Alcohol, fights and indestructible talent: How Peter O’Toole survived the bars

Ten years after his death, the legend of the British actor, who was capable of having the wildest night and then showing up on set first thing in the morning, remains alive

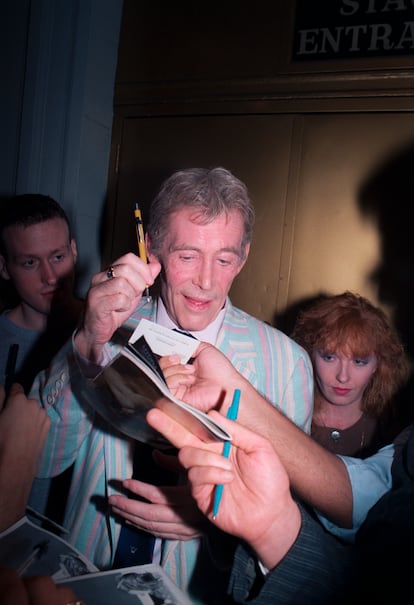

David Letterman’s Late Night show, May 1995. The host asks for applause for who he calls one of the all-time great actors. As the band plays the music of Lawrence of Arabia the camera focuses on the guest entrance, and in comes Peter O’Toole (Leeds, 1932-London, 2013) riding a camel. Suit made by the best tailor in London, French cigarette in a mouthpiece, exquisite British accent. Judging by his age — and especially by his appearance —getting down seems like a complicated task, so Letterman approaches with a ladder. O’Toole, however, smiles, dismounts with astonishing agility, opens a can of beer he was carrying in his jacket pocket and gives it to the animal, which empties it in one gulp.

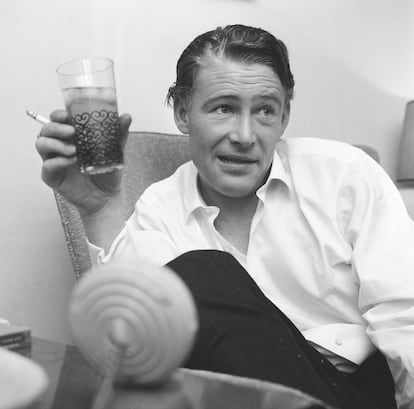

Those were years of reconciliation for an actor who usually shied away from interviews or, when it was impossible to avoid them, chose to sabotage them. The older viewers still remembered that first appearance on American television a few decades back, on Johnny Carson’s show. O’Toole had shown up so drunk that he barely lasted a couple of minutes; just enough to break his glasses, curse and run away. This time, however, with his sixtieth birthday in the rear-view mirror and unable to drink a single drop of alcohol, his life was very different.

For O’Toole, more than a calling, acting was an unavoidable path. He did not go to school until he was eleven years old, and he did not last long there. He was expelled from the Navy for mental incompetence. Journalism was a fleeting adventure from which he quickly fled. But the poison of the theater was inside him since he was a child, and he went for it desperately, all in, like everything he did in his life. One day he knocked on the door of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and confirmed what he already suspected: that the technique he had instinctively developed put him light years ahead of any of his colleagues.

By the time he was twenty, O’Toole was leading the cast of the renowned Bristol Old Vic theatre, and at twenty-six he was the star of the Royal Shakespeare Company, the most prestigious in England. There, he would leave a Hamlet that the chronicles still remember to this day and that made him the visible head of a revolution that was reinventing the post-war British theater with a handful of young actors with enormous talent and class pride that also included Richard Harris, Michael Caine and Richard Burton. None of them wanted stardom; their aspiration was to make acting the full experience of their lives.

Those in charge of the company did not take long to connect the bell that announced the beginning of the performances with the telephone of the corner pub. That was the only way to guarantee the punctuality of their main actor, who had decided to spend there any minute that he had to be off stage. Because O’Toole liked the theater, and he also liked to drink. And don’t bother trying to find any troubled reasons for it, either, because there were no childhood traumas or personal dramas to drown in that booze: he just liked to do it because it was fun, because it provided him with an endless stream of anecdotes, because it was a way to extend the nights with his companions and friends.

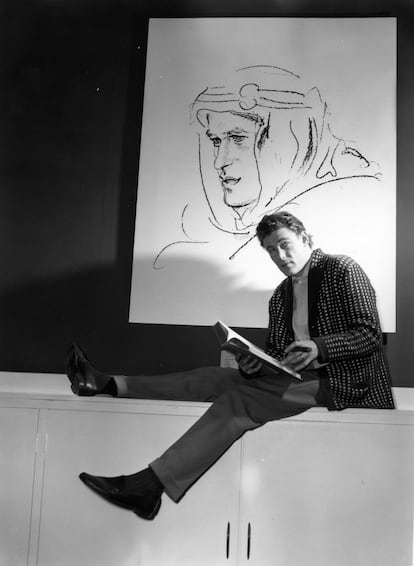

England was beginning to become too small for the actor’s growing prestige. The leap to global stardom came through two twists of fate: the first was when he turned down Elizabeth Taylor’s offer to play Mark Antony in Cleopatra (faced with his refusal, the actress turned to Richard Burton and another legend was born). The second was another withdrawal: that of Marlon Brando from the lead role of Lawrence of Arabia. Suddenly, O’Toole became part of the greatest film in the history of cinema.

It was a long, complicated shoot. O’Toole suffered third-degree burns, dislocations, sprains, bruises, broken bones and even a deviated spine. But his work was so extraordinary that it began to overshadow that of the highly renowned Alec Guinness and Anthony Quinn. His sympathy, however, was aimed at another unknown actor at that time. His name was Omar Shariff and they would rush to the airport together as soon as a few days of rest were available, usually headed for Beirut, where they would party the night away at every joint they could find. But it could also be New York, where they went to meet comedian Lenny Bruce and ended the night behind bars with him.

Despite so much coming and going, not for a single day did O’Toole fail to perform in front of the cameras. Actress Siân Phillips, who after marrying him lived besieged by an avalanche of crashed cars, calls from the police in the small hours of the morning and sudden disappearances that sometimes lasted days, used to tell anyone who would listen about how hard it was to live with a man who was professional to the point of asceticism when he had to work on a character, and deranged to the extreme when he had nothing to do. After two years of filming, the opening night of Lawrence of Arabia was shaping up to be the most important of O’Toole’s professional life. He arrived at the theater drunk. But no one cared: that canonical performance in that canonical film earned him his first Oscar nomination and an aura of respect that few actors had known until then.

Of course, O’Toole would find out about all this years later, because the leap into the major league of his trade came accompanied by a plunge into the major league of partying; he would later confess that he was able to recall how the decade began and how it ended but, unfortunately, nothing in between. Not that there was nothing worthy of remembering: films as notable as Becket (1964), cult films such as his tribute to Dylan Thomas, Under Milk Wood (1972), more Oscar nominations, Shakespeare productions that overshadowed the memory of Laurence Olivier, as well as others by Bertolt Brecht that ended in monumental failures. Not to mention all the conflicts: arrests in several continents, a narrow escape from being massacred by a Khmer Rouge commando while filming Lord Jim (1965), whiskey breakfasts with John Huston while shooting The Bible (1966), or fistfights that could break out in places like a Parisian restaurant or on Via Veneto, after catching some paparazzi taking pictures of him with Barbara Steele. The actor did not seem to know any limits, and the shootings became an incessant struggle to contain him.

During the production of The Ruling Class (1972), the Twickenham studios executives decided to set up his own bar in an attempt to keep him under control after seeing him on television at the local racetrack, glass of whiskey in his hand, five minutes after he had announced that he was going to the dressing room for a moment to go over his role.

It seemed that his social life would put an end to his career sooner rather than later, but that never happened. His professionalism remained unyielding and his performances memorable. The people that worked with him adored him for his quick, boundless wit and his sense of humor, which could take on anything. Even someone as restrained as Audrey Hepburn sought his company, despite the fact that after their first encounter she returned so drunk to the studio where they were filming How to Steal a Million (1966) that she crashed her car into the lighting equipment. Whenever O’Toole lost control, she resorted to anything that would get him back on track, no matter how drastic. “I knew Katharine Hepburn loved me when she punched me,” he confessed.

The spark began to smoke in the mid-1970s. Siân, who had just gained financial independence thanks to her participation in the BBC series I, Claudius (1976), left him after finding out that he had bought a mansion in Puerto Vallarta and was living there with a Mexican woman twenty years his junior. By then, family life was a complete disaster: when his little daughter fell ill, O’Toole went to see her in the hospital and she asked her mother who that nice man was. But none of that was a source of drama for the actor. His real problem was that after a recent visit to the doctor that had resulted in an emergency operation, the doctors had strictly forbidden him to drink. His level of alcoholism was such, that just one more drink could kill him.

Approaching fifty, O’Toole understood that it was the beginning of a second chapter of his life — one that still revolved around the pubs, even if his glass was full of lemonade instead of whiskey. Sober people were not for him. Going back to work, however, did not seem like an easy task. When the actor saw that Caligula (1979), his great return to the screen, went from being a serious film with a script by Gore Vidal to being a pornographic movie due to the addition of explicit material, he knew that his moment had passed. A new generation of American actors led by Robert De Niro and Al Pacino had surpassed his, and the roles stopped rolling in. He did not worry: he still had the theater, where he knew that his figure was still surrounded by a mythical aura. Two decades later, in 1980, he returned to the Old Vic to do a Macbeth that became a true popular phenomenon.

But the big screen did not forget about him. Maybe it was through comedies that nobody found funny, regrettable self-parodying roles or even embarrassing superhero movies — one needs but to look at his participation in Supergirl (1984) — but O’Toole was clear that the results of the films were not his problem, and he knew how to find worthy acting challenges: his role in The Last Emperor (1987) propelled him back to the top. The years had not appeased his irreducible spirit. O’Toole was just as capable of participating in a blockbuster like Troy (2004) as he was of leaving the premiere after only watching 15 minutes, referring to the movie as “a disaster.”

Those might not have been the most brilliant years of his career, but the actor knew that there was still some fight left in him: when in 2002 the Academy presented him with an honorary Oscar for his entire career he protested, because, he claimed, it was not over yet. And he was right: in 2006, at 75 years old, he would still get one last nomination (for Venus). It was his eighth, and he left empty-handed again, a record that only Glenn Close has equaled to this day.

O’Toole announced his retirement in 2012. He knew that the time allowed by that stomach cancer detected four decades earlier was running out. Death would finally come on December 14, 2013.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.