writing novels, is out of the question. “It might write a sentence, a medical diagnosis or a law better than us, but always under human supervision. Also, only humans truly understand other humans and understand what can move them or make them laugh — an ability still unique to our species,” he says.

Even so, both thinkers envision a complicated transition period, marked by high unemployment rates and a growing need for worker training — a period during which the aforementioned universal basic income could offer a way to distribute the gains from the increase in productivity generated by artificial intelligence. The measure has prominent advocates, like Sam Altman and Elon Musk, the founders of OpenAI. Others, such as Nick Srnicek, one of the leading advocates of left-wing accelerationism, and the coauthor of Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work (2015), are more skeptical. “Not because I don’t like the idea, but because I believe that the circumstances of the contemporary world will not allow a meaningful UBI to emerge, for the time being. Our limited resources for political action are better spent elsewhere,” he told El PAÍS.

Srnicek points out that, in addition to the advance of automation, young people’s attitudes toward the importance traditionally placed on work are changing. “Younger generations are showing a significant rejection of the traditional work ethic and, in some cases we’re even seeing the emergence of anti-work movements like the Great Resignation [the millions of people around the world who left their jobs in the wake of the pandemic]. This shift in attitude indicates a desire to move away from conventional work structures, which would also require political and social changes,” he says. A Randstad report supports this observation, indicating that 58% of 18- to 24-year-olds would leave a job that does not ensure quality of life, while 38% have already left jobs because they did not match the needs of their personal lives. This contrasts sharply with the old saying: “There’s no bad job if there’s no better one.”

Spanish economist Lucía Velasco is among those who believe that, despite technological progress, “there will always be humans behind the machines.” Here, Velasco is referring to the millions of workers, often in precarious conditions in countries with fewer resources, who play essential roles for the functioning of AI, such as training the models for the technology. She argues that “a world without work is not possible, neither economically nor socially,” and that “work gives meaning and order to much of our lives, and by doing work, in most cases, citizens are contributing to the world.”

Velasco analyzes the impact of automation on the Spanish labor market in her book ¿Te va a sustituir un algoritmo? (2021), whose title translates as “Is an Algorithm Going to Replace You?” She suggests adopting a comprehensive approach that goes beyond retraining programs. “It’s important to have accurate data to understand how the labor market is evolving, and to consider the difficulties faced by workers, such as the lack of time for training,” she says. Recent studies on new foundational AI models indicate a productivity improvement of between 14% and 35%, says Velasco. “We must establish mechanisms so that the surplus generated by workers does not result in a reduction in wages.” In addition, she insists on focusing policies not only on improving digital skills, but also cognitive and transversal skills that are essential for developing and interacting with AI systems, as well as for algorithmic literacy, “to avoid being controlled by algorithms.”

One of the most complex challenges posed by a potential post-work world, says Srnicek, is assessing how the decline of traditional work would affect people’s identity and life purpose. While work provides benefits such as identity, culture, recognition, friendship, purpose and achievement, he says, these can be found more effectively outside the realm of salaried employment. “Work is actually a terrible means to achieve these benefits. It has become the default resource for them only because it takes up most of our time.” The Irish playwright Oscar Wilde, a keen observer of the society of his time, warned long ago of something similar in his short story, The Happy Prince: “Hard work is simply the refuge of people who have nothing whatever to do.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.