The lost border in the jungle

The dictionary definition of the Spanish word “selva” is not just limited to “jungle,” but also encompasses confusion, conundrum. Those terms also define the Guatemalan department of Petén. The territory shares more than half of its border with Mexico, and practically the entire border with Belize. The jungle occupies the majority of this territory. Since 1998, the US Drug Enforcement Administration has considered it to be a key corridor for drug smuggling. Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán came through here, and massacred members of the Los Zetas syndicate. If you ask who is in charge now in that 2.2-million-hectare jungle, you’ll get timid responses. But a journey through this immense area allows you to understand how, for years, the main suspects have been “nobodies” in this place

I. THE FEAR WITH NO NAME IN PETÉN

The old ex-cop interrupts the conversation. After speaking for 15 minutes with the compulsion of a prisoner during a family visit, he suddenly stops short and says to me and my two photographers: “Can you show me your ID?” We put them on the table of this palm-roofed bar in the municipality of San Benito. He looks at a photo, looks up, and looks at us. He does this three times in total. “You see?! You can end up being paranoid,” he says by way of explanation. Yes, there are a lot of people in Petén who are paranoid. And they have good reason to be.

The veteran ex-cop worked for more than five years in Guatemala’s anti-gang unit. He brags about knowing the leaders. When he talks about Aldo Dupié, the best-known leader of the Barrio 18 gang, he calls him by his nickname of “Lobito,” the little wolf. Dupié has been locked up for the last 20 years for crimes such as extortion and homicide, and was sentenced to nearly 200 years in jail. But that was not when the police officer threw in the towel.

After chasing gang members, the former cop went on to work in video-surveillance operations. “They couldn’t see me on the street,” he explains about his transfer to a police base. “They would have killed me.” But he carried on.

In 2012, he was sent to work in Chiquimula, which borders Honduras and El Salvador and was one of the most conflict-ridden departments of Guatemala at the time. This was back when the Mexican crime syndicate Los Zetas was fighting with many of the Guatemalan drug families over the control of territories. At that time, Chiquimula nearly tripled the national homicide rate, which was 34 for every 100,000 inhabitants. “They left bodies for me everywhere,” he recalls. But still he continued.

They transferred him to intelligence, and then to criminal investigation. “Practically everyone there had me in their sights,” he says, gulping down his beer, his white shirt soaked with sweat. The garment is dripping as if it were a soggy sponge, and every movement of his body appears to be a hand that is wringing it out. By that point, he suspected that both criminals and his colleagues in the police wanted him dead, so he requested a transfer in 2016. “And they sent me to Petén,” he says, forcing out a bitter laugh. “They looked at me like I was an ogre,” he says. “Think about it, I came from intelligence…”

It wasn’t because of the gangs, nor was it the investigations into drug traffickers in the capital. It wasn’t even the wiretaps that implicated the police in criminal activities, nor Los Zetas in Chiquimula. The reason that this police officer decided that his organization was trying to kill him was because they sent him here, to Petén. That was when he quit.

The ex-cop finishes reciting his problems with the police force that he walked away from a couple of months ago, and now he answers my questions about Petén, with another beer on the table. But we enter a dead end. In this jungle-filled department that borders with the Mexican states of Tabasco, Chiapas and Campeche, the biggest one in Guatemala, the answer is always the same, no matter who you ask: “You can’t go there.”

“We are thinking about going to La Pasión river,” I say, in reference to the tributary that connects Guatemala with Mexico and has been used for decades to transport drugs and migrants.

“Not advisable. They’ll kill you,” he responds, pulling a face with his jaw sticking out and his eyes wide open in an attempt at drama.

“We also want to go to the communities within the protected reserves, Lacandón and Laguna del Tigre.”

“If you are not from there, they are going to snatch you and there will be a negotiation to free you. They held me for half a night or so once, when I made some arrests in the wetlands of the El Coco community.”

“We can’t leave without going to Bethel,” I say, exhausting all possibilities by mentioning a village where migrants cross, close to Frontera Corozal on the Mexican side.

“Look, too much scrutiny here is dangerous,” he says, tired of answering questions about every single place. “Life is very tough here. If you are tough, you’ll survive. If not, they’ll eat you alive.”

In Petén, everyone tells you to “stay in the center, don’t head to the outskirts, keep away from the jungle.” But the jungle accounts for 60% of Petén, 2.2 million hectares of land, 22 times the size of this country’s capital. They tell you not to go, and then recite with great detail the names of hamlets, villages and natural areas that are off limits: Las Cruces, Bethel, La Técnica, El Naranjo, the jungle. However, when you ask them what they are so afraid of, all details disappear and everything becomes as dense as the depths of Lacandón. You get the impression that they fear anyone who lives in the jungle. Yet the jungle is inhabited by a wide range of people.

“They are ex-politicians, narco farmers, ranchers, members of the military who are up to their necks in it, Mexicans who travel down here,” says the ex-cop, who is unable to pronounce a single surname in this bar. We say goodbye. Despite the misgivings he has voiced, the ex-cop says that I can use his real name in this article, and then he leaves.

He calls me the next day. “Thanks to the beers, I got carried away. Please don’t print my name, don’t leave my ass hanging in the breeze.”

In Petén, mystery surrounds the way into the jungle. But even more of a mystery is just who is in charge down there.

The plane with the torn bags

A plane came down in the outskirts of Sayaxché on April 13. It didn’t quite manage to reach the jungle and land on one of its runways. It crashed instead on the margins of this municipality in the midlands of Petén, and ended up with its nose buried in a ditch outside a village called Sepens.

It’s not unheard of. It was the second plane to fall that month in Petén. The other one, with a Venezuelan registration number, did manage to make it to the jungle on April 7, but crashed in the depths of Lacandón. The one that came down in Sayaxché had had its registration number removed.

The community is around 20 minutes away from the center of this municipality, which is on the banks of La Pasión river. Sayaxché is a symbol of how Petén has been neglected. In the middle of the jungle and the enormous plantations of African palm there are 13 municipalities. The majority of them are villages with suitable infrastructure: dirt roads, a few that have pavement, street markets, a man with a microphone who reads out the news and Tuk Tuks that weave among the pedestrians. The municipalities that are more modern, such as San Benito or La Libertad, are near the capital, Flores, a tourist destination where foreign travelers stay while visiting the Maya ruins. These places have the odd mall and fast-food restaurant, and that’s where their city traits end. Sayaxché is different. It has none of that.

Sayaxché, like Petén, is so far removed from the rest of Guatemala that no one here talks about the Barrio 18 or Mara Salvatrucha 13 gangs. They are not a problem around here. There are bigger beasts in the jungle. There are studies that talk about groups linked to drug trafficking that exterminated gang members who tried to create their own subgroups in at least three municipalities: Poptún, San Luis and, of course, Sayaxché.

The best way to illustrate that Sayaxché is living in another time is the fact that in order to enter and leave, you need to get on a kind of raft to cross La Pasión river. To call it a “ferry” would be an exaggeration. It’s a floating platform made of wood and iron, which floats thanks to some barrels and is propelled by two 75-horsepower outboard motors. This raft, which looks like something from a post-apocalyptic science fiction movie, can fit 10 cars. It travels the 100 meters back and forth 24 hours a day.

Different governments have been promising a bridge for years, but everything suggests that they’d rather leave Petén as it is: marginal, rural, and forgotten about.

The plane came down about 10 kilometers from the bustling center of Sayaxché. But there is nothing left of it. Two weeks later, soldiers had come to remove the fuselage.

The report of what happened is simple: a plane crashed at 2am. Two bodies ended up scattered about the place. The soldiers arrived at around 8am and took control of the scene.

Too simple for Petén.

Rony Bac, who is from Petén, was one of the journalists who arrived in Sepens that day. As his photographers corroborated, the plane’s registration had been scratched off. Among the fuselage, there were three torn bags, all of them empty. There were also five barrels that smelled of gasoline, according to Bac. The bodies had the pockets of their pants ripped at the bottom, as if someone had cut them with a knife. There was no documentation nor any cash. “All of the plastic bags with food and the sodas were Mexican brands,” he says. Bac got there at 9.30am, 90 minutes after the soldiers and seven and a half hours after the accident.

The story is still too simple for Petén.

Another journalist from the area meets with me at a diner in Sayaxché. Before he starts talking, he has a warning. “Wait. Look behind me, I’ll explain it to you.” Two portly men have finished their breakfast and they get up from their table. “They’re from the Segura family,” the journalist explains. “They are the most powerful family here.” The Seguras, who are known to many police officers and journalists in Petén as the Sayaxché Cartel, have a history that is worthy of a TV narco drama. On April 1, 2003, the patriarch and then-mayor of Sayaxché, Guillermo Segura, was murdered in the parking lot of town hall by men wearing goat horns. The bullets also killed a local gardener. A week later, the prosecutor assigned to the case and his bodyguards were shot at in the south of the country. They survived. A year later, the sons of the deceased mayor, Jonny Javier and Ricardo de Jesús, were also assassinated. Their bodies turned up with signs of having been tortured. “It was all about the theft of some drugs that came in a plane. They stole it from the Golfo cartel,” the journalist explains once the relatives of the dead men have left the diner. Days later, another journalist gives me the same account. Neither of the two reporters published a single word about what happened. Other members of the Segura family have been killed, while others have run as candidates for mayor of Sayaxché.

Returning to the last plane that crashed, I ask the journalist to guide me to the area where it came down. He smiles as if amused at an idea from a child.

“You can’t. It’s all very tense down there. They have killed several people who sold what they made off with.”

The impossible question in Petén is back on the table. “Who killed them?” The reply to that question, in this jungle-filled department, usually begins with the words: “They say…”

“They say that the drugs in the plane were from a Mexican cartel, but I don’t know which one,” he answers.

What is known in Petén – albeit not very well – is what happened years ago. People who were killed back then are named. What’s happening these days is neither known about nor talked about. And that is having an effect on the national level for this enormous department. In the capital of the country, two former prosecutors, an ex-civil servant and three police chiefs told me that entering La Pasión river from Sayaxché would mean certain death. “You can get in there all right, but getting out alive is the problem,” I was told by Mauricio Bonilla, then the interior minister, in June 2014. Even from the capital they refuse to govern this region. A number of the big bosses owned ranches nearby, and even improvised boatyards, but that was a long time ago. Those were figures like Juancho León, a known boss who was killed by Los Zetas after a shootout in March 2008. The planes and the traffic through the jungle substituted the route via La Pasión and now you can travel to the military post in Pipiles, the last before entering Mexico, without too much trouble.

The reality of what is happening in Petén is told with a time delay. The city is always late to find out what is happening in the jungle.

After the last plane came down, the police in Petén accused the military – who were the first on the scene – of being behind the emptying of the bags and the pockets of the bodies. The soldiers denied it. The inhabitants of the Sepens community said that they had seen the military leave there with things. The national press echoed what the locals had said. “Soldiers on board pickups loaded up and took away a number of boxes and white bags,” they reported. The military still denies it. Many in Petén, in whispered voices, ask who could have stolen what was in the bags. No one asks who the bags belonged to.

Avoiding asking certain questions is something of a local trait.

This is not the border for small-time drug dealers. This is the border for cartels. Here, trafficking does not happen on foot – it comes from the skies or opens up paths in the jungle. Petén occupies more than 500 kilometers of the 965 of the border shared by Mexico and Guatemala. On top of that, Petén occupies almost the entire Guatemalan border with Belize: 212 kilometers of nearly 250.

This land is not unknown to big-time drug traffickers. In February 2013, the Mexican and Guatemalan governments opened an investigation to find out whether one of the bodies that was left behind after a shootout in the Petén municipality of San Francisco, near Sayaxché, was that of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. “It could be him,” the then-interior minister of Guatemala, Mauricio López Bonilla, said at the time. He later clarified that it was someone “very similar to El Chapo” who had died in a confrontation with the authorities. The idea that one of the world’s most-wanted drug traffickers was in Petén was not a crazy one. In the previous days, WikiLeaks had revealed an email sent by an analyst at the US security and intelligence consultancy firm Stratfor. “We believe that El Chapo is currently hiding in El Petén, close to the border with Mexico,” the mail read. “Since 2006, Los Zetas and the Sinaloa [cartel] have dismantled the existing cartels in the north of Guatemala and taken their place,” the message also read.

This is the border via which Los Zetas entered into Guatemala. This is where they carried out the worst massacre in the country’s living memory. In May 2011, 12 vehicles arrived in the border area of El Naranjo, each of them carrying 50 men with rifles and under the command of someone who was called Kaibil, the name of the elite soldiers from the Guatemalan army, who have been accused of a number of atrocities. When they left, there were 27 laborers chopped into pieces in Los Cocos farm, in La Libertad. There were 25 men and two women. One of the bodies still had its head. Twenty-six were decapitated. Twenty-three of the heads were left behind by Los Zetas on the land; three of them never appeared. The laborers had arrived at the main house to pick up their weekly paycheck. Their remains were discovered by locals who wanted to buy cheese and cream at the farm. Los Zetas left painted messages threatening their real target, the farmer Otto Salguero, who was accused of stealing a shipment from the Mexican cartel. According to the public prosecutor, they wrote those messages on the walls in blood. They used a leg as their brush. They signed the inscription with the name of the cell: Z200.

“Here, in Petén, it’s complicated to say who is involved and who isn’t. It’s better not to know. It’s risky just to ask. And the further you get from the towns and the closer you get to the jungle, it’s even worse,” says another journalist, this time in a different diner from the the one where the Seguras were having breakfast. On finding out that we had met with his colleague at the previous diner, he asked to meet with us in another one, further away. That contagious fear has taken root here with memories such as the massacre in Los Cocos. It is the paranoia about which the former policeman spoke in that palm-roofed canteen.

“We want to go to Sepens to see the plane that came down,” I tell the journalist.

“A newspaper article is not worth dying over,” he responds.

I call up Colonel Óscar Pérez, the press contact at the Guatemalan army. I ask for the contact details of the chief in Petén and for permission to take a tour with them. I plan on telling them that we should go to Sepens. “No one apart from the Defense Ministry or I can make statements and I cannot authorize any tours in Petén,” he replies. “I can tell you right now, that is impossible.”

The closest I will get to Sepens is a phone call with a man who has two brothers in the community. He says that they are all “in a state of fear” over there, and that the plane that came down on April 13 was carrying bags of cocaine. In fact, in the photos of the fuselage you can see that all of the seats of the plane, which has capacity for 12 passengers, had been moved and were disheveled, apart from that of the pilot and the copilot. More bags and barrels than those that were found on the scene would fit inside.

“People from the community took packages away with them,” the man explains. “There were a lot of idiots who went crazy and sold off a kilo to people from Sayaxché for 10,000 quetzales each [around $1,300 or €1,165). Two days after the accident, armed men arrived with lists of people who had taken the packages. They already knew. They were carrying rifles. Around 15 families have already left Sepens. Others have buried packages and don’t know whether to flee or to return them. The village is in a state of panic, because those men are still circling looking for what’s theirs.”

“Who are those armed men?” I ask.

“No one knows,” he answers via telephone.

“Can you help me get into Sepens?”

“No, no I can’t.”

A Hummer headed for Bethel

It gets to the point in Petén when you need to start ignoring things in order to understand.

If you stick to the advice from the authorities, organizations and journalists, you’ll end up trapped in the urban center of the department – not the heart, because that is in the jungle. You end up forgetting about the reserves, the villages and the border. You forget to understand.

The jungle is the home to a mystery, and many seem keen to keep it that way.

We head to Bethel with our photographers.

If the inappropriately named Sayaxché “ferry” speaks to abandonment, the dirt road in Las Cruces speaks to neglect. This is the newest municipality in Petén, located right in the middle. It was born in 2011, when La Libertad was split up. The municipality is basically whatever is close to that gap, which is dusty when it’s not raining, muddy when it is. The divide snakes from the road that joins Sayaxché with La Libertad, to the foothills of the Sierra de Lacandón National Park, which is in the jungle on the border with Mexico.

At the end of that wedge, 100 kilometers away, is Bethel, the River Usumacinta and Mexico.

On the way to Bethel you find other little villages, such as Palestina. Some of the houses sport cable TV antenna, and there is also a pharmacy, a farm shop and little houses that function as the headquarters of political parties. Minibuses drive around packed with migrants who are seeking to cross the border. Bethel has been a crossing point since at least 1987.

An H3 model Hummer, one of those that costs around $12,000 in the US auction market, whizzes past us at high speed.

On the way to Bethel, you pass Las Cruces, which is the center of this unpaved municipality. In the Petén catalogue of “you can’t go there,” Las Cruces figures high on the list. The former cop, a mayoral candidate in the area, a health worker, the madame from a brothel and a one-time public prosecutor all gave us what is becoming well-worn advice in Petén: don’t go there.

Here in Las Cruces, for example, Efraín Cifuentes was caught back in November 2014. Known as “El Negro,” he had been sought by the local, Mexican and US authorities since 2009, for having coordinated shipments of cocaine from Honduras to Mexico using this route. The authorities, however, could not agree on who he was working for: some said Los Zetas, others cited Los Caballeros Templarios and the infamous Sinaloa cartel. Perhaps, the public prosecutor argued, he was working for all of them, given that men in his position have often operated as free agents.

The Guatemalan Defense Ministry said that El Negro would smuggle two weekly shipments of 100 kilograms of cocaine. He did so using speedboats and trucks, and he would deliver them in the Mexican community of Benemérito de las Américas, on the other side of this mountain and river border, a prelude to the jungle. The operation to capture El Negro lasted 48 hours. There was a confrontation with his six bodyguards in Las Cruces, but they fled upon seeing the police and military there. The bodyguards escaped toward the jungle. El Negro, however, was too fat to run and was captured, rifle in hand, in the patio of his home.

The black Hummer has stopped. The driver, a man with a cowboy hat and boots, urinates against a tree. When he sees us coming around the bend, he runs to his vehicle and speeds off.

Bethel is a village of 196 families that are scattered around the banks of the Usumacinta.

“We live off the mojados [undocumented migrants] and agriculture,” says the community leader, William Mérida, who has spent 52 of his 67 years in this corner of the globe.

“So, what do you show journalists when they come here?” I ask.

“Journalists? Here? Never,” he answers with a laugh.

The transit of migrants through Bethel is as natural an event as the sunrise. This is not the United States border. There are no walls or border patrols here. The hard part is not crossing into Mexico, but rather making your way through that country without being raped, kidnapped, assaulted or extorted by drug gangs, police, migration officers, thieves or common rapists.

“That man who lives there is the coyote,” Mérida explains, in reference to a guide for undocumented migrants.

In the river, a group of eight migrants – two children among them – are bathing, and with an improvised hook, are trying to pull a few fish out of the water.

“They’re waiting their turn,” Mérida explains. “We live off them, from selling them food or whatever we can.”

This is the area where the coyotes cross. They usually wait until their “line” is active in Mexico before they cross. “Line” is what they call their network of contacts with criminals and migration officers who will let them cross without problems, once they have shared out the profits. It’s normal for a coyote to wait a couple of days until their contact in immigration is in charge of the gatehouse where they will have to pass when they leave the mountain for the road and the route is no longer taken on foot.

“Are there problems here with the drug gangs?”

“Those who do stupid things end up badly,” replies Mr Mérida, putting his index finger to his lips.

Many migrants cross through Bethel. Others who are part of bigger groups cross closer to the jungle, through La Técnica, a neighboring village close to a small dock opposite Frontera Corozal, in Mexico. Mérida offers to take us there. He’s accompanied by another community leader, Guillermo, a Nicaraguan migrant who, after having been abandoned by his coyote, has been in Bethel since 2002, and is now their health promoter.

We are moving through a road that is becoming narrower and more winding. We are on the banks of the Usumacinta, following the border. The people in the small villages on the route freeze on seeing our truck go past. The stares follow us until the necks can crane no further.

We reach a bottleneck. The Hummer is now blocking our path. Its driver, without getting out of his vehicle, has stopped to talk to three men who are parked on the road and are drinking Corona beers. Two of them are carrying guns tucked into their belts and their shirts are unbuttoned. The two cars are completely blocking the route. After a few minutes, the black Hummer continues on to La Técnica.

I ask Mérida and Guillermo if they know the owner of the black Hummer. They say no. Mérida goes quiet. Guillermo glances around, looking in all directions. He has stopped telling his story and is now the one asking the questions. “Are you really journalists? But what specifically are you working on? Why do you want to go to La Técnica?”

We decide to cut short the journey. We turn around and head back to Bethel. The armed men are still in the bottleneck.

We barely got to the fringes of the jungle and fear overtook all of us.

That’s the effect that Petén has.

II. INTO THE JUNGLE

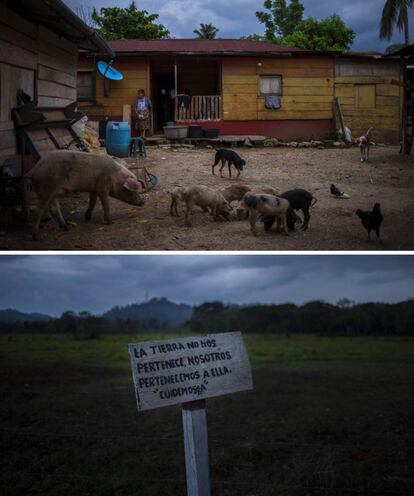

It is raining in the jungle of Lacandón. As we make our way into the protected reserve, the mud gets thick. The off-road vehicle we were riding in got mired in the soggy earth, so we are now being forced to walk to La Revancha. “Invaders,” is what the State calls the members of this community. “Drug traffickers” is how many other people in Petén describe them.

But “walking” is not the right word for the way we are advancing through the rainforest in the downpour: it is more like a cross between skating and climbing. We are still four kilometers away from La Revancha, and we have lost more than the car back at the foot of a hill known as La Señal, or The Signal. That’s what they call it because it is the last spot with telephone reception. We now have no transportation and no way of communicating with anyone outside the rainforest.

But if reaching La Revancha is proving complicated, finding the right contacts to get inside was a veritable odyssey.

Just when the wall of fear in Petén seemed insurmountable, I started hearing other voices that began to show me, little by little, the way into the jungle.

Byron Castellanos, who is “100% from Petén,” is the executive director of Balam, an association that has been working in this administrative department of Guatemala for around a decade. Balam is officially an environmental organization fighting to preserve protected areas that are home to as many as 60,000 individuals who should not lawfully be there. There is not a single sports stadium in all of Central America with seating for that many people.

But organization leaders soon realized that in a place like Petén, natural resources are only one aspect of a tangled web that also includes poverty, abandonment by the State and organized crime. Castellanos spells it out the instant he starts to talk: “We are not an association working to save little birds and trees,” he says. “We took a look at the little birds and then asked ourselves ‘Why does the forest come to an end?’ And that’s when the complicated part began.”

The complicated part, to brutally summarize what took Balam years of work, was realizing that the goal was not to evict the poor, but to show them how to coexist with the jungle. The complicated part was also understanding that inside the jungle, there are not just poor people but also land owners (finqueros). And that for years, the State has been cracking down on those appropriating a little bit of land out of desperation, while ignoring the large landowners who use up hundreds of hectares. “The biggest crime in Guatemala is being female, indigenous and poor,” says Castellanos.

“In Lacandón there are 50 communities that have been left to their own devices for the last 50 years or so along this border.” A lot has been said on the topic. But Castellanos is also aware of the other part of the picture: “Light aircraft land around the [military] camps. There are seven landing strips in Laguna del Tigre, and five in Lacandón. We do not rule out the possibility that there might be people from the Defense Ministry involved.” Castellanos’ words ring out bravely. For six years, from 1998 to 2004, he was general technical director for the government agency Conap (National Council of Protected Areas).

“Petén is a fertile territory for a perverse alliance between organized crime and poverty,” he says. This has created entire areas where the State does not dare enter. “They’ve held judges, military personnel, police officers in there.”

In September 2011, during a speech in Argentina, Francisco Dall’Anese, who then headed the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) created by the United Nations in 2006, said that in Petén nobody was acting against the real drug traffickers. He also told the story of how a UN high commissioner was headed for Los Cocos ranch to report on the massacre of 27 peasants when he was stopped by drug gang members armed to the teeth who subjected him to an interrogation and only let him go after a negotiation.

According to Castellanos, in the jungle the logic goes like this: “First come the poor. Then comes the estate owner, and the poor either work on his property or they go occupy some other place.”

I ask Castellanos the question that nobody in Petén has been able to answer so far. His reply is the most accurate statement I have heard on this entire trip.

— Who are these land owners?

— We are in a process of transformation. They shared out the pie. We have small-time drug traffickers born out of the collapse of the bigger ones.

They are known to be there, but nobody knows who they are. The jungle is still keeping that secret, and for years the official message has been that the indigenous communities are the drug traffickers.

In 2011, after the massacre at Los Cocos, several international organizations showed an interest in this border land. That’s usually the way it is in these forgotten corners of the Americas: a lot of people have to die in a single day for the world to take a look.

That year, a report came out that was funded by the Soros Foundation. The authors, academic researchers from several countries, did not sign their work out of fear of reprisals, and when they granted me an interview it was through Skype and using digital security tools that made it impossible to find their location. The fear of Petén had rubbed off on them. Their report analyzed power relations in the region, and also provided incontestable data regarding land ownership by drug trafficking families such as the Leóns, the Lorenzanas and the Mendozas, all of whom have members who have been extradited to the United States. In total, according to the report, these families owned 1,179 caballerías (the equivalent of over 53,000 hectares) in Petén. And it was quite shameless: some of that land was located inside Laguna del Tigre National Park, and one of the properties on it was registered to the name of the patriarch Waldemar Lorenzana, who was extradited to the US that same year. His name appeared on Guatemala’s public property register. The maps also showed mansions, one of them with a swimming pool and a landing strip in Lacandón, which were part of a series of fenced caballerías extending right up to the natural border with Mexico, the Usumacinta river.

Right now, says Castellanos, his organization does not work in the border lands inside the protected areas. “If I send in my people, they will get killed. Let the State go in first, but for real.”

As a reporter, in order not to get stuck for information in Petén, there is one essential rule to follow: walk out of each interview with a new contact. Castellanos gave me one who gave me another one who gave me another one who finally led me to Elbia García, a mayoral candidate in La Libertad for the Vamos (Let’s Go) party. This retired schoolteacher is the only female nominee to a position that is being sought by 13 men.

We meet in El Naranjo, right on the fringes of Laguna del Tigre national park. Among Central American migrants, El Naranjo is known as Guatemala’s own Tijuana. This is a tiny place that is no match for the Mexican border town, except in aggressiveness. During a walk that lasts under 10 minutes, we see five armed men with their guns in plain view. Some of them do not look as though they are trying to defend themselves from attackers, but rather as though they were going to participate in a shootout: one of them walks down the street with his 9mm pistol and two additional magazines hanging from his belt. That means around 50 bullets at his disposal. This is the last village where one can obtain supplies before crossing into protected land. Beyond lie the blind spots of the rainforest.

García is the only candidate who has visited communities such as La Revancha. She demands guarantees for them: “Land, the security that they are not going to be moved out from there. A peasant takes up no more than three of four manzanas (one manzana is 1.72 acres). Yet the State attacks the peasants. But it’s the finqueros, the businessmen.” And then she says no more.

— Who are those businessmen?

— Powerful people. They are armed individuals. But it’s better not to talk about that.

Petén again.

This García knows another García: Rubén García, who is the deputy mayor of El Paraíso, the last officially recognized village before entering the rainforest and the mud on the way to La Revancha. Rubén holds the key to going in there. He knows the residents, because as official of this community he feels that he also represents those who moved into the jungle.

Rubén, 39, is a friendly, sturdy-looking man who speaks unhurriedly. He is waiting for us in the village to travel together to La Revancha. Elbia García, the mayoral nominee, is coming along on the trip.

We are finally on our way to the place where everyone advised us not to go. The place where it is said that all the evils of Petén reside.

As the vehicle skids in the mud, Rubén keeps talking: “It will soon be 12 years that La Revancha has existed. Back during the war [1960-1996], there was nothing but guerrillas in those mountains. Then came the chicleros [who extract chicle, a natural gum, from trees] and the loggers. They paid a fee to the guerrillas. Then people looking for land began arriving here from all over the country. The guerrillas did not let them stay, but the peasants came back anyway. When they returned for the third time, when the war was already over, they said: “Let’s get our revenge [in Spanish, la revancha].”

Life in this rainforest predates the law, quite literally: there are communities that have been living in Lacandón and Laguna del Tigre since the 1970s. Many more arrived in the 1980s. The Protected Areas Law was passed in 1989.

For a couple of kilometers, everything is green. The mountain is green and the forest is thick. The howler monkeys do honor to their name. But after a bend in the middle of the hill, we suddenly see a stretch of burnt forest covering the equivalent of around two manzanas. The jungle has suddenly turned black. The reason is that residents of La Revancha work on land that they pick out among the greenery, pulling everything out in order to plant their seeds. After growing maize, beans or squash, they burn the land to exterminate any remaining shoots and start the process all over again. Whoever denied that poor peasants are contributing to the deforestation of Lacandón would be lying. But this is as much damage as a poor peasant, armed with a machete as his only tool, can do. These few acres of burnt forest are the price to pay for a man to keep his family alive.

During an interview, the director of Conap in Petén, Marvin Martínez, spoke of those “businessmen” without mentioning their names: “Sometimes, a single person has more of an impact than an entire community.” He admitted that his agency had found properties encompassing as much as 1,000 hectares.

“The people of La Revancha are accused of being drug traffickers, invaders, but people can’t make a living any other way. If you go further into the rainforest you may find properties covering 50, 80 caballerías [one caballería is 44,66 hectares] that are lawfully registered. There are no laws for the wealthy, only for the peasants,” says Rubén García. “For peasants, this is a protected area, but for millionaires it is a free space,” adds Elbia García as she clings to a door handle on the vehicle, which lurches as though it were a boat being hit by waves.

A look at a satellite image of the area lends credibility to their statements. Within a 10-kilometer radius around La Revancha, there are at least three large coffee-colored stains, rectangular in shape with perfectly marked boundaries. They are around 10 times the size of the community, although there isn’t a single house inside them, just livestock land.

“This is La Señal hill,” says Rubén. “This is people’s salvation point. This is where they call from when they bring in a sick person, so we can come for them. They carry the patient to that spot with a mecapal [a waistband with two ropes used to carry heavy objects]”. The vehicle is barely getting anywhere. This is not a road, it’s a mountain.

At the bottom of the hill, the jungle turns dark again: two more burnt manzanas. At that point, the car simply gives up, and it is swallowed up by the mud.

There are still two kilometers to go before reaching La Revancha. The heat in Petén goes beyond a physical feeling: it creates a mental mood of anger, it makes one want to scream obscenities out loud.

Before getting there, a man on horseback rides by in a scene from a bygone era. He is indigenous and barely speaks any Spanish. His clothes have been fashioned from tatters. Slung on his back is a .20 caliber rifle made out of wood and old scraps of iron. Inside his matate (a bag made with agave string and used to carry food), there are two plastic bags containing a rodent known as tepezcuintle and slabs of venison. The man is leaving the rainforest to see if anyone will purchase these items. All he is asking for both is 150 quetzales (around $20 or €17,60). It will take him all day to make the round trip.

La Revancha is made up of 60 families who live in 20 huts made with palm leaves and naranjillo beams on a plain in the middle of the rainforest.

The people who we were supposed to fear seem afraid of us instead. They look at us with mistrust but no aggression. It is more like a look of fear: their heads are down, they glance at us sideways with arched eyebrows, their bodies rigid.

There are many scenes of extreme poverty.

Yolanda López, a woman in her thirties who has lived here for 14 years, asks me to follow her after confirming that I am neither a Conap forest ranger nor a member of the military nor a police officer. As she walks she repeats: “Come see where we get the water from, come, come.” We reach a hole in the ground on a hillside. A little bit of water is accumulating at the bottom of the rocky cavity. It looks life coffee, and thick coffee at that. In fact there’s more mud than water in it. To extract it, Yolanda scratches the stone with a plastic container, which collects a little bit of the dark liquid at the bottom. “This is what we drink, this is what the children drink,” says Yolanda from the bottom of the pit.

Last year, three children aged eight, four and two died. Yolanda, who is the local healer and midwife, says that they died of “fever and diarrhea.” The remedy did not work, she says. Even though they prepared a potion with vervain and bombilia (two types of plants), cooked it in cinnamon, added half a tablet of metamizole (a painkiller used to relieve fever) and administered it to the children, they died all the same. I ask Yolanda what they eat, and she and two other women list their menu: beans with tortillas and guano palm hearts, beans with tortillas and pacaya (a type of palm tree), beans with tortillas and black nightshade (another plant), or just plain beans. “Once a month we kill a chicken,” says Yolanda.

There are many scenes of misery, but one stands out above the rest. A barefoot child of around five, his feet sinking in the mud, goes from hut to hut offering people the bananas he is carrying in a container on his head. A child selling bananas in the jungle.

There is no medicine here, and no school, and no running water, and no electricity. But at least in La Revancha there is no drug trafficking, either. Nobody working in that line of business would ever live in one of these hovels.

Evaristo Pérez Alvarado, Don Quincho, was the first person to reach this spot, even before it was a community with a name of its own. He arrived here 27 years ago, on the back of a State’s promise, made in the mid-20th century, to offer peasants land to populate Petén. When he got here he found a different reality, and he went deeper into the jungle for an obvious, practical reason: “I work the land, I live off the land. That is what I do. That is what I know how to do. And so I need land.”

Don Quincho has brought 60 people together inside a galera, considered the social center of La Revancha. There are indigenous women, barefoot children, peasants wearing rubber boots.

“Raise your hand if you know how to read”, I say.

Seven people raise their hands.

“Raise your hand if you know a trade other than agriculture”.

Nobody raises their hand.

“You are accused of being drug traffickers”, I say. Many, fed up, lower their heads.

“If I was a drug trafficker I would not be here treading mud with my feet. We are here because it is better or less bad than other places we could be”, replies Don Quincho succinctly.

I ask those who know how to read to raise their hand. Seven do.

Then I ask those who know a trade other than agriculture to raise their hand. None do.

“You are accused of being drug traffickers,” I tell them. Many of them lower their heads wearily.

“If I were a drug trafficker I would not be here treading mud with my feet. We are here because it is ‘more better’ or ‘less worse’ than other places where we could be,” replies Don Quincho succinctly.

It is difficult to imagine a more precarious spot in this rainforest than La Revancha, but there is one.

In some way, La Revancha is a success story for its residents. Their first and foremost demand is to be allowed to remain there, despite the lack of everything. There are other requests that are no less relevant (water and education, chiefly), but living in the jungle and not on some piece of wasteland in a random municipality remains their main struggle. Growing food to eat, eating to stay alive. That is the simplicity of the jungle. “Only a contingent of soldiers could get us out of here,” said a man from La Revancha to me. “If they take us out, we will return,” said Yolanda. In that sense – so terrible, so Latin American – it is an achievement just to end each day after eating their own beans and going to sleep in their own huts. There are others in the jungle who do not have even that miserable good fortune.

Reaching the community of Laguna Larga through Guatemala is so complicated – two days of travel, they say – that it’s better to go through another country. It is better to go through Mexico.

Laguna Larga is a border. This is no metaphor. It is precisely the border between Guatemala and Mexico. This is not a piece of territory, it is a division line. Laguna Larga is made up of around 100 shacks at the far end of Laguna del Tigre. This is a community of people who have been accused of drug trafficking for many years.

Laguna larga

In August 2010, the Guatemalan president at the time, Álvaro Colom, promised to send troops to Laguna del Tigre and kick out all the drug traffickers occupying land. “For September 15, I have ordered the Army to enter and take Laguna del Tigre. Goodbye to the drug dealers and their cattle. They’ve threatened me, but I’m not afraid of them. They hate me, but I will not take a step back. I don’t want to see a single head of cattle, because I am going to quarter it and share it out among the poor,” he said.

Nearly a decade later, there are still a lot of poor people in this jungle and a lot of cattle that does not belong to those poor people.

Laguna Larga is not even the real name of this inhabited piece of border land, but of another bit of jungle that they were evicted from earlier. On June 2, 2017, 1,400 police officers and 400 soldiers entered Laguna del Tigre and reached a body of water known as Laguna Larga (Long Lagoon) that was surrounded by a few wooden homes built by peasants in the early 1980s. The nearly 500 residents had fled a few days earlier, and in some cases just hours, leaving in small groups after hearing that the soldiers were on their way. Many of them, especially the indigenous members of the community, still remembered the days when the military would show up to eliminate anyone considered a subversive. Nearly 500 people fled through the rainforest in the direction of Mexico and spent the night out in the rain, on the border with the Mexican state of Campeche. And that is where they have been ever since. They still call themselves Laguna Larga, except they are no longer located near any lagoon.

Getting there from Guatemala involves crossing the entire Laguna del Tigre national park, which is as unrecommendable as going for a stroll in Mexico’s Golden Triangle (the region that covers parts of the northwestern states of Chihuahua, Sinaloa and Durango). The best way to get there is to cross into Mexico, then travel for several hours by road along a line running parallel to the border. As though reality were being sarcastic, the hamlet that comes before Laguna Larga is named El Desengaño (The Disillusionment). This is where we wait for Servelio, the leader of Laguna Larga.

After two kilometers along a dirt road, one reaches the border, a flat line that is easy to identify. It is as though someone had combed the jungle with a gigantic rake. On that line, along a stretch of some 500 meters, looking like an improvised refugee camp, there is a community of 500 people, including 200 children.

If the dwellings in La Revancha could be described as huts, these do not qualify. Bits of trash have been used to construct these homes: plastic sheets, wooden planks, a section from a sun umbrella.

Also unlike La Revancha, there is no land here. On the Guatemalan side, the soldiers remained stationed at the lagoon to make sure these people did not come back. On the Mexican side, the authorities will not let them settle down in their territory. They are people without a country: they cannot cross back into Guatemala because the area is a protected natural reserve; they cannot move forward into Mexico because it is not their country. In order to survive, they take a few steps into Mexico and lease land from the residents of El Desengaño. The price is 1,000 pesos (around $50 or €46.50) per hectare. A good crop yields around 500 kilos of produce. Each kilogram sells for four pesos (20 cents of a dollar or 18 cents of a euro). In other words, 2,000 pesos if they’re lucky.

At La Revancha, people harvest crops to eat. At Laguna Larga, people harvest crops to see if they are good and they are able to eat.

“Land grabbers, mountain loggers, heritage looters, drug traffickers, timber smugglers, dangerous terrorists,” says Servelio angrily as he lists all the things that the authorities have said about them. “And we are just peasants.” When he talks about that night in 2017 when they first huddled with their children under the rain in this vile place, and when he remembers the next day, seeing the smoke billowing over their homes which their soldiers had set on fire, Servelio cries.

Venturing into Lacandón and Laguna del Tigre did not offer me a chance to meet the drug traffickers, but I did meet people who are not, despite years of accusations to the contrary. In order to find the great landowners of the rainforest, it is not necessary to sink your feet in the mud. There are satellite pictures of large fenced properties covering thousands of hectares. These images and the pictures of clandestine landing strips captured from the air have been in the public domain for decades. In 2004 Prensa Libre, Guatemala’s main print newspaper, ran a front-page story titled Tierra sin ley (Lawless land) that described Laguna del Tigre as a “drug dealer paradise” and talked about 15 aircraft that had been destroyed by the drug lords themselves at various moments. In June 2017, Plaza Pública published a feature titled Temporada de desalojos en la Laguna del Tigre (or, Eviction season in Laguna del Tigre). The reporter participated in an air and land reconnaissance mission during which he saw “large fenced properties, trucks filled with cattle, mansions with ostentatious porches.” And just 25 meters from an oil well owned by the company Perenco and six kilometers from a military camp, he saw a clandestine landing strip.

Up from the air one can see that there are landowners in the jungle. Down on the ground one understands that there are also people trying to survive.

A woman stops me as I am walking through Laguna Larga. She asks me to go inside her champa (shack), then tells me about her problem and asks me for a favor. She says that her husband left Laguna Larga a month ago in a bid to reach the United States as an undocumented migrant. He was caught in Calexico, California. For a week she walked every night to El Desengaño, where there is telephone reception, to wait for his call. Two days ago, the call arrived. He said he’d heard at the detention center that some people are granted asylum if their lives are at risk back home. That is the favor that she is asking me: “You are a journalist. Take a picture of this place and send it there so they will let my husband go. Send them proof that we are very poor and don’t have enough to even eat.” I explain to her that asylum is not granted for reasons of poverty. She thinks about it for a while and asks: “Not even for being this poor?”

About this project

The unknown border of America

José Luis Sanz / Javier Lafuente

It has been ignored for decades. The strip of earth that connects Mexico with Central America is not as photogenic as a wall, nor does it have the myths that cinema and the American media have brought to the Río Bravo or the deserts of Arizona. It has been treated like just another Latin American border: disorderly, wild, porous and silent. But it is a dividing line that is crossed by more people ever day than anywhere else in the American continent, one of the busiest in the world. It’s an obligatory crossing point for the hundreds of thousands of Central Americans who are heading north. More than 120,000 migrants have been detained in Mexico every year for the last five years. It is estimated that 90% of the cocaine that will arrive in the United States has touched Central American soil at some point, before it is moved across the border with Mexico. It would be careless to talk about migration and drug trafficking in this region, without paying attention to this area.

The remoteness of the United States from this border aggravates the lack of interest for the area: a faraway border that can’t be counted in cities, but rather villages, hamlets and homesteads. The stories are not told in the voices of governors, but rather mayors, community leaders, soldiers, farmers and coyotes. To understand this border you have to lose yourself in the territory.

It’s a border characterized by difficult terrain, and is difficult to access along much of it. Some of its municipalities have their own languages and sometimes their own laws of silence. Many of the communities that have been forgotten – and assaulted – by the Guatemalan state – such as the Queqchís or the Cakchiqueles, take greater refuge in the innermost parts of this border. And other peoples, such as the Mennonites from Belize, found the perfect area to settle and build a life in these lands. In many parts, the “state” is a diffuse concept. Almost all the security policies of the successive Mexican governments in the last three decades have operated in this piece of earth, in which North America stretches out to become an isthmus. But neither the implementation nor the failure of these policies has merited more attention than a few short sentences. Until now, the southern border has lived and evolved far from the spotlights and far from uncomfortable questions.

The anti-migration maneuvers by Donald Trump have brought a new era of attention. The pressure he has been exerting in a bid to get Mexico to more aggressively control the flow of migrants, and his recent agreement to see Guatemala become the first recipient of deportees for the rest of the Central America region, led to the militarization of parts of the border. From the Central American side of the Suchiate River, Trump has found a comfortable silence: none of the three presidents from the northern Central American triangle – which accounts for more than 90% of the migrants who cross the border with Mexico – have publicly spoken out about the Mexican and US governments’ deal to build “the wall” for the north in this part of the south.

Also, the construction of the “Mayan train,” with which President Andrés Manuel López Obrador wants to connect Cancún with Palenque, passing by Tenosique, promises to transform the area. In both cases, it is unclear what kind of an impact the new policies will have, not just in terms of the ecology of the area, but also for the migratory, labor and criminal ecosystems in this part of the American continent. The southern border of Mexico is a great unknown, one that is rapidly mutating.

EL PAÍS and EL FARO have joined forces to try to explore this territory, and tell its stories. As part of the alliance that we began in April to explain Central America outside of its borders, over the next six months joint teams of journalists from both media outlets, more than 20 people in total, will work to divulge the identities, conflicts and questions that the area hides, narrating them in different parts and multiple formats.

It’s a risky strategy, not just due to the complex reality that we are trying to show but also due to the characteristics of the area, which is one of the most forgotten and violent zones on the planet.

We aim to delve into places that we think we know, such as Tapachula or Tecún Umán; at the same time as we penetrate more inhospitable and secluded parts such as Xcalak, Ixcan, Bethel and Laguna del Tigre. We will try to illustrate a mosaic formed by indigenous Mayans, Garifunas or Mennonite settlers; human flows that begin in Central America, Africa or Asia; by large swathes of legal and illegal crops; poverty, inequality, political powers and armed groups that are constantly changing; through countries that start to fall apart before your very eyes.

Chapter 3 of the Southern Border, coming soon.

Credits

- Project directors: Javier Lafuente, José Luis Sanz

- Coordination: Guiomar del Ser y Patricia R. Blanco

- Editing: Óscar Martínez, Jacobo García

- Design and infographics: Fernando Hernández

- Front-end: Nelly Natalí

- Texts: Jacobo García, Óscar Martínez, Roberto Valencia, Elena Reina, Carlos Martínez y Carlos Dada

- Video: Teresa de Miguel, Héctor Guerrero, Gladys Serrano, Mónica Gonzalez

- Photos: Héctor Guerrero, Fred Ramos, Mónica González, Víctor Peña, Gladys Serrano

- Photo editor: Héctor Guerrero

- Social networks: Anna Lagos

- Text editor: Ana Lorite

- Editing and video graphics: Sonia Sánchez Carrasco, Eduardo Ortíz

- Audio editing: Teresa de Miguel