The lives destroyed by the Israeli offensive in Gaza

After three and a half months of attacks on the Strip, more than 25,000 Palestinians — at least 70% of them women and children — have been killed. Four people tell EL PAÍS about their desolation and describe the daily life of a devastated territory

Kayed Hammad has moved houses with his family 14 times since the start of the Gaza war. The elderly Redwan couple was killed with one of their children and a caregiver in a house in an affluent part of Gaza City that they never imagined would be bombed. Abed Mustafa fights a daily battle in Rafah to obtain food and water for his family, and to charge his cell phone. S. A. (who prefers to remain anonymous) shares an apartment with 13 other people after fleeing with her mother. They managed to stay alive, but their house and all their memories were destroyed by Israeli strikes.

These four Palestinians have shared their desolation and described their daily lives in a series of conversations with EL PAÍS. They have been living in a devastated occupied territory for three-and-a-half months of bombardment, in which more than 25,000 Palestinians have been killed, the overwhelming majority of them women, children and the elderly.

The curse of moving houses 14 times in barely 100 days

Jabalia refugee camp

In a curse that doesn’t end, Kayed Hammad has been forced to move homes 14 times with his family since the start of the Gaza war. Today, with barely any winter clothes, he wanders in search of some food among the ruins of the Jabalia refugee camp, in the north of the Gaza Strip. He was born there 60 years ago, after his family escaped the Israeli bombings that devastated his home in Gaza City, the de-facto capital of the coastal enclave. “Last Christmas Eve was the worst night of my life, because I suffered a heart attack,” he recalls, in an arduous exchange of messages. “When I arrived at the hospital, they could only offer me anesthesia to relieve the pain… I should have a check-up with a cardiologist, but there are none available.”

Smiling and vital in August 2022 — the last time he spoke with EL PAÍS before the Israeli invasion of the Strip — the images that this Gazan sends along are those of a defeated man. He has long worked as an interpreter for NGOs and foreign journalists. “I don’t see anything good in the future,” he notes. “They say that we’ll need 10 years to rebuild Gaza.” He’s saddened by the landscape of devastation in northern Gaza, which his photographs convey. The vast majority of the 1.1 million inhabitants who were living in this part of the Strip have had to flee to other areas. “Those who went south are suffering in the open-air, [living in] plastic and cardboard tents. Many are repenting and now they tell us: ‘I wish we had died instead of leaving,’” he laments. “They (the Israeli authorities) told them it was a safe place, but almost every day, they’re bombed in Rafah or Khan Yunis.”

Hammad would like to be in Spain with his brother — with whom he lived three decades ago — and return to practicing the Spanish he learned back then with his friends. “Any human being deserves to live in peace, to have a normal life,” he insists, with a feeling of regret for the fate of the rest of the 2.3 million Gazans.

Like most of the inhabitants of the Strip, on the night of October 7 — during the attack by Hamas on Israeli targets — he was sleeping when the explosions woke him up. “From the window, I saw many rocket attacks and detonations from the [Iron Dome, the American-provided Israeli defensive system]. When the invasion occurred, we didn’t notice much difference. Until the shots from the tanks got closer,” he recalls.

“What are our days like here? Many nights, we didn’t manage to sleep even two or three hours, especially when the [Israeli military] operation was concentrated in the North. With so many bombs, you sleep at most for an hour, when you’re already so exhausted that you cannot resist,” he describes. “But then, you wake up to an explosion.”

In the mornings, he has to take a risk and go out to get anything to eat for his family. Before the war, 500 or 600 trucks with goods entered Gaza on a daily basis. “Being able to get to where something is sold now — if someone still has a store in a hidden alley — requires taking a very big risk,” he acknowledges.

“Drinking water… we’ve already forgotten what [that was like] a long time ago,” he says.

“You always have to return home as soon as possible and wait for the next day. And it’s the same. More of the same. You feel helpless. Many things leave a bitter taste. You would like to feed your children and you can’t,” Hammad says over the phone, with sadness in his voice.

During the first week of the offensive, his house was destroyed by Israeli bombings. This wasn’t the first time. In 2003 (during the Second Intifada) and in 2008 (Operation Cast Lead) he previously lost his home to the Israelis. “I don’t know when I’ll have a house again. I hope I can at least have a normal grave. Now, they bury [the bodies] in public squares, anywhere, because you can’t get to the cemetery.” He says goodbye, not hopeful for Gaza’s future.

A witness from the West Bank describes the disappearance of her family

Ramallah / Gaza City

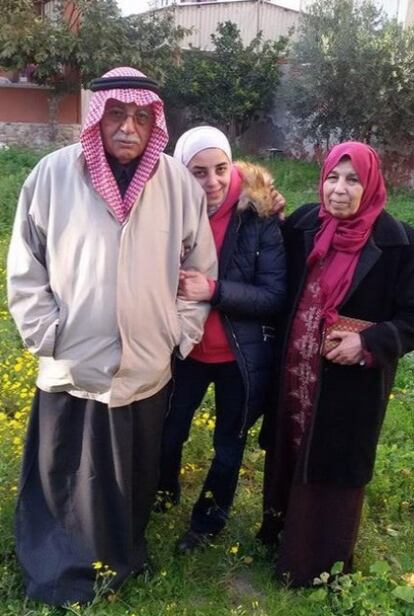

In the first days of the invasion of Gaza, elderly Amer and Nama Redwan didn’t fear for their lives. They were convinced that the Israeli forces would never bomb their two-story house with a garden in Tel al-Hawa, one of the best neighborhoods in Gaza City. “Nothing is going to happen, don’t worry. We’re in a very safe area, next to the Red Crescent, international organizations... They’ve never bombed here in the past,” Amer reassured his daughter, Iman, on the phone. From the West Bank city of Ramallah — where she moved from Gaza upon getting married — she was overwhelmed with emotion for her parents, fearful about the news of Israeli airstrikes killing hundreds of Palestinians on a daily basis.

On October 9, the wife of Ramadan Abu Aljar’s — a friend and caretaker, who insisted on accompanying the Redwans in their most difficult times — tearfully telephoned Imam to tell her that her son hadn’t seen anything standing where the home had been. An aerial bombardment had destroyed it hours earlier. Inside were 83-year-old Amer and 77-year-old Nama, one of their children — 38-year-old Hussein — and Ramadan, 52.

A neighbor told Iman that, half-an-hour earlier, he had urged Amer and his family to escape. The Israeli forces didn’t warn about the imminent bombings, but people fled when they heard the noise getting closer and closer. “I said to him: ‘Come, haj’ (an expression of respect used for those who have made the pilgrimage to Mecca, or simply for an elderly person) and he replied: ‘Why? The Israelis know who lives in each house and that my wife is in a wheelchair with an oxygen tank. This isn’t a big block and there’s no one from Hamas or [Islamic] Jihad.’”

The bodies of mother, son and Ramadan were soon pulled from the rubble, lifeless. The rest of the children hurriedly hired a private excavator by phone to look for their father. Three days later, the operator called Iman when he smelled decomposition near the place from which her mother was extracted, but she clung to the fact that it was the corpse of the cat, Loco. “No, I’m sorry, I’m just looking at the cat on the pile of rubble,” he told her.

“If you think about the overall situation, you feel like what happened to you is just a drop in the ocean. And there are things I choose not to think about, because I would go mad. Like my niece, she’s lost her father. Or I wonder if the stray dogs are eating my father, mother or brother.” She says this because they’re buried in the Al Fallujah cemetery, in the now-devastated Jabalia refugee camp. Israeli troops have caused damage to graves in that and five other cemeteries in Gaza, oftentimes using bulldozers to dig up graves, as verified by images taken on the ground and by satellite. Al Fallujah is the only cemetery in which — amidst the most intense bombing in decades — an acquaintance found two places for the three bodies.

Like 80% of Gazans, Iman’s parents were made refugees by the Nakba (“catastrophe,” in Arabic) in 1948, which resulted in the expulsion of 800,000 Palestinians and the massacre of tens of thousands of them by settlers. When Israel conquered Gaza from Egyptian troops in the 1967 Six-Day War, the family fled again, ending up in Saudi Arabia. Nama — Iman’s mother — was an Arabic teacher. Amer, her father, was an administrator-turned-businessman. They had seven children and returned to Gaza in 1988, where Iman attended high school and studied Journalism at the Islamic University, which has now been destroyed by the Israeli offensive.

Iman still uses the present tense when talking about her parents: “My father is… my mother likes…” She last saw them in August. The Israeli siege prevented them from leaving the Strip (like almost all Gazans), so the only option to meet their 52-year-old daughter and see their grandchildren was for her to enter, which required permission from the military authorities. Given the difficulty of achieving this, Iman spent three days and a large sum of money crossing several countries to reach Gaza. Even though Ramallah and Gaza City are less than 50 miles apart by land, she was forced to go by road from Ramallah to Jordan, spend hours waiting at the crossing, take a flight in the opposite direction from Amman to Egypt, before finally arriving by road through the Rafah border crossing with Gaza.

The odyssey of charging a cell phone to keep in touch

Rafah

Speaking with Abed Mustafa depends on the sun. There’s been some luck on the day of his interview: it’s sunny in Rafah, in the south of the Gaza Strip. Like he does every morning since the Israelis began bombing, Mustafa walks about four miles to charge his phone at his friends’ house. They have solar panels (the Israeli government has cut off all electricity to the Strip) and do him the enormous favor of letting him use an outlet for free. But on rainy days, he has to pay people who own small generators to recharge his battery just a little. He wouldn’t have been able to respond to EL PAÍS during such weather conditions.

“Each act of daily life — the simplest thing — requires enormous effort. I’m tired,” this 24-year-old Palestinian sighs. He prefers that his real name not appear in this interview. “But having a battery on my phone is the most important thing for me. I can call, hear from loved ones and find out what’s happening…”

Before October 7, Mustafa lived in a small apartment in eastern Rafah. He had renovated it himself. It was a kind of refuge, in which he boasted of his independence and received his friends. On October 9, he was forced to flee his home. Now, thanks to the bombs, it has become a mountain of rubble.

“I stayed at U.N. schools, at relatives’ houses… Now I’m at my grandparents’ house in Rafah. There are 27 of us living in three small rooms,” he explains. With him are his parents and his six brothers and sisters, all younger than him. The youngest, Mohammad, is only two-years-old. “Every day is similar: I charge the phone, I return home and the next battle begins: how to eat and find water. Everything is very hard. For example, looking for water means walking for miles until you find someone who sells or distributes it. I pray a lot before leaving home. I ask God to help me find what we need.”

Necessity has made Mustafa and his father devise new ways to survive with dignity. They have built a home oven — where they can bake the bread they make themselves — and a precarious heater made of metal and plastic, so that the children can wash themselves with hot seawater “when possible.”

The connection comes and goes. Mustafa has coverage thanks to his neighbors, who connect to an Egyptian network. The questions and answers lag — he has to repeat himself several times. Time is of the essence, because the battery runs out fast. “The other day, I went out to look for oil at a market. A bomb fell in the area half-an-hour after I left. 30 people died. Maybe they were looking for oil like me,” he recalls.

Mustafa has a degree in English Language and Literature from Al Azhar University in Gaza, another university destroyed by the Israeli onslaught. He has worked as a consultant, trainer and program coordinator for international and Palestinian organizations. However, he was laid off in March 2023. He has never been able to leave the Gaza Strip. “I didn’t have any luck, I applied for scholarships to do a master’s degree, but they didn’t select me. I didn’t care where I would go — we Palestinians go wherever the opportunity arises,” he says.

The life of this young man represents that of tens of thousands of inhabitants of the Strip, where 60% of the population is under 25-years-old. Many have earned degrees and speak English fluently, despite never having been allowed to leave the small territory of 140 square miles. However, even though Gaza has one of the highest literacy rates in the world, due to the 17-year-long Israeli blockade, many Palestinians who live in the Strip are unemployed. According to official figures, 70% of Gaza’s youth didn’t have jobs before October 2023.

Now more than ever, Mustafa feels trapped. “I hate this, I hate it. There are people everywhere, the house is full, the streets are full. You can’t even walk. Every day, there are more displaced people, more tents…”

His exhaustion is mixed with immense sadness, as he remembers the family and friends he has lost since October 7. “The death that has hurt me the most was that of my uncle. He hated Hamas and everything it represents, but Israel killed him in his house with eight other people,” he recalls. “The other day, they bombed the house of a friend from university, here in Rafah. The entire family died, except him. He was badly injured. He’s now [like] the living dead,” Mustafa adds quietly.

Mustafa’s family’s money ran out days ago — banks are closed (or destroyed) and prices have skyrocketed. They survive thanks to the humanitarian aid that comes in through Rafah in trickles, where trucks are being held up by Israeli forces. They eat preserves and whatever they find and prioritize feeding the children. “I don’t know how long it’s been since I last ate meat. Whenever I find it, it’s too expensive. My hair is starting to fall out, I think it’s from eating so badly,” he explains.

But that afternoon, there was some luck: the family had falafel for lunch, thanks to a friend of Mustafa’s. “Everyone is skinny. People are starving and chasing humanitarian aid trucks. Tonight, I feel calm, because I know that tomorrow, we have something to eat,” he says.

“What’s next? I don’t know. People are worried about just living through the day. My family and I are totally apolitical, but it will be difficult for Israel to put an end to Hamas, which is an undeniable reality in Gaza, with a strong structure and not just a military one,” he thinks out loud.

