Son of notorious paramilitary leader wins seat reserved for victims of Colombia’s armed conflict

Jorge Rodrigo Tovar, whose father ‘Jorge 40′ confessed to more than 600 crimes, has secured a spot in Congress – a victory many consider a slap in the face for the peace process

Jorge Rodrigo Tovar was seven years old when his father, Rodrigo Tovar Pupo, walked out and headed into the mountains. His absent father would go on to become “Jorge 40,” one of Colombia’s most feared paramilitaries. On one occasion, Tovar Pupo’s armed group is said to have seized a small village on the Caribbean coast and killed dozens of men, women and children in cold blood. They played soccer with the heads of the deceased and played vallenatos, a popular type of Colombian folk music, to drown out the sounds of the victims.

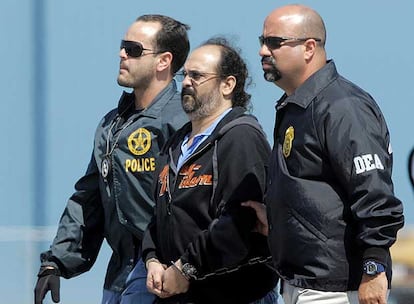

Tovar Pupo and his son were born in Valledupar, a city in northeastern Colombia. In the surrounding rural areas, entire families were murdered – in many cases by Jorge 40, who was sentenced to four decades in prison for an endless list of crimes. When he surrendered in 2006, during the process to disband paramilitary groups led by then Colombian president Álvaro Uribe, he confessed to more than 600 crimes. But it’s believed the real number could be triple that number. Two years later, he was extradited to the United States, where he spent 12 years in prison for drug trafficking – which was how he funded his paramilitary group. When he returned to Colombia, he was imprisoned again and will likely die behind bars serving his sentence.

But this year his son, Rodrigo Tovar, popularly known as Yoyo, ran as a candidate for one of the 16 seats in Congress that are reserved for victims of Colombia’s 50-year-long armed conflict. This was one of the agreements included in the 2016 peace agreement between the government and the FARC guerrillas. For the victims of the guerrilla violence, this was their moment to enter politics and share what they had suffered. The fact that the seat was won by the child of one of the bloodiest paramilitary figures is considered a slap in the face.

“It’s ethically and politically unsustainable,” says journalist Diana López Zuleta. “He [Yoyo] can claim there is a distinction between his father’s responsibility and his innocence. But to go from there to representing victims in a region awash with blood due to his father is upsetting and revictimizes [the victims].”

What’s more, Yoyo Tovar also won thanks to the armed groups that followed his father, according to López Zuleta. The politician was able to reach the remote communities that his father had terrorized back in the day. And in his constituency, he was the most-voted candidate. But the rest of the candidates, from a left-wing and activist background, were not able to reach these areas, as the roads that lead there are controlled by armed groups who consider Jorge 40 a legend.

Despite his father’s bloody past, Yoyo Tovar, however, considers himself a victim of the armed conflict. He is listed as displaced on the Colombian victims’ registry. He says that FARC guerillas wanted to kill him for being the son of Jorge 40 and he had to go into exile. He is also a supporter of the 2016 peace agreements. In this way, he argued he had the right to stand for one of the seats reserved for victims.

But Yoyo Tovar is also still in close contact with his father, often visiting him in prison. “Due to the glass [separating prisoners from visitors], the hug that we haven’t had for 20 years ago remains elusive,” he says. “He is my father, beyond Jorge 40.”

This is not the first time Yoyo’s political activities have stirred controversy. In 2020, he was chosen by Colombian President Iván Duque as the national coordinator of the Victims Group and was awarded for his work. Many thought authorities had appointed a wolf to look after the sheep. And now, he will be doing so from Congress.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.