‘Nation shapers and culture makers’: A conversation with Alberto Ferreras

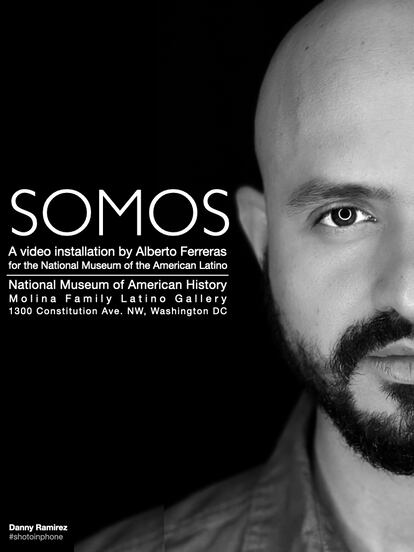

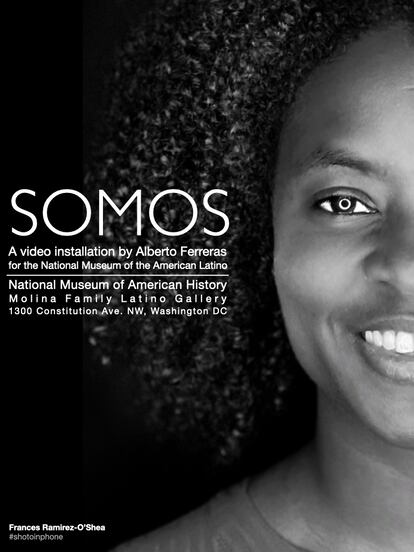

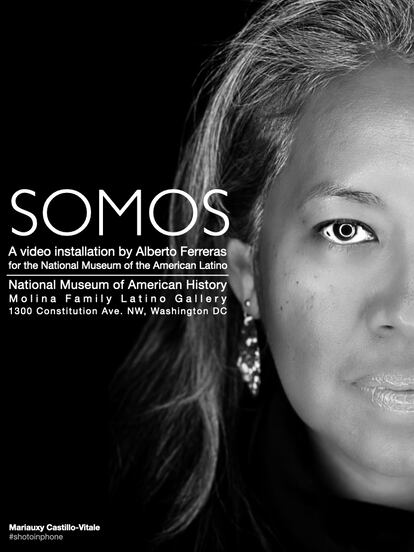

We talked about his video installation Somos (We Are), commissioned by the Smithsonian Latino Center, which was a central piece in the first exhibition of the new National Museum of the American Latino

Spanish-Venezuelan-American writer and filmmaker Alberto Ferreras is a natural storyteller propelled by the multimedia revolution who knows about the power of a face looking piercingly into the camera. He has been producing audiovisual content for more than 30 years at some of the most well-known American media emporiums for that mosaic of faces, origins, and identities that is the Hispanic community in the United States. One of his most recent works is the multimedia project Somos (We Are), a central piece in ¡Presente! A Latino History of the United States considered the inaugural exhibition of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Latino, still in the planning stages. It was inaugurated on June 18, 2022, during the launching of the Molina Family Latino Gallery at the National Museum of American History, which is part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, the world’s largest museum, education, and research complex.

Ferreras’s video installation was the first piece commissioned for the institution to be permanently showcased at their Somos Theater, featuring a mosaic of people of Hispanic descent discussing identity, family histories, and firsthand experiences. It is made up of 150 portraits of U.S. Latinos shot entirely on an iPhone, partially inspired by Ferreras’ series of photographic shots on iPhones of New York City during the Covid pandemic—some of them included in the exhibition Ciudades Durmientes (Sleeping Cities) at the Museum of Modern Art in Bogotá, Colombia.

“I think it’s really hard to do a description of the Latino community in sort of one sweeping statement,” says Chicano activist and artist Judy Baca in Somos’ promotional cut. “In and of itself, it’s a wonderfully diverse community, and I’m not sure non-Latinos actually realize that,” adds American engineer and astronaut Ellen Ochoa, the first Hispanic woman to go to space. Ferreras agrees, “The purpose was to make a video that discussed the phenomenon of Latino identity in the United States in all its complexity and diversity. We’re not a race. Hispanics come from all races, and there’s not just one-size-fits-all Latino experience,” he says.

“There were days when I took 60 portraits in one day,” explains Ferreras about the creative process. “And although the Hispanic community is portrayed in all its diversity, it does not try to meet quotas, which is something that scares me a lot when one approaches a group trying to characterize its members, because it is very reminiscent of the portraits of castes of colonial Spain, where the offspring of an indigenous and a white parent was called a mestizo, while the child of a mestizo woman and a Black man was a sambo. An entire demographic description that sought to create an ethnic hierarchy. On the contrary, this is a festival of countenances,” he says. “I want to highlight the role of language and facial expression in the common effort to understand each other.”

Ferreras is well-informed when it comes to multiculturalism. He is, after all, a Spaniard born in Madrid who emigrated as a teenager with his parents to Caracas, Venezuela. Later, upon graduating from the Andrés Bello Catholic University in Caracas, he earned a master’s degree in the United States and developed a thirty-year plus successful career in the media. “I was lucky that about six months after arriving, I had the opportunity to work for MTV, which had a program in Spanish.” It was 1991, and MTV was celebrating its tenth anniversary; Ferreras remembers it well because they had a private Prince concert, which seemed quite an extravagance back then. “I was there for two years working with Daisy Fuentes, who I adore, the anchor for a Latin music program called MTV International. My task was to find what this diverse audience throughout Latin America could like and what they had in common. And create that relaxed, youthful voice that was the hallmark of MTV.” Something that prepared him later to understand the composition of Hispanic immigration in the United States.

“There was a lot of prejudice then, and there still is with regard to speaking Spanish,” notes Ferreras. “One of the first mistakes that all immigrants make is thinking that because you speak Spanish fluently, you are better prepared than someone who has been here for many years or speaks Spanish as a heritage or home language.” Something that also happens to those who immediately disqualify an immigrant based on their fluency in another language.

“Since in Latin America, your social status is related to your ability to express yourself fluently, new immigrants tend to disqualify a person or discard someone who has more experience in this country than they do, but while not expressing themselves incorrectly, do it differently,” Ferrera remarks. He brings up a story that happened to him recently during an interview with a Hispanic descendant born and raised in Mission, Texas. “I am interested in all expressive phenomena, so I have been a fan of Spanglish for years,” Ferreras says. “But I had never heard the word ‘touchara,’ a conjugation of the English verb ‘touch’ like the Spanish ‘tocar.’”

“Some Hispanics think that because they speak Spanish very well, they will be the kings as soon as they get here. And that’s a fatal mistake that some have paid dearly,” warns Ferreras, laughing. “This is a misperception about the Latin experience in the U.S. that took me years to understand and reformulate.”

After MTV, Ferreras went to work at HBO when they opened a dubbing service for their programming called HBO en Español, a position he held for two years. Eventually, when his English improved, he did promos for Cinemax and HBO Main and stayed with HBO for twelve years. When HBO Latino was created, Ferreras moved to the new channel as a creative services executive producer, supervising the in-house production broadcast between films. “We had a series called Solo Leyendas, where we interviewed Mongo Santamaría, Johnny Pacheco, and all those amazing artists. One day, I convinced my boss to allow us to do a low-budget image campaign where we put Latinos in front of the camera on a white background to talk about the experience of Latinos in the United States. That’s the series called Habla (Speak).”

Habla was a 16 one-hour special produced by HBO between 2003 and 2022, winner of the Imagen, the Mosaic, the New York Film Festivals Awards, Promax and Mark Awards, and arguably one of HBO’s longest-running documentary series. “The idea of Habla came from Orson Welles. I watched a documentary about Welles in the 90s, which included material from a program he made in 1955 called Sketch Book. I was surprised that this son of a bitch, who was a genius, was able to stare straight into the camera and talk without screwing up non-stop for fifteen minutes. And I said to myself, ‘I’ve just spent fifteen minutes bolted to this seat, watching this man speak without blinking, telling a fascinating story.’ So, with Habla, I explored the possibility that someone looking directly at the camera in telling an audience a powerful story would be engaging enough.”

Ferreras is also the author of a novel, B as in Beauty (Hachette), and several short films: Verbal Sex (1999) and Tómbola (1997) premiered at the Berlinale, Bigger (2004) premiered at Outfest and presented at London’s BFI, and the Lessons series. He is also co-creator of the short-form bilingual animated children’s series El Perro y el Gato (The Dog and the Cat) for HBO Family (2004-2011), among other projects. But his most radical project yet about the experience of Latinos in the U.S. is perhaps his play Hamlet in Harlem.

“One of the best teachers I had in Venezuela was an Argentine immigrant, Juan Carlos Gené, a wonderful writer, director, actor. Gené is the author of a play called Golpes a mi Puerta (Knocks at My Door, 1994). In the first dramaturgy course, he asked us to write as an exercise a play that took place in the same place, without interruption or flashbacks. And I couldn’t do it. I feel like I spent 35 years with that issue pending, and finally, Hamlet in Harlem is what Gené asked me to do,” says Ferreras.

The comedy that takes place during the rehearsal of the staging of a New York and multicultural version of the play updates the conflicts. “The play focuses on satirizing and discussing the image of Latinos in the media, our rejection or acceptance of stereotypes, but there is something deeper that has to do with the father-son relationship, both in the protagonists and in the characters of the work, and both become intertwined,” warns Ferreras.

“What I like most about the play is that all the characters are wrong, and at the same time, they are all right,” he adds. “In Hamlet in Harlem, there is also something important from my learning as an immigrant. I feel that when you are a foreigner, you have the benefit of being much more observant of the differences, and you can create content about the society in which you have assimilated and say things that others are not saying just because you had to understand those dynamics to survive.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition