Far from home: The tragedies faced by migrant children who cross Mexico

Thousands of families in Latin America are forced to leave their homes due to poverty, violence and the effects of climate change, heading towards the United States. Of the more than 828,000 migrants who have crossed the country irregularly so far this year, 97,000 are kids and adolescents

Dafne wants to be a chef, while Roberto wants to be a soccer player. Emiliano likes cookies and cakes. Desireé misses her bunny, Copito. And Marco hopes that his new school will have lots of parks where he can play.

The dreams of migrant children who cross through Mexico don’t fit into a suitcase, even though that’s often the only thing they carry on their way to the United States.

Mexico is the last stop in a long obstacle course that begins in Central America, Venezuela, or even further away. Crossing the country exposes families to violence, kidnappings and extortion from both organized crime and the authorities. It’s a traumatic journey that can take months, or even years, afflicting survivors with physical and psychological consequences that aren’t spoken about very much, but which leave deep marks.

Millions of children and adolescents in Latin America are forced to leave their homes every year due to poverty, violence and the effects of climate change, which have caused humanitarian crises on a regional scale. Five years ago, the majority of people migrating north were young men looking for work. But now, the movement of people has changed: more and more families are leaving their countries in search of better opportunities. Of the more than 828,000 migrants who have crossed Mexico irregularly so far this year — more than double the number from 2023 — some 97,000 are children and adolescents, according to official data. Many of them migrate alone.

Desireé was very young when she left Venezuela. In her short seven years of life, she crossed seven countries on foot, before finally reaching Mexico. She and her mother lived for a while in Peru, but then, the family decided to request asylum in the United States. To get to the north, they had to cross the dangerous Darién jungle, between Colombia and Panama. Then, they passed through Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras and Guatemala.

Upon arriving in Mexico, near the city of Tapachula, her mother tells EL PAÍS that they were almost kidnapped by organized crime. With hardly any money or contacts, they joined a caravan of people and crossed part of the country on the back of La Bestia, a notorious freight train. Many migrants have been injured or killed trying to get on while it was moving. “The train goes very fast. It has wheels and it’s very big,” Desireé explains. “My mom paid a man so we could get on and, when it started [moving], it was nighttime and it was very cold. I almost fell, because you can’t hold on. The bad thing is that it goes very far and then it leaves you behind.”

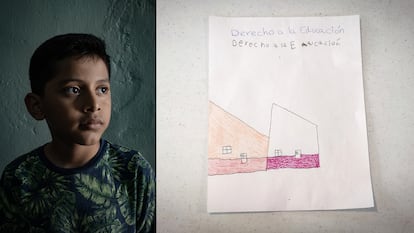

The names of the children in this report have been changed for safety reasons. Still, their guardians have given this newspaper permission to interview them. Many had to leave their homes because of the violence. EL PAÍS — with the support of Save the Children — invites them to draw pictures that depict what they hope their life will be like in the United States. They imagine living in a house, eating delicious food, being reunited with their families and having lots of things to play with.

“I would like life to be better there, for things to not be so expensive and for us to have enough money to buy things,” Desireé smiles.

From Chiapas — on the border with Guatemala — to Ciudad Juárez, in front of the border wall with the United States, families travel more than 1,800 miles just to cross Mexico. Getting there has also become a race against time. The threat of Donald Trump — who aspires to be president of the United States again — has accelerated the flow of thousands of people, who are attempting to request asylum before the elections on November 5.

Desireé, 7, Venezuela

The origins and ages of these children are much more varied than decades ago, reaching historic highs. “We’ve seen an increase in children from Venezuela, Ecuador, Colombia, Nicaragua and Haiti. They’re of all ages, from newborns to teenagers. There’s also been an increase in children coming from Honduras and El Salvador,” explains Ivonne Piedras, director of Communication and Campaigns at Save the Children Mexico.

Children are increasingly migrating at younger and younger ages. According to UNICEF, nearly 90% are under 11-years-old. In 2022, at least 92 of them died or disappeared while crossing the region, more than in any other year since 2014, although humanitarian organizations estimate that the number could be higher. Added to the dangers of the journey are health risks: gastrointestinal diseases, dehydration, malnutrition, foot wounds, dengue and respiratory illnesses. As the route progresses, the situation is complicated by the lack of access to medical care.

Marco is 10-years-old and has lived his entire life in a town in Chiapas, which was a relatively peaceful Mexican state until the war between cartels for control of territory broke out. As a result, thousands of people — including Marco and his family — had to flee. Between 2008 and 2023, some 392,000 people left their homes as a result of violence in Mexico, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center (IDMC). The country has become a source, receiver and transit point for migrants. A third of the people who request asylum in the United States are of Mexican origin.

“I don’t know why we left. Only my mother and grandmother know. One day, they told me that we were going to visit the United States to see my father and I was very happy,” Marco recalls. The family has been waiting eight months for an appointment through the CBP One application — developed by U.S. Customs and Border Protection — to apply for humanitarian visas. “When I see my dad, I would like to talk to him and play basketball,” Marco says. The number of internally displaced people trying to reach the US — including children and adolescents — has been increasing exponentially every year since 2020.

Marco, 10, Mexico

Dafne, her sister Andrea and her uncles are also fleeing violence. They left the Mexican state of Guerrero 10 months ago, after being threatened by drug traffickers. “I’m afraid that they’ll send us back,” the 12-year-old sighs. “We had a fruit shop and they asked us to pay a fee, or else they would kill or rape us. That’s why we came here,” she explains.

Organized gangs and drug cartels also extort and kidnap migrants when they cross the country. Many boys and girls say they’ve been kidnapped and put in “cages” with their parents until they pay money. In addition to extortion and kidnapping, organizations also traffic children for labor or sexual exploitation and use them as mules for drug smuggling. “What has surprised me most about the trip is the cruelty of human beings,” Dafne says emphatically. What she has seen and experienced at the young age of 12 has forced her to grow up too quickly.

Her goal now is to reach Florida, where her parents live. On the day of her interview with this newspaper, she and her relatives are about to go to their appointment with the immigration authorities in El Paso, Texas. After many months, the process of reuniting with her family on the other side of the border has finally begun. “I think that, out of so many things that have happened to me and all that I’ve lived through, now it’s time for me to experience good things. I feel that, after suffering, there has to be a reward,” she smiles.

Dafne, 12, Mexico

“For me, the hardest thing was leaving my friends behind and living with so many people.” Roberto is eight-years-old and arrived in Mexico from El Salvador a few months ago. He now lives in a shelter. While he has already made new friends, he says that he misses his “lifelong” friends.

Not everything is bad in his new shelter. He enjoys playing with the other kids. And he really likes the potato balls with cheese that they serve for dinner, along with the tacos. “Here, they have more meat than in El Salvador,” he points out.

Beyond tacos and potato cheese balls, what Roberto likes most is soccer and Lionel Messi. “When I grow up, I want to go to Miami and play on Messi’s team, or for Manchester City,” he affirms. It’s not surprising that, during the workshop he just had, he drew the Argentine player.

Sadness is one of the most common emotions among migrant children: sadness for being far from home, sadness for leaving the family, sadness for being away from everything they’ve known until now. “We see many children with psychological, emotional and cognitive damage,” Piedras says, from Save the Children Mexico. The spectrum is very broad and each person endures the trip in a different way. The organizations try to work with children on emotional support, education and understanding their rights. This is done through the Humanitarian Aid Consortium, which is funded by the European Union (EU). The group of organizations is made up of the Danish Refugee Council, Plan International, HIAS Mexico, Save the Children and Doctors of the World. Together, they provide care to migrant girls, boys, female survivors of gender violence, as well as LGBTQ+ populations.

On the wall of the shelter, you can see hundreds of messages and drawings that the children have been working on for months. “I lost a friend, but I gained beautiful memories and a pair of glasses,” reads a message that accompanies one drawing. “I lost [when I left] my country, but I won by reaching a better country,” reads another.

“We see hyperactive, very aggressive and angry boys and girls… or, on the contrary, very shy children who don’t want to talk, who have nightmares, who urinate at night, or who have pain unrelated to a health condition,” Piedras explains. Domestic violence is another trauma they experience. “We work with parents to channel emotional relief, because we observe a lot of aggression and [we see how they scold] their children. We also deal with cases of sexual abuse that have occurred on the road. On other occasions, it’s the children who witnessed the abuse of their mothers, or families have been threatened with the rape of their children if they don’t agree to the extortion,” the specialist from Save the Children says.

Roberto, 8, El Salvador

Another serious problem that children face is the educational gap, due to the long journey. Many of them, however, dream of having a school to go to, or studying to have a career when they grow up.

Emiliano is 13-years-old and makes it clear that the first thing he’ll do when he crosses into the United States will be to try the famous Crumbl Cookies, which have more than six million followers on Instagram. “I want to be a baker who makes cakes with edible drawings,” he tells EL PAÍS enthusiastically. “I would like to go to school, have a room with LED lights and a big TV.” When asked what’s the most important object he carries with him, he doesn’t hesitate: his cellphone. On it, he does what any boy his age does: he plays video games, draws and watches videos… although he cannot have social media “for safety reasons.”

Emiliano and his family are also fleeing. “I’ve been told that, in the United States, you can play safely — that you can make many friends and that there’s no violence,” he says.

Humanitarian organizations urge that immigration mechanisms be strengthened and routes be made more secure, so as to protect migrant children and their families. “As long as governments prevent these policies and only try to contain migration, children will be forced to migrate through increasingly unsafe routes. As a result, we’ll see more children being subjected to violence and made to suffer from abuse,” Piedras warns.

Emiliano, 13, Mexico

At the end of the road, the dreams of migrant children collide with reality. They cross jungles, rivers and deserts, but the horizon is always a little further away. The idea of a life on the other side, however, pushes them to continue forward, despite everything they carry on their shoulders. “My dream is to save up money with my mother and buy a house. We’ll live there while we save more money,” Roberto notes.

“What I saw of the United States looked very nice,” Desireé adds. “The houses and hotels looked very tall. But on this side [of the border], there was a red gate with cables and many immigration vans to detain people,” she remembers. She also dreams of having her own house and, one day, of being “a painter, a doctor, a basketball player and making pizzas” — her favorite food.

She still doesn’t know what her path will be. Maybe, when she’s older, she’ll be able to decide.

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani.