The not-so-innocent tan: A bronzing that speaks of the economy and social status

Not everything skin-deep is superficial — certainly, not tanning. The impulse to darken our skin has deep roots in history, and speaks to our relationship with the sun, a bond marked by philia and phobia, fear and veneration

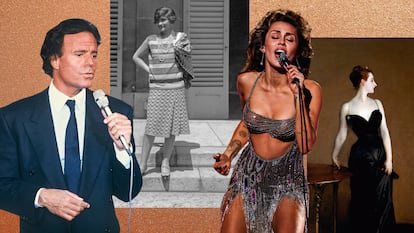

Welcome to the history of the tan, a story full of comings and goings, today “I love you”, tomorrow “I hate you”. In its telling appear Coco Chanel, Julio Iglesias and Miley Cyrus. We also have here an attempt to answer a key question: after years of demonizing the sun, is being tan coming back into style, and our good graces? The answer is a resounding yes if you’ve been paying attention to your screens, which these days is akin to paying attention to the world around you. We see that, since 2017, Google searches for the words “self-tanner” and “glow” have increased; so have those for sunscreen. This has less to do with white people having skin like a person in a Martin Parr photo as being “sun-kissed”, a much more literary term whose hashtag yields thousands of results. Neither is this, really, about sun bathing, but instead, the replication of its effects on our skin.

Color suggests health and health is beauty. The term “self-tanner” has taken over TikTok, and thus, our brains. Cyrus appeared to glow at the Grammys, shining her star power across the world: the singer is an investor in the self-tanning brand Dolce Glow. The sun care and tanning products category is gaining shelf space in stores and being spotlighted by brands: yesterday’s self-tan stigma appears to have faded away. Cult Beauty, a leading online cosmetics store, has assigned such creams and sprays the same level of importance as facial and body products. And we’re not talking about products that you put on before heading out into the sun, but those you use to achieve a golden sheen, which is quite different. Such is the sun scene in 2024, but let’s begin our tale at the beginning, far back into the past.

A complex tale of tanning

The sun has been performing its function for 4.6 billion years. Nonetheless, intentional and fashionable tanning is a recent invention. We’ve only been doing it for 100 years. Up until the beginning of the 20th century, no one was talking about ultraviolet radiation. But it was certainly taking place, and in many Western cultures, people didn’t like it. It’s clear that the color of our skin has never been an innocent matter: in ancient Greece and Rome, people used certain substances, at-times poisonous, to lighten their epidermis. The custom has lasted through the ages. Pascal Ory, in the book L’Invention du Bronzage, speaks of an epidermal Ancien Régime in which pallor underscored elite lineage. According to the French historian, this way of thinking sprang up during the early Christian era, when whiteness was associated with innocence and virginity. Dark-colored skin was linked with opposing concepts: vice and, moreover, everything foreign and colonized. Intellectualized or not, the truth is, tanning has always been a sign of status, it’s just that what status it entails tends to vary with the times.

To obtain clearer and lighter skin, people have committed extreme acts throughout history. Michael Jackson comes to mind. Boomers will recall how the pop star, who allegedly had vitiligo, a skin condition that causes pigment to become blotchy and sometimes leads affected people to attempt to even out their tone, was found to have skin lightening cream in his home at the time of his death. Such measures pale to those carried out by Elizabeth I of England, who reigned during the 14th century. She destroyed her skin, as did many upper-class women of the time, by applying ceruse, a lead-laden compound, in order to appear white as a sheet. The mistreatment got so bad that eventually, she stopped posing for royal portraits. Her story appears in The Ugly History of Beautiful Things by Katy Kelleher (Simon & Schuster, 2023), which reflects on the paradox of loving beauty within the capitalist system. According to the journalist, many of the aesthetic gestures in which we take refuge contain their own ugliness, and that letting the sun roast us is but one example.

Traveling into the future, we arrive at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, a turning point in the history of tanning. In the middle of the 19th century, England’s beloved white skin began to lose ground to the bronzed look. The reason for this is clear: factory workers moved from the countryside to the city, where they spent their days laboring indoors; therefore, the upper classes became the ones who could enjoy the outdoors and the rays of the sun. People tanned because they could.

But the trend did not last long. Once again, the ideal turned over (this is a story of many flips, like a vacationer in a deck chair) and during the rest of the 19th century, the sun once again became the foe of the elite. This is the era in which we saw ladies perambulating with parasols and sun hats. The works of Sorolla illustrate the phenomenon, that of women who stroll along the beach covered from head to toe, or Singer Sargent’s Portrait of Madame X, in which Viginie Amélie’s porcelain skin gleams. The upper class didn’t work outside and its women, less so, and they wanted to make that fact clear. According to Ory, men, who tended to spend more time outside, were attracted to pale-skinned women, who were considered “as valuable treasures, external signs of wealth, superiority and, in that sense, kept from the reach of other males as well as from the sun.” Societal trends are never unaccompanied by gender tropes.

Such ideals reigned for years, until the arrival of the 20th century and with it, the medical field’s belief that exposure to the sun had many benefits: healing skin ulcers, strengthening bones, etc. Niels Finsen emerged as a defender of so-called phototherapy, and told the world that the sun was a source of health; indeed, he was awarded the Nobel Prize of Medicine for espousing such tenets. And so, the sun became therapeutic — but it took Coco Chanel to make it fashionable. In 1923, the style legend caused a ruckus when she disembarked from a boat in Cannes with a sunburn. But, according to Chanel expert Inmaculada Urrea, the designer had already been a fan of sunbathing for years at that point. There is a photograph of Chanel lying on the beach from back in 1918. Urrea reflects: “In the 1920s, her celebrity was consolidated. Everything she did became fashionable. It was the decade in which she first appeared in casual pearls, which contrasted with her tan. She was the first worldwide influencer.” The expert offers another interesting notion: “She was a peasant who reached the world of luxury, but she carried out her own revenge. Her clients, who were wealthy people who had never dared to be tan so as not to look like they looked in the fields, ended up coveting her tanned skin.” Chanel was not the only one responsible for the rise of tanning. The growing popularity of sports also helped, as did the advent of paid vacations, the incipient democratization of travel and the evolution of swimwear, to which Chanel also contributed. In the end, it seems, she invented nearly everything.

Starting in the 1920s and lasting through to the ‘90s, with the exception of the two world wars, during which Europe was mainly concerned with survival, the Western world wanted to be tan. The reasons were obvious: only those who got vacations could sun themselves. Who didn’t want to be among those numbers? Dark skin (on white people) was aspirational, a word that had yet to be assigned to advertisements at the time.

The first tanning products were launched in the opening decades of the 20th century. And once again, Chanel was on the cutting edge. In 1927, she launched Huile Tan, a tanning oil whose slogan read: “Bronze skin and protected from sunburn”. Around the same time, Jean Patou jumped on the train and launched his own tanning oil, Huile de Chaldee, which was sold in a glass Baccarat bottle. It was not suitable to all salaries, which had the effect of elevating the status of the tan. Years later in 1935, Eugène Schueller launched a more accessible product: a bronzer with solar filter under the name Ambre Solaire. This was the era during which Scott Fitzgerald, in Tender is the Night, wrote of brown and fabulous characters.

When World War II ended, the tan began its golden era, if you’ll pardon the pun, driven by doctors’ recommendations, the rise of fresh-air sports, surfing and the chance to travel to warm destinations perfect for experiencing the life of leisure from a deck chair. Let’s make note of 1953, the year of what is perhaps the most famous ad for tanning of all time: the cheeky Coppertone girl. The memorable illustration was created by Joyce Ballantyne and in its live-action version, its young sprite was played by none other than Jodie Foster. The campaign suggested that tanning was for the whole family, and in places like Spain, that fact was apparent: in the ‘50s, the economic institution of sun and beach was being forged, and would later explode in the ‘60s. The history of tanning for tanning’s sake runs parallel to that of travel. Along the way, the pair found a friend in color photography. This was also around the time that Hollywood began to shine in Technicolor, its stars’ skin looking even more lustrous when they sported a golden tan.

Eventually, this sun would set. Solar rays were found to damage the skin, and it became important to protect oneself from their threat. The concept of SPF (sun protection factor) first appeared in 1962. No one, save for doctors, initially paid it any mind. Dr. Jorge Arroyo, a dermatologist at Madrid’s Dr. Morales Raya Clinic, says: “Tanning is the skin’s response to damage produced by ultraviolet radiation. Although it has traditionally been associated with beauty and healthy living, in reality it is a sign that skin has been submitted to the ‘attack’ of radiation, and appears to have defended itself from this attack.” But those were still the years of the blue Nivea jar: one had to be tan, and one had to maintain the color. It was known that the sun could burn you, but it still wasn’t an enemy. And society was learning that the star that raged 93 million miles above our heads was no longer a necessary partner in being tan. Tanning beds were invented in the 1970s, a boon to those who could not travel and who did not have the sun’s glow on-hand at all times. The ‘80s and ‘90s became the glory days of tanning: the damage they caused was roundly ignored (or at least, people tried to ignore it). UVA ray businesses popped up throughout urban areas, as famously documented by American Psycho. You couldn’t succeed in business with pale skin. In 1984, Guerlain launched its Terracotta powders, and their low-cost alternative by the Spanish brand Nilo made their way into the toiletries of many of the country’s women who couldn’t tan all year round, and perhaps did not want to, anyway. Proof of this era can be found in the photographs of Gunilla von Bismarck and her friends partying in Marsella with luminescent skin, not to mention images of Julio Iglesias, who built an entire identity around his tan, and the princesses of Monaco on their eternal, golden vacation. In 1989, the woman who would be queen, Isabel Sartorius, popped onto the collective conscious in her Mickey Mouse swimsuit and deeply tanned skin. Spain was euphoric, and the feeling was translated in lustrous, refulgent looks symptomatic of an irresponsible nation and its skincare practices.

But no party, not even those of the Marbella Club or Mayte Commodore, lasts forever. With the dawn of the new century came a growing sense of trepidation. And here, the trend turned over once again: we went from loving the sun to despising it. In the 2000s, we learned words like “melanoma” and “carcinoma” and other, milder terms like “spots”, and all were dangerous. The sun was demonized and tanning oils turned to sunscreens. The acronym SPF crept into the cosmetic conversation. Those who sunbathed would cop to it only in whispers, and always with an accompanying “but I use SPF 50.” You had to be living in a cave not to know that reckless sunning could cause serious damage to your health. We ventured upon the expression “healthy tanning” and put it to use summer after summer, even though Arroyo clarifies: “There is no such thing as a healthy tan.”

And now? We are well aware that we can opt for bronze with or without the sun. 90% of ever-so-necessary Vitamin D comes from solar exposure, but don’t fret: experts say that only 10 minutes without sunscreen are necessary during the summer to obtain its benefits. Cosmetics, once again, have come to the rescue, and it’s easy to find the products you need to be both tan and healthy. After all, brands are investing millions in their development. Nowadays, we have self-tanning drops, mousses, serums, color creams, all to achieve that “sun-kissed” effect.

More indications of the dynamism in the sun products sector: Sofía Vergara joined Spain’s Cantabria Labs in 2021 for the launch of Toty, a brand of sun protection. Cosmetic trends like “latte makeup” demand tan skin every day of the year. The latest generation of self-tanners will never leave you Trump-orange, dry in streaks or smell bad: nowadays, they take the form of drops that can be added to lotions or creams that gradually change skin tone application by application. Queen Letizia of Spain proudly sports her year-round tan, regardless of whether it came from the sun’s rays or a bottle. The desire to be bronzed “can be related to self-image or self-esteem, because many people see that a darker shade of skin improves their appearance and self-confidence,” says Gonzalo Jiménez Cabré, clinical psychologist for GrupoLaberinto. He adds: “Additionally, a tan can cover up imperfections in the skin, which reinforces its visual appeal.” Isn’t that a goal shared by royalty, stars and everyday folks alike?

Still, sun-bathing is not the same as applying cosmetics in one’s bathroom; perhaps the former is more dangerous, but it’s also more fun. Relaxing on a boat deck or stretching out besides a pool implies free time, always a mood-booster. Cosmetics are efficient and effective. One is poetry, the other, prose. Perhaps in life (and when it comes to our skin), there is room for both.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.