Enigmatic fairy circles detected in hundreds of arid areas of the planet

Spanish researchers have created a world atlas of the phenomenon, which has been found in 265 sites in 15 countries

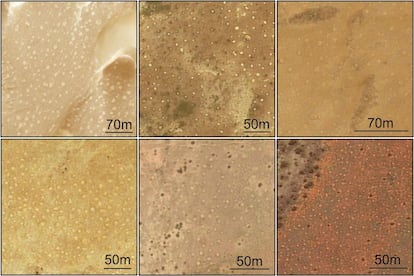

For decades, ecologists and botanists have been intrigued by a strange phenomenon. In several desert areas of Namibia, the little vegetation there is clears out, creating circular patches on the ground — patches that, seen from the air, appear to be organized into hexagons. These shapes are called fairy circles. A few years ago, very similar patterns were discovered in the Western Australian Desert, which added more intrigue to the matter. Now, Spanish researchers have complicated the mystery further by discovering dozens of additional examples of this plant distribution. These fairy circles all occur in arid areas where both water and nutrients are scarce. Circularity and hexagonal organization is the optimal way that plants have found to survive.

In 1971, the ecologist Ken Tinley observed in the coastal desert of the Namib (Namibia, Africa) circular patches of land barren of plants that were encircled by a ring of vegetation. They must have reminded him of fairy circles, a naturally occurring ring of mushrooms typically found in Europe, and he borrowed the name. According to many scientists who studied the pattern, fairy circles were the result of termites eating vegetation in the area. In 2017, Australian researchers discovered new fairy circles in the western desert. In their study of the phenomenon, the scientists ruled out the so-called “termite theory” and attributed the circles to mechanisms of biological self-organization, which had been previously explained by mathematician Alan Turing. However, that same year, other researchers — drawing on Aboriginal knowledge — linked the Australian fairy circles to another species of termites. The debate continues, and now new research from Spanish scientists is promising to make it even more heated. This team has found dozens of fairy circles across the globe.

On Monday, the scientific journal PNAS published the study, which was carried out by ecologists and soil scientists from the Complutense University of Madrid, University of Almería, University of Alicante, and Spain’s National Research Council (CSIC). This team created the first global atlas of fairy circles by feeding thousands of satellite images into an artificial intelligence (AI) system. This system was shown photographs of the circles in Namibia and Australia and asked to look for similar patterns. The AI spent a month scouring for patterns and presented its findings, which were reviewed by the researchers, who are experts in arid areas. The results were not what they expected: they found fairy circles in 265 sites in 15 countries on three continents. They also expanded the known number of fairy circles in the Namibian and Australian deserts and found similar formations in the countries that border the Sahara to the south, from the territory of Western Sahara to the Horn of Africa. What’s more, they also detected fairy circles in Madagascar, in southern and western Asia and in large quantities in central Australia.

“The ones we have seen have the same spatial distribution as those already known from Namibia and Australia,” said Emilio Guirado, from the Laboratory of Arid Zone Ecology and Global Change at the University of Alicante, who was the lead author of the study. One of the most intriguing features of fairy circles is that they form in near-uniform hexagonal patterns. The average fairy circle has 6.72 sides. After analyzing the new fairy circles, this number is almost identical: 6.71.

In a second part of the work, the researchers crossed-checked the results of the AI system with another AI program trained to study the environments and ecology of arid areas. The goal was to find out what factors facilitate the appearance of these patterns. “Our study provides evidence that fairy circles are far more common than previously thought, which has allowed us, for the first time, to globally understand the factors affecting their distribution,” said Manuel Delgado Baquerizo, leader of the IRNAS-CSIC BioFunLab and co-author of the study, in a press release.

According to the study, fairy circles appear in arid regions where the soil is mainly sandy. “Sand is very important. Where there is sand there can be fairy circles, but not in non-sandy areas,” explained Guirado. Other universal conditions include water scarcity, low rainfall and low nutrient content in the soil. “The vegetation breaks through differently than in areas where there are no water problems,” he added.

Regarding the role of termites, Guirado said that while they are found across the globe, “their global importance is low.” He added that they may play an important in some local cases, such as Namibia, “but there are other factors that are even more important.” It must be taken into account that the global atlas is a snapshot, a still image “which looks at whether or not there are fairy circles, but does not show anything about their origin or formation,” the scientist concluded. So it cannot be ruled out that insects played a role in forming the patterns. To clear up the mystery, the Spanish researchers believe more fieldwork is needed.

Norbert Jürgens is professor at the Institute of Plant Sciences and Microbiology at the University of Hamburg (Germany) and one of the leading experts on fairy circles. He has been studying the formations in Namibia for decades and supports the theory that they are due to the engineering role of termites. From Namib, he said that until the new patterns [detected by the Spanish researchers] are closely studied, “it would be useful for scientific debate to limit the term fairy circle to those structures first described by Tinley in 1971.″ He pointed out all arid zones reproduce patterns on the ground resulting from different processes, and questioned why “the methods applied by the authors found rounded, regularly spaced bare patches among the vegetation only in the Old World, not in America.” He added: “If this is correct, it would be a strong indication of the central role played by specific organisms such as, for example, termites, which evolved during evolution in Africa and Australia, but not in the Americas.”

Fernando Maestre, director of the Laboratory of Arid Zone Ecology and Global Change at the University of Almería, acknowledged that do not know why fairy circles were not found in the sandy deserts in the Americas. “We can only speculate,” he said. “It could be due to human action in the past, grazing, fires or changes in land use that reduced vegetation cover.”

What Maestre did highlight was the key role played by fairy circles in these extreme environments. The scientists verified that in areas where there are fairy circles, the primary productivity of the vegetation is greater. “These regular patterns increase the productivity of the vegetation, maximizing the capture of resources at a local scale. Primary productivity is an index that can be compared with the greenness of the plants, with their lushness. These are not orchards, but they do maintain that cover of life all year round.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.