And after first contact, what? How the last isolated peoples on Earth live

A journey to some of the most remote corners of the Peruvian Amazon provides several lessons for the future

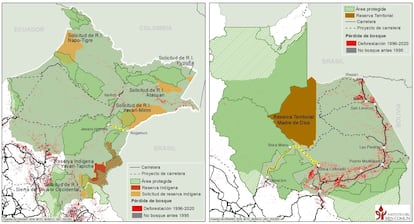

The eastern Amazon is home to vast tracts of jungle with the highest concentration of indigenous groups in voluntary isolation on the planet; peoples who a century ago took refuge in the most inaccessible corners of the jungle after fleeing from slavery in rubber plantations. Since then, they have been self-sufficient, living outside the market economy, consumer goods, and the abstractions of the nation state, traveling between Peru and Brazil along trails now exploited by drug traffickers, in lands surrounded by illegal fishermen and coveted by loggers and miners. Despite all this, their territories remain among the best preserved in the basin and are a priority for climate, biodiversity, and global food security, the three major challenges of a decade that will determine the future of the planet.

For most of society, dependent on money, cell phones, and fossil fuels, the questions are many: how do the last isolated peoples of the Earth live? What is it like to share the land with them? How have the peoples who joined the outside world fared since first contact a few decades ago?

This newspaper has traveled to some of the most remote corners of the Peruvian Amazon to talk to the Matsé Indians who came out of isolation in 1969, and to document the coexistence between a settlement of Yine settlers and the Mashco-Piro. The former are the grandchildren of slaves who killed the rubber boss and fled south; the latter, descendants of other Yine speakers who allegedly chose to move deeper into the forest, becoming the largest isolated population in Peru.

This news outlet has also traveled to the Amazonian city of Pucallpa to meet a new generation of Isconahua, a group forcibly contacted half a century ago and abandoned on the margins of society; without a voice in the decisions that affect them, but determined to change their fate. And threaded into these stories are Spanish researchers, a bishop from León and Gustave Eiffel. Three indigenous peoples, three stories, and many lessons for the future of the Amazon.

The strange return of the Mashco Piro

In the southwestern Peruvian Amazon, a community of Yine settlers is experiencing an unprecedented and, for the moment, unexplained phenomenon. Since the beginning of the year, members of the country’s largest indigenous group in voluntary isolation have been sneaking into their plantations. They slip in stealthily and on tiptoe, with blunt machetes swiped years ago from illegal loggers, and retreat carrying bunches of ripe bananas. Before melting into the forest, they leave crossed branches as symbolic barriers: “Do not follow us.” The first is a warning. The second, a reminder. The third, the last chance to turn around. The residents of Monte Salvado have learned to respect them.

In 2010, a group of locals were looking for the right tree to make a canoe, which is essential for getting around the jungle wetlands. Along the way, three of these no trespassing signs were ignored. They understood what they meant, but did not heed their warnings. On their way back, when they reached the banks of the Piedras River, the teenager at the head of the party collapsed. A bamboo arrow, flying at more than 150 kilometers (93 miles) per hour from a reed bed, had just pierced his abdomen. The tip measured 25 centimeters (9.8 inches). Against all odds, he survived. His life has never been the same again, but he bears no grudge against the isolated people who shot him.

“A jaguar attack is not cruel, and neither was this one,” says Vargas, now a thoughtful 27-year-old who seems to have several lifetimes behind him. “The Mashco Piro are people like you and me, and they have suffered a lot at the hands of illegal loggers ... They fired because they must have thought we meant them harm too.”

A century ago, the Mashco Piro people retreated to the headwaters of the rivers to escape subjugation in rubber camps such as the one that stood around the present-day settlement of Monte Salvado. The rubber boom passed, but in the 2000s, the mahogany and cedar boom arrived. International prices for these luxury woods attracted thousands of illegal loggers to the Madre de Dios reserve, created to protect the isolated people.

