Submarine cables: The weakest link in Europe’s strategic infrastructure

A succession of major incidents has raised alarm bells and called into question the security of pipelines that are increasingly important for the continent’s communications and energy

Together with the extremely complex cyber universe, they are the great Achilles heel of European critical infrastructures. Underwater interconnections, whether energy (gas and electricity) or data, have been revealed in the last three years — since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine — as one of the weakest flanks of the community ecosystem. Five major incidents, all subject to ongoing investigations, have set off alarm bells and called into question the security of this tangle of hundreds of pipes, the importance of which has grown exponentially in recent decades. Until 24 February 2022, when the war in Ukraine began, the continent’s seabed was believed to be impregnable.

The recent succession of unprecedented outages has added an additional layer of turmoil to the European Union. Although still unproven, the suspicion of sabotage is strong and has forced action. NATO announced in mid-January the deployment of frigates, maritime patrol aircraft, and naval drones to help protect critical infrastructure in the Baltic, the sea that concentrates the bulk of the most serious incidents. Brussels has called in recent weeks for “rapid and decisive measures” to protect these critical infrastructures. And the International Telecommunication Union (ITU, dependent on the UN) created a specific body in December of last year to “guarantee greater resilience of these cables.” Facts and statements confirm the evidence: far from disappearing, concern is growing.

In the case of data cables alone, the UN agency estimates that the annual average of incidents — accidental or intentional — on submarine connections worldwide is between 150 and 200. In 2023, the last year for which there are records, there were 200, at the high end of the range. That’s almost four per week; one day on, one day off. There is, however, no specific data for Europe, the continent that is suffering most from this wave of outages.

“There have always been incidents due to fishing, anchoring failures, or natural phenomena. But rarely have there been so many [in Europe] in such a short period of time,” says Camino Kavanagh, a researcher at the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, with several published studies on critical submarine infrastructure, over the phone. “The important thing is to determine whether it was deliberate. And that is something that cannot yet be stated with certainty.” Sidharth Kaushal, from the British defence and security think tank Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), goes one step further: he believes that the “frequency” of these events in the Baltic “suggests [some kind of] human intervention.”

“The big fear is of a coordinated attack. As citizens, we often don’t notice when a power outage occurs, because there are alternatives: redundancy — multiple routes and alternative connections — allows data traffic to be automatically rerouted along other routes if a cable fails, ensuring that communication continues without significant interruptions,” Kavanagh adds. “Having more cables or alternative systems, such as satellites or microwaves, is essential. But you can’t guarantee 100% supply,” he warns.

In the past three years, more than a dozen of the 40 or so cables that run along the Baltic seabed have stopped working. The first case, in September 2022, was that of the Nord Stream pipeline that transported natural gas from Russia to Western Europe. It was destroyed by underwater explosions that caused the largest methane leak ever recorded on the planet. Although suspicions were initially directed at Russia, the German prosecutor’s office issued an arrest warrant last June against a Ukrainian citizen who had been living in Poland until he disappeared.

The war in Ukraine has had deep repercussions in the Baltic. When NATO was founded in 1949, Denmark was the only country on the Baltic Sea to join the alliance. Today, after the recent accessions of Finland (2023) and Sweden (2024), all of the nine Baltic states except Russia are members of the transatlantic organization. Despite being sidelined, the ports of Kaliningrad — a Russian exclave located between Poland and Lithuania — St. Petersburg, and Ust-Luga are vital for the Kremlin. Thousands of shadow ships sail from them, illegally exporting Russian crude oil.

In October 2023, over a year after the Nord Stream explosions, the Hong Kong-flagged vessel NewNew Polar Bear destroyed the Balticconnector (a gas pipeline between Finland and Estonia) and three telecommunications cables with its anchor.

In the past four months, three other ships have damaged infrastructure in the Baltic Sea — a sea of brackish water and very shallow, averaging 54 meters in depth — with their anchors. Last November, the Chinese-flagged ship Yi Peng 3 disabled two telecommunications cables, one between Finland and Germany, and the other between Lithuania and Sweden. German Defence Minister Boris Pistorius said that “no one believes” that these cables were cut “accidentally.”

On Christmas Day last year, the Eagle S, a ship flying the flag of the Cook Islands and illegally transporting crude oil from Russia to Egypt, severed the Estlink2 (an electricity cable between Finland and Estonia) and four telecommunications cables. Finnish police and border guards boarded the tanker. On Sunday, March 1, Finnish authorities allowed the Eagle S to leave Finnish territorial waters. However, the criminal investigation is ongoing and eight of the 24 crew members are suspected of causing the severing of the five submarine cables with one of the ship’s anchors. Of the eight suspects, three remain in Finland under a court order preventing them from leaving the country.

Both the Yi Peng 3 and the Eagle S had links to Russia, beyond simply setting sail from a Russian port when the damage occurred. Swedish Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson told the Munich Security Conference in February: “We don’t think that random incidents suddenly happen that often.”

Finally, Swedish authorities intercepted the Vezhen, a Maltese-flagged vessel suspected of damaging a telecommunications cable between the strategically important Swedish island of Gotland — the largest in the Baltic — and Latvia, in late January. The ship was released shortly afterwards, as investigators deemed the breakage to have been accidental.

Last week, Swedish authorities launched a preliminary investigation into possible sabotage of Gotland’s water supply network. “Technicians went to the scene and found that someone had opened the electrical system, torn out a cable and interrupted the power supply to the water pump,” a police spokesman told public broadcaster SVT.

Although the beds of the great European bodies of water – from the Baltic to the Mediterranean, from the Black Sea to the North Sea – are full of these interconnections, largely due to the greater population density, they are by no means exceptional. The same is true in America and Asia, as in Oceania. And, increasingly, in Africa as well. The big difference is that for three years now, the European continent has been the scene of the biggest armed conflict since World War II. With ramifications in all areas.

“Given the essential role that submarine [data] cables play in connecting the world, an interruption in the middle of the ocean can be felt in very distant countries,” Tomas Lamanauskas, the number two at the ITU, told EL PAÍS. “The interruption in key cable routes can seriously affect traffic between continents; for example, the cable cuts last year in the Red Sea – which the Houthi rebels in Yemen have turned into another theatre of conflict in the Middle East – affected at least 25% of traffic between Europe and Asia.” Although outside its mandate – “the investigation is the responsibility of the national authorities and the owners of the cables,” says Lamanauskas – the UN arm is “aware” of the recent increase in incidents in the Baltic.

From WhatsApp to email

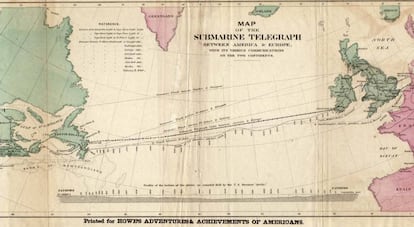

The first submarine data connection was installed in 1851. It was a primitive telegraph cable that ran the 40 kilometres between Calais (France) and Dover (England) through the English Channel. Seven years later, the first transatlantic connection would arrive, between Europe and the United States. This would open a new chapter in the history of telecommunications and also in that of the seas, whose bed would become - over time - fundamental to the possibilities of modern life.

Almost two centuries later, in the data age, 99% of emails, WhatsApp messages, documents, photos and videos that move from one country or continent to another do so through these infrastructures: more than half a thousand submarine cables deployed across the planet with a total length of 1.4 million kilometres. They would be enough to go around the world almost 35 times. Communications infrastructures must also include those for electricity and gas.

Unlike other critical infrastructures, these connections are, in most cases, privately owned. However, safeguarding them is the responsibility of the States, aware that if they fail, basic services for citizens such as the Internet or the supply of electricity and gas are put at risk. A powerful paradox with no clear solution. “Governments have to take on a stronger role in their protection,” Kavanagh claims. “The investment required is high, and there is no clear economic return. That is why public money can be key here. The capacity for repair must also be improved: there is a lack of personnel and the ships [used in these cases] are scarce and, many, already old.”

The King’s College researcher recalls that many public services depend on these cables and pipes – in the case of gas. “However, we have to be aware that it is very difficult to protect the entire European data or energy system. We cannot scare the population, but what has happened in recent months clearly illustrates that we have to be better prepared for this type of contingency.” Is Europe prepared? “To a certain extent, but more is needed. We are not aware of how much we depend on these infrastructures,” Kavanagh replies.

Assuming that without these pipelines the daily lives of millions of citizens would be severely disrupted, the operators of the electricity and gas systems have tried to double the interconnections to avoid the feared total blackout. With relative success: the cost is enormous. So have traditional telecommunications firms, once in public hands, which in recent years have faced competition from technological giants eager to guarantee their own connections.

“In the case of data, satellites are an alternative, but only up to a certain point: their latency [the time it takes for data to travel from the point of origin to the destination] is higher and their transmission capacity is lower. They are a complement, but they are not interchangeable,” Kavanagh concludes. “And in electricity and gas, except in cases where another satellite is running in parallel, there are simply no alternatives.”

The latter supply, gas, is what worries Kaushal, from the British think tank RUSI, the most: “It is the most vulnerable area: the north-east of the EU is relatively poorly integrated with the rest of the [European] network and any cut-off has considerable repercussions for its energy security,” he says. Something, he adds, extends not only to the Baltic but also to the North Sea.

Sources

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition