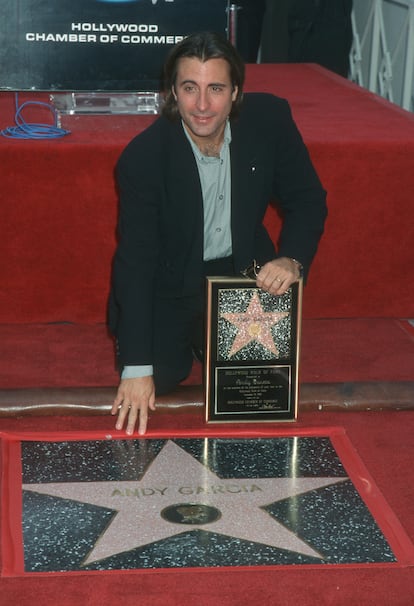

Andy García, the Latino who could have reigned in Hollywood

A recurring figure in the films of Coppola and De Palma, the Cuban built a career that paved the way for others who came from abroad. He now prepares for the release of ‘The Expendables 4′

At the beginning of Andy García’s career, a casting director wanted to check if the actor was strong enough for a role. He asked García to take off his shirt. “You take it off first,” the actor responded before leaving the room. Had he been an actress, this would have spelled the end of his career, but a man can afford to defend his integrity without fear of reprisals. García had the opportunity to develop a career in which he has remained faithful to his principles without ever exposing his body or starring in sex scenes. “I don’t want to go down that path,” he told journalist Mónica Garza. Still, he has become a sex symbol despite himself.

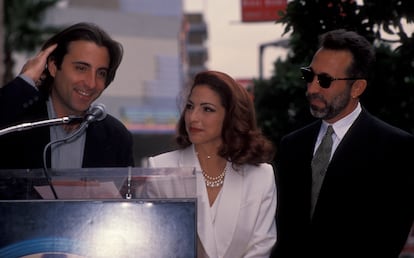

In the mid-eighties, García was predicted to have a career similar to that of Robert De Niro. 40 years later, however, the prophecy has been unfulfilled. Despite his status as an actor courted by Coppola and De Palma, in recent years he has found himself involved in projects that minimize his talent, diluted in ensemble casts. Proof of this decline is that some of the highest-grossing projects in which the star has been involved since the Ocean’s Eleven trilogy (2001-2008), are Geostorm (2017) and Beverly Hills Chihuahua (2008). His most critically acclaimed recent role is a Latin version of Father of the Bride with Gloria Estefan (premiered on HBO Max) where he showed off an unusual comedic side. This year, Garcia premieres the fourth installment of The Expendables, the new adventures of the band of old glories of action cinema headed by Sylvester Stallone.

Just some years ago, Garcia was the most relevant Latin actor since Anthony Quinn. For a decade, he maintained a perfect balance between independent films and popular cinema. But his career didn’t take off. “He has all the smoldering Latin volatility, the darkly dangerous good looks. Why didn’t he become the next De Niro or Pacino?” asked The Guardian.

Not even to buy cigars

Andrés Arturo García Menéndez, his full name, was 5 years old when his family left Cuba and took refuge in the United States, as a result of the revolution against the dictator Fulgencio Batista and the rise of Fidel Castro. His mother was an English teacher and his father a prestigious lawyer who owned an avocado plantation in the municipality of Bejucal. That privileged property and a house facing the sea in an exclusive neighborhood of Havana were the scene of his childhood, until he abruptly found himself living with his parents, siblings, and grandmother in a one-room house. The once-wealthy family arrived in Miami Beach with just $300 and a box of cigars. They started from scratch.

“That first Christmas we didn’t even have enough money to buy gifts for the children,” confessed the actor’s mother, Amelie García. “But the children never heard us complain about what we had lost, only about our longing to return.” That constant desire in the actor’s life has been reflected in his projects as a director, from Guillermo Cabrera Infante’s script The Lost City (2005) — a long-cherished project that featured Inés Sastre, Bill Murray and Dustin Hoffman, a love song to his longed-for Cuba — to the documentary Cachao (Como su Ritmo No Hay Dos) (1993), about the emigrated Cuban musician.

García’s first passion in the United States was basketball, which he intended to pursue professionally until acute hepatitis derived from mononucleosis kept him benched for a year. He ended up opting for acting, although his father preferred him to run the family business. “My father had no concept of the entertainment business or acting. To him, an actor was Humphrey Bogart or Clark Gable. I’m sure in the back of his mind he said, ‘I love my son, but he’s no Humphrey Bogart,’” he joked in The New York Times. Luck came to him in the form of a small role in the pilot of Hill Street Blues (1981), Steven Bochco’s masterpiece that changed police series forever.

If newly minted stars like Pedro Pascal still recall the difficulties of escaping the cliché of the Latino criminal, we can imagine what this meant in the eighties. Andy García not only did not want to be a stereotype. He did not want to be pigeonholed. “When I started, they only offered me gang members. I told the casting directors: ‘I didn’t study Latin acting, I studied Shakespeare and Tennessee Williams,’” he declared during a tribute to his career held last year at the Red Sea Film Festival in Saudi Arabia.

After seeing him as the villain in Eight Million Ways to Die (1986), Brian de Palma tapped him to play Frank Nitti, the elegant hitman from The Untouchables (1987) who, in a nod to Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), ends up flying in one of the most iconic sequences of the film. “He was mean, tough, and cunning. We thought [when we saw Eight Million]: ‘Wow, what a great killer!’” Producer Art Linson told People. But García wanted a juicier role on the other side of the law. “I told him I wanted to play a police officer, and he looked at me like I was a Martian.” He aspired to be like George Stone, the marksman of Italian descent, and he achieved it. De Palma’s film earned four Oscar nominations, critical applause and considerable box office earnings. From a legendary filmmaker and the mafia, he went on to another renowned author, Ridley Scott, to play Yakuza in Black Rain (1989), another popular success. Then he went on to play Richard Gere’s antagonist in Internal Affairs (1990), a character written expressly for him. While he prepared, however, another Italian role came to him that was going to change his life. García came to the cinema when no one was talking about cultural appropriation. If Natalie Wood, of Russian origin, could play the Puerto Rican Maria and John Wayne had been Genghis Khan, why wouldn’t a Cuban be the Corleone heir?

When it began to be rumored that Francis Ford Coppola was preparing The Godfather: Part III (1990), half of Hollywood tried to sneak into it. Garcia pressured his agent and ended up competing with Alec Baldwin, Val Kilmer and Charlie Sheen for the role of Vincent Mancini, Michael Corleone’s impetuous nephew, the titular heir not only to a mafia empire, but perhaps even to a future fourth installment.

He got his first and only Oscar nomination thanks to that performance, but the film was not the phenomenon that was expected. When it was released, it failed to displace Home Alone (1990) from first place at the box office, and the reviews were not flattering. It didn’t help that Winona Ryder withdrew from the project at the last minute and her character, that of Mary Corleone, Michael’s daughter and romantic interest of García’s character, fell to the inexperienced Sofia Coppola, the director’s daughter.

After working with the top directors of the moment, García was a star, but the definitive push was missing. He appeared in Dead Again (1991), the supernatural thriller by Kenneth Branagh, and the comedy Hero, by Stephen Frears, films that were well received but failed to move his career forward. Above all, he opted for too many failed projects: the cliché-filled thriller Jennifer 8 (1992); the romantic drama When a Man Loves a Woman (1994), where he was the devoted husband of an alcoholic woman played by Meg Ryan at a time when no one wanted to see America’s Smile drunk and hitting her daughter; and Things to Do in Denver When You’re Dead (1995), a little noir gem that could have been a classic but no one knew how to sell it. He headlined posters and his Latin identity was irrelevant in the scripts, but his career entered a coma from which he was only rescued by Soderbergh in Ocean’s Eleven.

García is aware that he may have a difficult personality. “By my very nature, I tend to feel comfortable swimming a little against the current,” he said. Religious and politically conservative, in 2010 he told El País Semanal: “How many times have I heard from producers that ‘Andy, sex sells!’. I don’t doubt it, but sell it to someone else.” Another reason for his reluctance to engage in sexual scenes is that he believes they imply a lack of respect for his wife, María Victoria Lorido, whom he met in 1975, the same day he asked for her hand. “We were very young, but she swept me off my feet. Some people know each other a while and there’s a friendship first, but when we met that night, it was very clear that this was the woman of my life,” he told People. “I didn’t want her to escape.” Seven years later they married, have four children and form one of the strongest couples in Hollywood. “Marriage is like a religion, and should be treated as such,” he says. The family, he says, is the center of his life and that has led him to lose roles. If a project made it difficult for him to be with his children, he rejected it: “I am a father and that is my priority.”

That firmness was evident in a curious controversy with Antonio Banderas that elapsed in the pages of this newspaper in the early nineties. The man from Malaga made a statement to El País Semanal in which he stated that García was an emigrant “who doesn’t want to be an emigrant, he wants to be an American.” The words reached García’s ears and were distorted by Guillermo Cabrera Infante. In a letter to the director, the writer reminded Banderas that his first big role in Hollywood, The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love (1992), had come to him after García’s refusal to appear in the film — something that happened again in Two Much (1995), in this case due to a question of dates —, although the main reason for his anger was that Banderas called him an emigrant and not an exile.

Banderas apologized in another open letter, praised the actor (“one of the greatest supporters of Latin culture through his work and his private life, both inside and outside the United States”) and expressed his desire to work together one day. It hasn’t happened yet, but both kings of mambo still have a long career ahead of them.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.