A body in the sand

During the timber boom, a then community policeman and former Monte Salvado logger found himself leading a strange mission: to recover the body of an indigenous girl who had been murdered and buried in a shallow grave on a beach on the Piedras River.

“In the mid-2000s, loggers hired 22 mercenaries to kill calatos [derogatory term for “isolated people”] in the Madre de Dios Reserve,” explains a local expert on isolated peoples, who asks that his identity be protected for fear of reprisals. After killing the girl, the henchmen followed her tracks into the forest to liquidate other members of the group, he says. By the time the community policeman’s boat reached the beach, the body had already been washed away by the rising waters of the Amazon river. From that moment on, events moved quickly: members of the isolated group attacked the loggers in the so-called killings of quebrada Perro and quebrada Seca (two jungle streams); the president of the Native Federation of the Madre de Dios River and Tributaries (Fenamad) denounced the loggers’ incursion onto the reserve to the United Nations. The prices of mahogany plummeted on global markets and, in 2008, loggers began to migrate in search of more lucrative activities, such as illegal mining.

That invasion passed, but the renewed trauma of the Mashco Piro changed their relationship with the settlers of Monte Salvado, a village founded in isolated territory shortly before the logging boom. With the incident on the banks of the Piedras River in 2010, Nilo Vargas became the first member of the community to be wounded by arrows (“picado,” as the locals call it). In 2017 and 2019 there were other incidents. Then, the Mashco Piro disappeared from the vicinity of Monte Salvado. Until this January.

Monte Salvado has a plan

Wednesday, June 7, 2023. An expert from the Fenamad indigenous federation consults his cell phone in his office. There is a message. It has been sent by the official control and surveillance post of Monte Salvado, whose objective is to prevent third party access to the Madre de Dios reserve and to manage the peaceful coexistence between isolated groups and the community. Report: “At the time she was collecting firewood behind Romuel P.’s chacra [orchard], Vilma C. sighted a PIA [indigenous person in isolation]. Realizing several other PIAs were present, she immediately ran away.” Earlier in the year, Vilma had already had a chance encounter with a lone Mashco who was taking her yucca. They made eye contact and he, apparently as surprised as she was, melted into the forest.

Monte Salvado is one of the seven surveillance posts that Fenamad created in the southern Amazon and now shares with the Ministry of Culture, which is responsible for this matter. The agents patrol on foot and by boat around the community; keep a daily log of sightings and signs of isolated peoples’ activity in the area; and notify the locals, the indigenous federation, and the authorities. If you come across a Mashco Piro trail, the rule is clear: turn around and wait four days before returning. And if the isolated people have left no trespassing signs, respect them.

“For months now, a group of Mashco have been entering our farms on a weekly basis, sometimes every other day, but we don’t know why this change in their movement patterns has occurred,” explains agent Belizario Sebastián, astonished. “We recognize them from previous years by their footprints: one of them has an injured foot,” he says during a patrol in cassava and papaya orchards.

If you come across a Mashco Piro trail, the rule is clear: turn around and wait four days before returning. And if the isolated people have left ‘no trespassing’ signs, respect them.

The Mashco Piro are the most visible isolated people in the Peruvian Amazon, especially since more than a hundred members gathered in front of the village in 2013 to ask for bananas and ropes in a variant of the Yine language. In other places, the presence of isolated people has been documented, but their ethnicity is unknown and no one has been able to talk to them.

In turn, Monte Salvado is the community with the most isolated people sightings in the Peruvian Amazon. The agents ban illegal fishermen from the reserve, the locals adapt their hunting habits so as not to interfere with the isolated peoples — knowing that they are the ones who settled in the indigenous group’s territory and not the other way around — and even the children know what to do when they hear “Mashco!”: stay calm; head for the safe house next to the guard post; and huddle under the kitchen sinks, along with their beloved baby spider monkeys. “If you don’t have time to leave the house, you cover the windows with blankets or mattresses so that [in a worst-case scenario] arrows won’t get in,” explains Kasumi, a cheerful and quick-witted seven-year-old girl, during a drill. Everything that can be planned for is planned for: an agent to communicate in Yine language with the nomole (brothers), people to document the event with photos and videos, and a person in charge of changing the post’s satellite internet password so that only the agent responsible can communicate verified information.

Cross-border collaboration

The lessons learned from Monte Salvado are already helping other communities on the Brazilian side of the border. Last year, monitoring agents from the Fenamad indigenous federation traveled to southern Brazil, also a Mashco Piro territory, to share their experiences with local communities and the CPI-Acre non-governmental organization[WG1] . “After a few weeks, the Mashco appeared on the other side of the river, but the villagers already knew how to act,” explains Fenamad’s expert on peoples in isolation, Israel Aquise

With the recent change of government in Brazil, one of Aquise’s objectives is to resume binational talks with NGOs and authorities that were put on hold under the administration of Jair Bolsonaro. The idea is to build surveillance posts on both sides of the Acre River and ensure that they work in a coordinated manner, given the cross-border nature of the isolated groups and the threats they face.

The same is happening a few hundred kilometers further north, where the Yaquerana River separates the Peruvian region of Loreto from Brazil’s Vale do Javari. The indigenous organization UNIVAJA and the Regional Organization of Indigenous Peoples of the East (ORPIO) met with government officials in Lima in June to urge both states to coordinate monitoring posts, among other things. “The problems on both sides of the river are identical,” sums up UNIVAJA member Manoel Chorimpa. These include illegal fishing, the advance of drug trafficking, and impunity for the harassment and murder of indigenous people and environmentalists. Neither Peru nor Brazil has yet ratified the Escazú Agreement, a groundbreaking treaty by which Latin American states pledge to protect those who want to protect the environment in the world’s deadliest region for these activists.

The man who talks to isolated people

“All of you who wear this [pointing to clothing] are evil.” This is one of the first phrases Damián heard from the mouth of a Mashco Piro man, one listening from the river lookout in front of a guard post, the other projecting his voice from the opposite bank of the river. Damián, an indigenous Yine man as extraordinary as he is discreet, speaks under a pseudonym because of the sensitive nature of his work on behalf of the isolated peoples together with indigenous bodies, the authorities, and anthropologists.

Every Amazonian summer, when the water levels drop, the isolated people descend from the headwaters to the beaches to collect taricaya turtle eggs, a primary source of fat and protein. One of these groups has established a special relationship with Damián. They call him “river wolf” because of his skill as a fisherman, and he knows their favorite colors: red and black, the natural colors of huito (Genipa americana) and achiote (Bixa orellana) with which they paint their bodies. From a distance, the Mashco explain how they hunt, but are careful not to give details about where or how they live. Then, their naked, muscular bodies vanish back into the tangle of the forest.

The first time Damián communicated with isolated people on the other side of the river, the adrenaline of the moment gave way to the awareness of a shared humanity. In time, Mashco Piro youths would eventually tell him how they had wept around a mighty tree felled by illegal loggers. They used to eat the fruit of that tree.

An evangelical sect was planning to take Mashco Piro youths out of the jungle by tempting them with gifts, he says, contrary to national and international norms that recognize the right of isolated people to non-contact and self-determination. “Once they have tasted salt and sugar, how are you going to continue to provide for them?” Damián asked them, recalling that, elsewhere, survivors of forced contact spent their lives wondering why they had been taken out of the forest only to be abandoned.

After the first contact

The Isconahua were contacted by an evangelical group from the United States. They had small planes, megaphones and guides who spoke languages from the same linguistic family. Some Isconahua died when the canoes that were taking them away from their sacred mountain refuge capsized. Others succumbed to ailments from the outside world for which they had no immunity, such as gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases. Half a century later, those who survived are still trapped in a state of permanent limbo: without a land they can truly call their own, without a voice in political processes, with only a handful of people fluent in the language, but without the means to teach it in public schools.

According to the Peruvian government, the Isconahua remain in the category of indigenous people in initial contact, which suggests that they are not organized or prepared to participate in decision-making that affects them. The state is responsible for the well-being of these peoples, but it has yet to develop policies that facilitate their integration and provide an outlet for territorial demands for their subsistence and cultural continuity.

William Ochavano, Isconahua youth

“The government focuses on isolated people, but what happens when they make contact?” asks Isconahua youth Felix Ochavano. “We were abandoned on the margins of society. Decades have passed, but we continue to feel invisible.” A sentiment shared by groups such as the Chitonahua, who have moved from place to place until they took possession of land borrowed from another indigenous people near the Brazilian border; a place too small to hunt and fish and too temporary to develop other economic activities.

Peoples such as the Isconahua are a source of fascination for researchers from all over the world, who cannot study their isolated relatives because of the no-contact principle enshrined in the national and international legal framework. “They tend to treat us like an academic curiosity that needs to be investigated before it dies out,” says William Ochavano, Felix’s older brother. “There are many who have analyzed us as objects of linguistic or anthropological research, but few who are concerned about our needs in terms of health, education, employment, or political representation.”

The Ochavanos represent a new generation of Isconahua. When they were little, other children taunted them by shouting “hey, Isco!” As adults, they were met with scorn from a string of bureaucrats, and even teachers, who told them to their faces that the Isconahua no longer exist. Years ago they managed to secure a piece of land, Chachibai, with the misfortune that the deed is also in the name of a local clan of Shipibo loggers who are seeking to sell the territory. The case is before the courts.

William and Felix Ochavano, who are trained as a teacher and an engineer respectively, are tired. Tired of papers, insults, and courts; tired of sending letters to the ministry, to the regional government, to the local technocrat, to indigenous organizations here and there. They are exhausted, but the fire accumulated over decades of submission, mockery, and contempt in the lower echelons of society has not got the better of them. The brothers have created the first organization to represent the interests of the Isconahua people to regional and national authorities. They have already laid the foundations for a cultural center and intend to bring together representatives of all the indigenous groups in initial contact in the Ucayali district, where there are some 200 indigenous people. The objective is to jointly address common problems and promote support policies for their communities and for isolated fellow countrymen who, in the future, may face the same problems they face: life after first contact.

Lessons in jungle survival

As they near the end of their lives, the Matsé elders, who had lived in isolation, feel the urge to share memories they had hitherto kept to themselves. Salomon Dunu Uaqui Moconoqui and three other elders are preparing to go into the forest with a new generation that, they say, is losing the skills to survive in the wild. Undoubtedly, something has changed.

In their braided leaf baskets are the few belongings of the semi-nomadic groups — resin pots, fishing poles, palm fiber hammocks, ceramic pots — and other objects of post-contact life, such as FC Barcelona T-shirts and bottles of InkaCola. The groups that continue to live in isolation as a survival strategy live in the same way these elders did until 1969. But for some groups in the neighboring Yavarí-Tapiche Indigenous Reserve that they maintain to this day.

Salomon Dunu Uaqui Moconoqui and company show how they hid among the leaves; how they would flee on tiptoe and in single file; how they would leave a man in the rear to erase the signs that they had been there — bent branches, trampled plants, footprints in the mud — and throw their pursuers off the scent. To communicate without arousing the suspicion of the “mestizos” [non-indigenous] they assigned each person an animal sound. When they sighted an invader or faced danger, they warned each other by imitating the corresponding sound. Suddenly, in the middle of the demonstration, there is a burst of laughter in the forest. “They’re being answered by a real monkey and a real partridge,” the youngsters explain, cracking up. The isolated people with whom they share hunting areas do the same to this day, with such perfection that only the true inhabitants of the jungle can distinguish whether they are humans or animals. Therefore, the testimonies of indigenous people such as the Matsé are an indispensable first step to ringfence and protect the territories of isolated groups; an exercise that now faces a campaign to discredit the indigenous voices that coexist with isolated people by negationist businessmen.

Alternatives to “ground butter”

The creation of the Yavari-Tapiche reserve in 2021 was a victory for isolated people. However, despite all their survival tricks, there are overwhelming threats that lurk: an attempt to open an illegal road between Peru and Brazil that has been simmering since the 1960s, when the government responded to Matsé opposition with aerial bombardments; the threat of oil, which they call “ground butter”; and a dance of illegal fishermen, tourists, and loggers seeking to sow discord in the community with a new hook: money.

Fathers against sons and brothers against brothers. Indigenous people who feel they are a physically and spiritually part of the forest, such as Salomón Dunu, co-author of a 500-page tome on medicinal plants, versus those who deny the documented existence of isolated people because they aspire to work for oil companies, loggers, and builders with political influence. And in the background, the lack of alternatives to generate income to meet the needs of the new generations: fuel for the boat; cartridges for the shotgun; batteries for the flashlight, and money to study and receive medical care in Iquitos, the capital of the huge Amazon region of Loreto.

Aware of this, international actors such as Rainforest Foundation Norway (RFN) are mobilizing funds to protect two transboundary territories with a combined area larger than that of the United Kingdom; globally important forest zones inhabited by isolated peoples migrating between Peru and Brazil. The backbone of this combined human rights, biodiversity, and climate protection strategy is the local communities themselves.

“We consider it a priority to support indigenous peoples bordering the territories of isolated groups so that they can develop alternative sources of income, both for their own well-being and for the protection of these vulnerable groups,” says RFN project coordinator Armando Lamadrid, by phone from Oslo. “The goal is to combat the drivers of deforestation and protect the cultures and ways of life that have kept these forests standing for millennia.”

Mercury and arsenic in the body

This May, the Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal) in Barcelona published a study on the impacts of oil extraction in northern Loreto, the most polluted area of Peru. Conclusion: Indigenous people in four watersheds have elevated body levels of mercury, arsenic, cadmium, and lead, all of which are toxic to humans. The health effects of these metals range from cancer to severe neurological damage, childhood developmental delays, kidney disease, and bone fragility.

The latest company to exploit oil in this area is the Canadian company Frontera Energy. According to its website, it is committed to running its business “safely and in a socially, environmentally, and ethically responsible manner.”

Antonina Duni does not need to know what an epidemiological study is or to read corporate commitments. As an indigenous Matsé, she is well aware of the impact of half a century of oil spills on other native communities. “You are the ones who buy the food,” says Antonina Duni, wife of an former isolated person, as she returns from hunting armadillos with her dog Sasha. “We get all our sustenance from this river, from these forests, from this soil.”

Her neighbor Sara Beso Dunu Duni Beso is there too, as she weaves palm fronds to renovate the roof of her house, which is built entirely from natural elements. “How can these companies talk about development if what they have brought to other places is division and pollution,” this daughter of an ex-isolate is indignant, criticizing that those who end up profiting at the expense of the territory are people who do not live there.

The perennial problem with greed

In the main square of Iquitos, the capital of the Amazonian region of Loreto, stands an iron house designed by Gustave Eiffel and transported from the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1890, when the Peruvian town — today the largest in the world without road access — epitomized the boom in rubber exploitation. Right next to the Casa de Fierro stands the stately but decadent Casa Pinasco, the surname of another rubber magnate. It is no less than one of his descendants, a property developer, who is leading a nationwide campaign against the Escazú environmental treaty. He denies the documented existence of isolated peoples and advocates lifting legal protections for their territories — a bill to this effect was stopped in extremis this June.

From the opposite side of the square, a man from León with thousands of kilometers of Amazonian rivers under his belt observes the vestiges of a history that seems to be repeating itself. On his coffee table lies a public document the weight of a phone book, its topic: half a century of oil spills in oil lot 192, in northern Loreto. The Catholic Bishop of Iquitos Miguel Ángel Cadenas, is known for defending the dignity of neglected communities affected by the irresponsible extraction of resources. Now, he is also fighting to vindicate the right of isolated indigenous peoples to life without contact. “Greed was, and still is, very evident in the Amazon.”

You can follow PLANETA FUTURO on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram< /i>, and subscribe here to our ‘newsletter’.