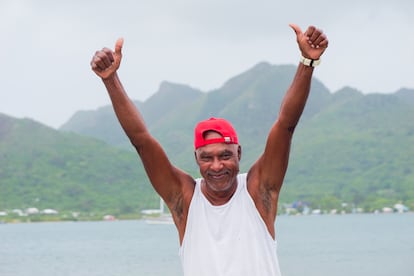

Meet Fly, the guardian of the hawksbill sea turtles on Santa Catalina Island

For 35 years, fisherman Eusebio Webster has been fighting to protect these critically endangered turtles from commercial trade on Colombia’s Caribbean islands

Amidst an endless expanse of blue and green, 10-year-old Eusebio Webster swam in the sea off the islands of Providencia and Santa Catalina, in the Colombian Caribbean. He was accompanied by 50 or 60 hawksbill sea turtles; he encountered them while searching the depths of the reef for fish and lobsters to eat.

At that age, he learned to dive by watching fishermen get off their boats and return home with snapper fish and snails. Then, he started diving himself. He would leave school at 4:30 in the afternoon and go sailing with his friends not far from the bay, returning to land with about 30 lobsters.

Today, at the age of 72, things are no longer as they were. When he goes out to sea and his body floats in the water, he doesn’t spot anywhere near the same number of hawksbill sea turtles that accompanied him during his adolescence. Over the course of a couple of months, he’ll barely see one or two, but he still remembers how incredible it was when they all swam together.

That’s why, 35 years ago, he decided to create a turtle nursery. He did so in a wooden shed, built in front of his house on the shores of the bay. Eusebio explains that the idea is to protect the turtles from a young age, so that they can grow and return to the sea. He wants the youth of Santa Catalina Island to see them when they go swimming in the ocean of their ancestral Raizal territory. The Raizal people are an Afro-Caribbean ethnic group from the Archipelago of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina, off Colombia’s Caribbean coast.

“I take care of them, rescue them, keep them here and feed them until they’re eight months or a year old. After this [amount of] time passes, we return them [to the sea]... and the danger from humans begins,” he acknowledges.

Eusebio or “Fly,” as he’s known in the archipelago, says that, after returning them to the sea, he hopes the turtles will survive. They’re in a so-called “red zone,” due to local consumption and the jewelry trade. “Here, on the island, we have three types of sea turtles: the loggerhead, the green and the hawksbill, [the latter of] which is endangered – its consumption and sale are prohibited. People seek them out a lot, though, because their shells are very thick. They use them to make earrings, bracelets and glasses. The shells of other turtles don’t work for them.”

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists the hawksbill sea turtle as a critically endangered species. This is due, among other factors, to the illegal trade in its shells.

Fly explains that demand for the turtles’ shells in Santa Catalina has been increasing due to tourism. “In my grandfather’s time, when 60 to 100 people lived on the islands, a turtle was caught every month, or every two months. Now, there are 500 to 800 people; there are a lot of tourists and many [other] people living on the islands. And people don’t recognize that the turtles are dying out; they catch them very young.”

In the archipelago, hawksbill sea turtles nest on Manzanillo Beach in Old Providence, where they lay their eggs – which take 45 days to hatch – before returning to the sea. However, there are several threats during this nesting stage: the eggs are often dug up and eaten by dogs, or stepped on by tourists.

For this reason, during the months of July, the Corporation for the Sustainable Development of the Archipelago of San Andrés, Old Providence and Santa Catalina Islands (CORALINA) recommends turning off artificial lights near the beaches, not touching the eggs (much less the turtles), not erasing their footprints, keeping the beaches clean, as well as restricting access to them.

Fly explains that, oftentimes, out of every 150 turtles that are born, only one or two survive. And that’s why his community work is so important: the nursery, in addition to being a place of growth, becomes a refuge during the turtles’ first year of life.

At the hatchery, eight hawksbill sea turtles swim back and forth. They’re distributed among two pools, which are powered by a pump that cleans and changes the water, to ensure that they have oxygen 24 hours a day. There, Fly feeds them snails, shrimp, or shredded fish fillets. “Five or six days before the turtles hatch, we keep an eye on them… and when we see them moving to the sea, we collect them,” he explains.

Fly carries out this work while incorporating an educational element. During the hawksbill sea turtles’ stay in the pools, schoolchildren from across the islands of Providencia and Santa Catalina come to visit them. The conservationist, carrying a waterproof notebook with pictures of the turtles, shares knowledge with the children and tourists, talking about the species, its endangered status, as well as the importance of caring for every turtle they see on the island. Likewise, when the turtles are between eight months and one-year-old, the students accompany him as he returns them to the sea.

“When we release them, we go find the schoolchildren and invite them to return them [to the sea], fostering that love for turtles. This is so that, when they grow up, they won’t trap them,” he explains.

On Manzanillo Beach, Fly says that if those same turtles grow up and survive the 35 years required to reproduce, no matter where in the world they are, they’ll return to the very same beach where they were born to lay their eggs. That’s nature. He also points out that turtles are centuries-old animals, but reaching this age depends on the care and protection they receive.

“We live on this island, we’re from this island. And we have to rescue nature, the sea, the turtles, the manta rays… we can protect them all. It’s really good if everyone does that.”

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.