Republican governors weaponize immigrants, sending them to vice-president’s home in DC

Texas Governor Gregg Abbott has been sending buses full of Latin American migrants to the nation’s capital, in a publicity stunt to blame the federal government for an increase in border crossings

It is Thursday, October 6. The digital clock outside of the Naval Observatory – the most precise clock in the United States – reads 6.14am. The sun has still not come out when a bus carrying 41 migrants – 11 of them children – parks at the gates of US Vice-President Kamala Harris’s residence.

This group was sent from the Texas-Mexico border. One person is Cuban; the rest are Venezuelan. The Secret Service agents who guard the residence are watchful, but they don’t flinch. For them, this has become a familiar scene.

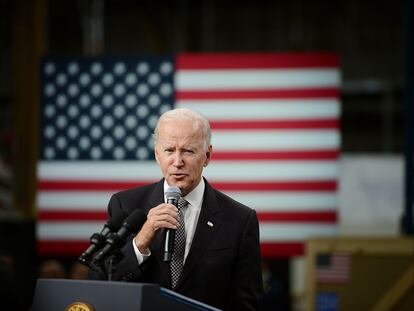

Since September 16, Greg Abbott – the Republican governor of Texas – has been sending busloads of undocumented immigrants to northern cities and states that are led by Democratic mayors and governors. This is his way of denouncing the immigration policies of the Democratic Party and the Joe Biden administration – and a clear strategy to boost Republican poll numbers before the midterm elections in November.

Governor Abbott is playing on comments that VP Harris made earlier this year, when she said that the Southern border was “secure.” With Border Patrol agents having intercepted more than 2.1 million individuals since January – a 24% increase from 2021 – Abbott decided to send migrants to the Vice-President’s doorstep in the elegant Embassy Row neighborhood of Washington D.C., on the same grounds as the Naval Observatory.

On Thursday, the latest group of shivering, tired travellers emerges from the bus after a 1,700-mile journey. Many of them are wearing sandals – their shoes were confiscated when they reached US soil. Other possessions were also seized by the Border Patrol, and they carry what little they have left in plastic bags, which they press against their bodies. Nothing has prepared them from the autumn cold of the East Coast.

Volunteers from the non-profit group SAMU First Response greet the migrants. They use minibuses – on loan from the city – to transport them to the train station, on the other side of the city.

At the station, the individuals provide their information and are given food. After a meal, most take a bus or train to New York, their final destination.

“Many of them have family or friends [in New York City]… or they go because there are more employment opportunities there,” explains Orlando, one of the NGO’s workers.

The group of new arrivals includes eight members of the Pacheco family – 39-year-old Jonathan, 42-year-old María, their four children, their daughter-in-law and grandchild. They left their home city of Ojeda, in the Venezuelan state of Zulia, six months ago. After a short stay in Peru, they decided to head north. This has been a common pattern among many Venezuelans fleeing the repression and crumbling economy of the Maduro regime – they try to build their lives in countries like Colombia or Peru, before trying their luck in the United States.

“We sold the little that we had and started walking,” says Jonathan Pacheco, “for days and nights, in the rain.” The family traversed the Darién Gap – the watershed that separates Colombia and Panama – which has become a dangerous migration route that sees tens of thousands of people passing through each month. Panamanian authorities explain that, in August, 30,000 migrants made the crossing. More than three-quarters were Venezuelan.

Once migrants reach the United States, Border Patrol Agents confiscate everything, from toothbrushes to cellphones. “We haven’t brushed our teeth in four days,” says one of the Pachecos’ teenage boys. Beside him, his father touches a bruise on his chin – a “coyote,” or human trafficker, hit him with the butt of his gun during the journey. No members of the Pacheco family speak a word of English.

In September, the Mayor of the District of Columbia, Muriel Bowser, declared a public emergency. She created an office to oversee migration services, with $10 million in funding. This has helped address the needs of more than 9,400 migrants who have been sent to the nation’s capital by Republican governors like Abbott in Texas, or Ron DeSantis in Florida.

The migrants who decide to stay in DC are divided into two groups. On one hand there are single men, who account for about 60% of all irregular border crossings, and who are assigned to shelters in the area with the help of Matthew Burwick. Burwick is a Venezuelan activist with ties to the team of opposition leader Juan Guaidó, who is recognized as the legitimate president of Venezuela by the American government. Burwick says that, when there aren’t enough shelter spaces, many of these newly-arrived men often spend their first night sleeping in the streets.

The other group of migrants is made up of families with young children. They stay in a shelter in Rockville, Maryland, for up to three days. Tatiana Laborde – the executive director of SAMU First Response – explains that, with the help of other non-profits, these families “enter the system.” Thus begins a years-long process to obtain residency and asylum status, which only the luckiest will obtain, usually through costly legal assistance. In the meantime, they make a living working jobs in the underground economy.

Laborde says that the overwhelming majority of new arrivals are from Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba. They represent 41% of all border detentions (followed by Mexican nationals at 34% and people from the Central American nations of Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador.) This dramatic increase has been caused by the economic and political conditions in the three authoritarian states. As the American government does not maintain diplomatic relations with Havana, Caracas, or Managua, individuals fleeing these countries cannot be deported easily.

Governor Ron DeSantis of Florida – who is expected to run for the presidency in 2024 – has also ignored the humanitarian situation. Mimicking the Texas government, he’s been using public funds to transport migrants by plane to Democratic-led “sanctuary cities,” like the exclusive Massacchussetts community of Martha’s Vineyard, in a play for hard-right voters who want to see deportations stepped up. Civil rights groups have filed lawsuits against him for using human lives as political pawns.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.

More information

Últimas noticias

Most viewed

- Sinaloa Cartel war is taking its toll on Los Chapitos

- Oona Chaplin: ‘I told James Cameron that I was living in a treehouse and starting a permaculture project with a friend’

- Reinhard Genzel, Nobel laureate in physics: ‘One-minute videos will never give you the truth’

- Why the price of coffee has skyrocketed: from Brazilian plantations to specialty coffee houses

- Silver prices are going crazy: This is what’s fueling the rally