His cell phone battery is running out. Mustafa has to hang up. “Do you know what scares me?” he says, before saying goodbye. “That we’ll get used to this: to the bombs, the lack of food, the schools converted into shelters, the death…”

Teaching children how to cope with pain

Rafah

This interview is postponed several times, due to bombing in the area. To get a connection and to be able to answer this call, the psychologist must travel to a place where UNRWA — the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees — operates.

Based in Rafah, in the south of the Gaza Strip, S.A. doesn’t want her name to be published. “I prefer to be anonymous for my safety. And, furthermore, my story is that of many others… it doesn’t need a name,” she explains.

She’s 39-years-old and works for Doctors of the World. She fled her home in Gaza City and first took refuge in the center, in Nuseirat. Finally, she rented a small apartment in Rafah, where 14 people now live. “My worst moment was running away from home to save my life, driving like crazy to get out of that area. At the same time, I was looking at the face of my elderly mother, who was coming with me. I lost my home and all my memories. It hurts a lot,” she explains.

Being displaced twice hasn’t stopped her from continuing to practice, especially with children. In schools converted into shelters or improvised camps, S.A. and dozens of other psychologists are already beginning to delve into the invisible wounds of more than 100 days of bombs, loss and fear. “I chose to be a psychologist to help people; it’s in my soul. I want to help those children,” she explains.

The help they provide is a kind of “psychological first aid” — an emergency therapy. “We help them cope with the pain; we begin to provide them with emotional support to identify [feelings], express difficult emotions and [learn] practical tricks to cope with stress and fear, such as breathing exercises,” she explains.

The children suffer from serious mental disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, or depression. Games and arts and crafts help the children begin to express their emotions in front of psychologists and feel accompanied by their peers. “We play, we paint with them, we talk to their families, if they have families left... We can’t do much. We can’t hope now to launch more ambitious programs to protect their mental health, but at least we try to make them feel a little bit of relief and security,” this psychologist notes.

According to the UNRWA, more than one in four patients examined at its centers in Gaza before this military offensive broke out needed psychosocial and mental health support. In the case of Palestinian children, most were already traumatized well before October 7. A report published by Save The Children in 2022 concluded that since the Israeli government imposed a land, air and sea blockade in 2007, the lives of Gaza’s children have been mired in severe deprivation, cycles of violence and restrictions on their freedom. Their mental health was already at a critical point. Around 80% of children reported feeling like they were in a permanent state of fear, worry, sadness and pain.

“I remember, for example, a seven-year-old boy who had lost his parents and four brothers in an airstrike. Only he and his sister — who’s about 15-years-old — were saved. He’s now in a shelter with relatives and is in very bad condition. He sleeps poorly and has nightmares. He cries, he shouts and he doesn’t want to talk to anyone.”

S. A. explains that the boy didn’t want to participate in any activity proposed by the psychologists. He was constantly reliving the moment of his parents’ death. “He felt guilty for what happened. When he started to talk, he said that he wanted to die. It was a very difficult case. I spent a lot of time with him, talking to him, inviting him to participate in some activity and, little by little, he began to partake in the games and began to open up. He’s a child who will need many individual sessions and many years to be minimally revived. As a psychologist, I can tell,” she emphasizes.

S. A. clears her throat and takes a few seconds to regain her composure. As a single woman, she uses the same techniques that she teaches children with her mother, her nieces, and even with herself. She breathes deeply, thinks positive thoughts and takes other steps to calm down.

She’s part of a team of around 20 people, four of whom are psychologists. Their managers accompany them to detect if they’re about to faint and help them take a break when they feel emotionally overwhelmed. For example, when a colleague or friend is killed or injured in the bombings, as has occurred often.

“The situation is getting worse every day. It’s very hard. I’m a psychologist, but I’m also a human being and I suffer. I try, from the bottom of my heart, to be strong with the children, with my family and do something for them, even if it’s a little,” she affirms.

Doctors of the World has warned that the extreme violence being inflicted on the Gaza Strip and the atrocities witnessed by children “can cause irreversible damage to their mental and emotional development,” which “won’t disappear when the violence stops,” since a percentage will develop more serious mental disorders that will require specialized care. “But for now,” S.A. clarifies, “we cannot think about the future. We don’t know what else can happen to us. We live day to day.”

These interviews were conducted via phone calls and email. Foreign media outlets are prohibited from entering the Gaza Strip by the Israeli authorities.

Créditos

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition