The dark side of the Caribbean

The coastal area shared by Mexico, Guatemala and Belize is one of the most porous and little-known regions in the southern America border. Via three feature articles – in Xcalak, a remote Mexican village that lives off the cocaine that washes up from the sea; in Blue Creek, the powerful economic engine of the Mennonites; and in Puerto Barrios, the dark Guatemalan port in the Atlantic – this special report describes the enigmatic reality that exists just a stone’s throw from some of the biggest tourist attractions in the world

THE COCAINE THAT WASHES IN FROM THE SEA

The last man you come across in Mexico can be found at the following coordinates: 18º 12’ 9” N and 87º 50’ 36” W. He is almost always there working on his rooftop terrace. His name is Don Luis and his home faces the Caribbean Sea beyond the ubiquitous mangrove swamp. If you walk five minutes to the right, you are in a different country, but if you go left, you are in Xcalak in an hour – the first town within the Mexican border.

Don Luis is a muscular 58-year-old with dark hair and a moustache, and whose isolated dwelling is situated on one of oddest borders in the world. It is a line that divides a 99-kilometer strip of land into southeast Mexico and Belize, otherwise known as a key, which runs parallel to the Belize coastline. A military base marks the division between the countries. Mexico has 62 kilometers with barely a soul on them while Belize owns 37 kilometers crammed with tourists.

The last man in Mexico has no electricity or running water and no land access to his home either. There is no fridge or TV and his old cellphone only occasionally picks up the signal from Belize. But Don Luis knows a thing or two about survival, such as how to fish with a shoelace, desalinate water, sow seeds on the beach and use his mouth to suck the poison from the bite of a Nauyaca, one of the world’s deadliest snakes.

Luis Méndez was born in Mérida, Yucatan, and worked in a state government job until a friend suggested he become an estate warden. Three years after arriving in the furthest-flung corner of Mexico, he has learned that everything that comes from the sea has potential – a piece of rope can be used to jump-start a propeller, the sole of a shoe can be fashioned into a hinge and a can lid can be used to hold a nail in place.

Accompanied by Canelo, his coffee-colored Hungarian pointer, Don Luis gets up with the sun every day and takes a walk. Previously, he would walk along the beach, but now he strolls along a fetid bed of bladderwrack, a kind of kelp that is peculiar to the Caribbean and which gives off a smell like rotten egg, and dominates the coastline.

Strewn over the seaweed are old flip-flops and potato-chip bags and also hundreds of small plastic bags the size of the palm of a human hand. They are all the same and contain a mix of seawater and traces of white powder.

Don Luis could enjoy taking in the view of the second-biggest coral reef in the world, but instead he keeps his eyes to the ground. He says that he is simply checking that everything is in order, but during our walk together I hear him use a word I have never heard before: “playear” – literally, to beach. The verb refers to the never-ending search for bricks of cocaine that are dropped by small planes and may be missed by the speedboats that come to scoop them up. To not playear here is like not being Catholic in the Vatican.

“playear” (v): look for bricks of cocaine that have been thrown onto the coast from planes

Don Luis is a friendly sort who spends most of his life barefoot, only putting on shoes to walk along the beach. Another of his skills is recognizing different types of engine from the sound alone.

“The small planes make a grooooongggg noise,” he says. “But a boat with a 15-horsepower engine goes brrrrrrr, pause, brrrrrrrr, then another pause to get the bladderwrack out of the propeller. One with a 40 horsepower engine goes nyeeeeeee,” he adds, moving his fist from one side to another as though it were an accelerator. “And the 75-horsepower one…” He makes a similar sound to the last one, but lower and with an “o”. And on and on he goes, until he gets to the 100-horsepower engine, which is a veritable feat of vocal percussion.

Don Luis can also identify the different whistles that cut through the night air – those meaning “come,” “hurry” or “let’s go.” He can also tell who is whistling, matching the sound to the man’s nickname: el Gavilancito, la Zorra, el Pelón, el Guanaco...

The last man on Mexican soil might not have Netflix but from his own balcony he can watch speedboat races, police chases, and the comings and goings of the small clandestine planes. Yesterday, however, the flies threatened to curtail his enjoyment. “There were so many mosquitoes that we had to set fire to some coconuts to avoid having to go inside,” he says, recalling the scene the night before when he sat down with his wife, Norma, to enjoy the show.

The Caribbean, which contains thousands of islands that belong to a myriad of different countries, was described by the Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez as the only country that is made of water as opposed to land.

Less poetically, when Mexicans speak about the Caribbean, they mean the 1,176 kilometers between Don Luis’s home and Cape Catoche at the furthest point of Yucatan. This stretch of coastline includes areas such as Cancún, Carmen Beach, Cozumel and the Maya Riviera; in other words, the source of 35% of tourist income for this, the sixth-most-visited country in the world. The Caribbean here is the engine of an industry that accounts for almost 16% of Mexico’s GDP.

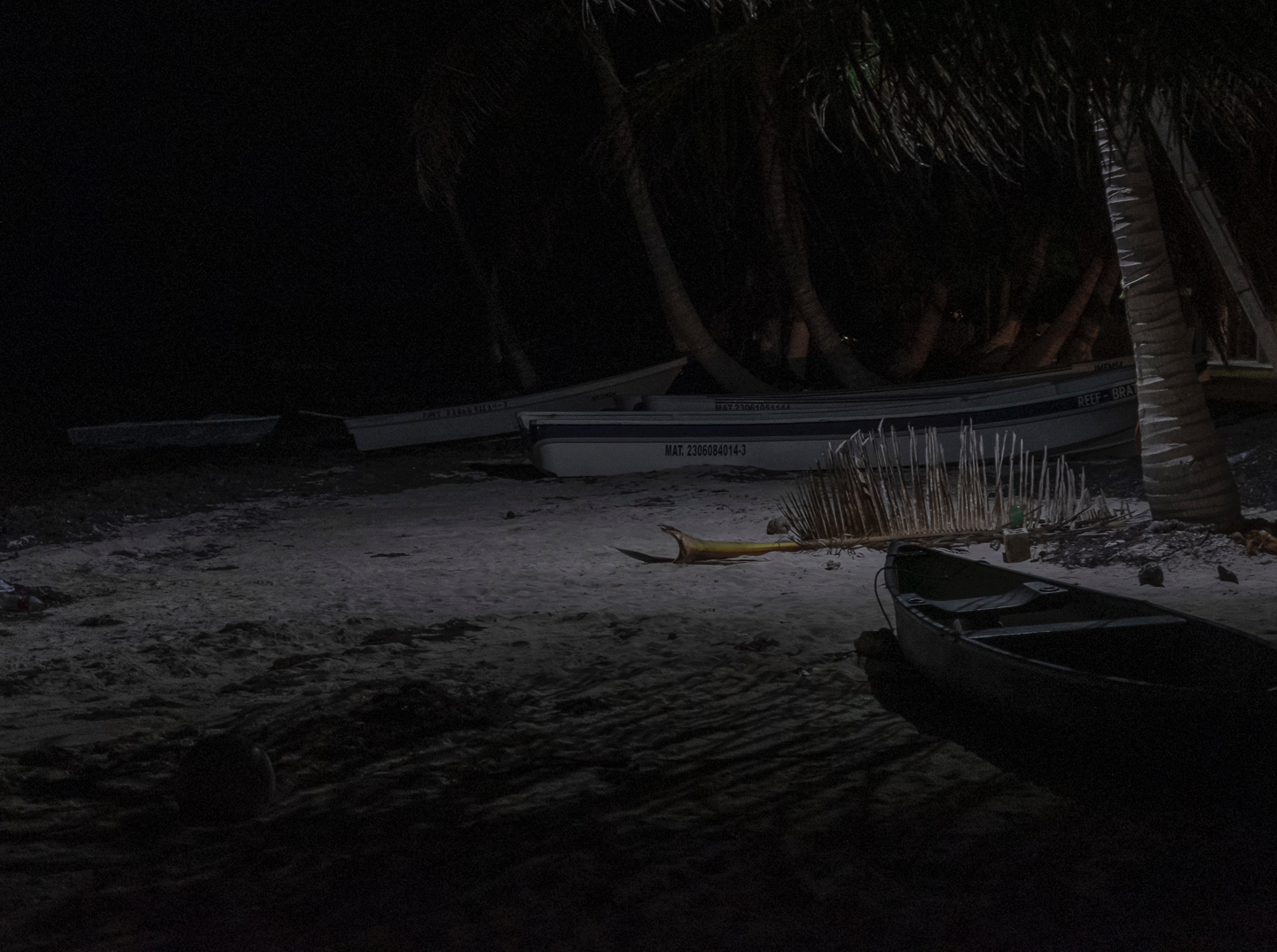

For the people of Xcalak, which is 412 kilometers away, the Caribbean and the trade winds that link them to it are also a source of income and a way of life. Located in the extreme south of Quintana Roo, two hours from Chetumal, Xcalak is a remote village of palm trees, turquoise waters, two lighthouses and a lake. There are three sandy streets that run parallel to the sea and another three that cut across them. If you had to picture paradise, you might be tempted to paint this community of 300 whose members are practically all related and refer to each other by nicknames.

But their beaches are also the final destination for anything of value that falls into the Atlantic; more often than not in the form of cocaine dropped by the small Colombian planes – an activity known here as “bombing.” The planes send the waiting launches the coordinates of where they are bombing and the speedboats promptly move in and fish the goods out of the water. But there is not always time to get everything. And even when they do, the cocaine bricks can end up thrown overboard if the speedboat has the police in hot pursuit. These packages often turn up days later wrapped in tape, either bobbing aimlessly in the water or snagged in the mangrove swamp.

Christopher Columbus would never have discovered America were it not for the trade winds – regular breezes peculiar to the Caribbean that sweep boats and other objects to the other side of the ocean. Thanks to these trade winds, wherever the cargo is dropped, sooner or later it will end up in Xcalak. For example, Don Luis has come across a Haitian doll, a bottle from the Dominican Republic and a piece of wood with African markings.

The direction of the trade winds

“In this town, playear is a profession that is passed on to the youngsters in the same way as fishing might be,” says Don Luis. “What else can you do if, after a life spent fishing or selling coconuts, your neighbor starts building himself a new house and turns up in a new car from one day to the next? Here, the youngsters are the first to learn that their futures don’t lie in working, but in searching and finding, and buying themselves a speedboat as soon as they can so that they can look some more. One day, marijuana might turn up, but a few years later it could be the cocaine that allows you to escape from poverty.”

At the end of February, Don Luis had to go to the city for a few days. When he returned, no one had to tell him a cargo had been dropped in his absence. “First I discovered that one person had hired a band, then that another had bought everyone in the town a beer and another had a new motorbike,” he says.

One of the traffickers that Don Luis watched run from the Belize police in front of his home yesterday is El Guanaco. Aged 33, he is a rough, dodgy-looking character who never stops smoking marijuana. As his nickname suggests, he was born in El Salvador and has had so many brushes with death it is a miracle he is still around. He says he left San Salvador to escape mobsters who wanted to kill him, fleeing to Belize where he worked on land belonging to Mennonites – the extremely conservative Christians who live on the border. He subsequently took refuge in Xcalak, the last place his enemies might think to look.

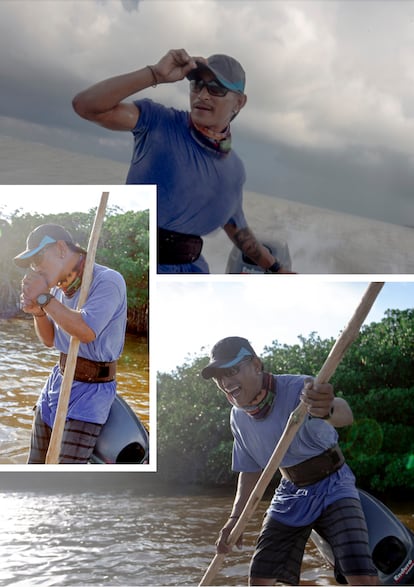

Dark-skinned, with a number of tattoos on his chest and back, El Guanaco is athletic. But today he is tired after spending the night catching lobsters. In Xcalak, lobster catching is closely regulated so he crosses into waters belonging to Belize where there are fewer patrols.

To catch the lobsters, he dives six feet down without oxygen and leaves the engine of his boat running in case he has to make a quick getaway. When he resurfaces, he spins around 360º with a flashlight, just in case the sharks arrive.

When he talks about last night’s “show,” it’s clear that what he likes most is to steal from under the noses of the people of Belize. “But you should know! They shoot with real bullets!” he explains, with a marijuana-induced giggle, in reference to the police from the neighboring country.

El Guanco might be tired, but as he lazily sticks his oar in the water he keeps his eyes trained on anything that floats in the water. “We have to paquetear, it’s the poor man’s lottery. You never know when the brick that will change your life will turn up.” “Paquetear,” the tireless search for drugs in the sea, and the second local verb that I note down in my pad.

“paquetear” (v): look for drugs in the sea

As he rows, not looking unlike a gondolier, El Guanaco casts his mind back five years to the moment he found a beautiful package of cocaine. “It was right there, in front of me,” he says pointing at a spot in the crystal-clear water. “There were three of us and we found 25 kilos, which we shared out between us. I got $50,000. I had never seen that much money before. I decorated my house with it and I bought myself a motorbike and another one for my wife... Normally, people go crazy and even throw the money up in the air, but I didn’t because I know what it is like to go without. In the end the money lasted less than a year.”

Together with the trade winds, the new ally of the pepenadores, as the collectors are known, is the bladderwrack, which leaves a dense blanket of vegetation on the shore that deters tourists, damages the corral and leaves the fish without oxygen. The algae spreads across the Caribbean, and is causing concern in Mexico, Panama, Dominican Republic and Florida. But not so for those who are taking advantage of sea currents.

“The movement of the banks of bladderwrack in the water reveals the direction of the current and helps us to know where the packages might turn up along the coast,” he says.

El Guanaco was given a beating a couple of weeks ago. Judging from the rawness of his knuckles, he tried to defend himself, but he clearly got a hiding. Ten people, including the mayor, kicked the living daylights out of him. Judging by the gaps in his story, you get the feeling he was trying to be a wise guy. He was working for one of the local drug lords, or at least, charging for scouring the sea for cocaine packages. But he left his boss and went to work for another one.

“Cocaine? Crack? Marijuana?” This is the sales pitch from the tattooed man selling me a six-pack of beer in a local store.

In a handful of the shops in the town, as well as beer, they sell “wet” cocaine – freshly plucked from the sea – at $5 for a bag the size of a fingernail. A similar amount of crack is considerably cheaper.

In Xcalak, local cuisine is not about red snapper recipes, it’s about how to cook the wet cocaine that arrives in the sea, a process a young local explains to me from his motorbike with a gallon of petrol balanced between his feet. “You put it all on the heat in a big pan and you cook it slowly,” he says. “You have to stir it all the time until the water evaporates but without burning it. Afterwards you put it on a board and you cut the cocaine with a big knife. You get the lumps out with a spoon.”

To make crack, the cocaine is cooked using a double boiler and mixed with bicarbonate of soda. A kilo of cocaine found at sea fetches $10,000.

According to the experts, Cancún, the Maya Riviera and the coast of Quintana Roo are controlled by the Sinaloa, Golfo and Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG) cartels. The Zetas, a cartel that once terrorized people all over the country, have lost power, but still hold on to small cells in tourist areas. In the rest of the region, small outfits, almost families, are also involved in the business.

The drugs found in Xcalak are taken to Chetumal and are then sent north or to Cancún, which, according to the National Addiction Survey, has the third-highest consumption of cocaine in the country. In the other direction, a well-maintained highway leads from the capital of Quintana Roo to Veracruz and Brownsville, and in just 24 hours a kilo of cocaine soars from $10,000 to $60,000, the figure it fetches in Texas.

The remains of two wrecks poke out of the water in front of the docks. Many ships fitted with keels get wrecked on the corral reef coming in to Xcalak. There is only one way in and that is by lining up with the two lighthouses and keeping the dock on the portside.

On the streets of Xcalak, there is evidence of a more prosperous era; a period when there were 3,000 inhabitants instead of 300, a shipyard and even a dance hall. Back then, there were huge quantities of sea snails, tortoise eggs, lobster and shark to export on the docks. It was a time when Xcalak was “bigger than Chetumal,” according to 75-year-old Melchor, who, with birth certificate “Number 2,” is the oldest person in town. That lasted until 1955 when Hurricane Janet leveled everything in its path and killed a third of the population. “At that time, there were a lot of people unloading at the dock,” Melchor says. Pointing to an empty street, he adds: “There was even an ice factory and a cinema.”

Since then, the town has been surviving on tourists, fishing and “bricks,” says El Guanaco with a hint of sarcasm. The visitors come for fly-fishing or diving and they stay in the six hotels that have rooms for $120 a night and provide work for 40 locals. “But fishing is increasingly less reliable and the tourists don’t get as far as here, so then you have to wait to get lucky – see what the sea sends your way,” he says.

According to the lighthouse keeper, José Miguel Martín, 55, the main activity in the town has always been coconuts, sea snails and lobster. “But there are long periods when the season is closed and then, when it became a Natural Reserve in 2000, there were even fewer opportunities,” he says.

From the top of the lighthouse, just meters from the Navy barracks, you get a clear view of the teenagers on their motorbikes, laden with tanks of petrol and moving in the direction of the track that runs parallel to the sea and takes them to the camps where they spend hours hanging around and cooking. “How can I tell my son not to go when all of his friends are involved in this?” he says with a shrug.

José Miguel Martín, the National Commission of Protected Areas (Conanp) and a navy base with 10 marines are the only State presence in Xcalak. Curiously, the locals hate Conanp more than the navy personnel. This is because its four delegates are constantly devising strategies to make sure the locals refrain from fishing during the closed season to protect the corral reef. As the town has no local police force, any irregular activity is reported to the navy base. In Xcalak, it’s riskier to fish during the closed season than to sell on a kilo of cocaine.

According to the Mexican Navy, a small aircraft can be seen coming from Colombia or Venezuela and crossing Quinatana Roo airspace every couple of days. The general of the Chetumal military zone, Miguel Ángel Huerta Ceballos who is in charge of monitoring activity along the Caribbean coastline, says that in the first five months of this year, at least 100 drug cartel-operated flights have been spotted.

“Are the parties in the town big?” I ask Joaquín aka “El 75,” whose main influences are MTV and cable TV – the most efficient services in a town without running water.

“Do you know Ibiza?” he replies. As far as this 24-year-old is concerned, the best party in the world is when they celebrate the approach of Easter by getting wasted for three days and firing shots into the air. Then there are the parties when one of the locals finds a brick.

Joaquín has been nicknamed El 75 because he is bigheaded and has legs like a 75-horsepower engine. He tries to behave like a gentleman during his outings with tourists when he fills the small icebox on his boat with water and soft drinks, loads up with masks and flippers and points out the stingrays and the Manatees while allowing his clients to arrange the canopy to their liking. But when there are no tourists, El 75 gets together with his friends and searches in “el recale” – the third local expression I note down.

“recale” (s): an accumulation of algae on the shore

He says that some years ago his uncle ruined his life after finding one. “Because he doesn’t know how to read or write and he was tricked and given just 70,000 pesos [$3,650]. And he lost his head and spent it all on alcohol and bullshit that was even worse,” he says.

El 75 works a GPS with ease. He also knows his way around an engine, but what really embarrasses him is that he does not know how to use cutlery. With a touching innocence, he says that one of the most humiliating episodes of his life was when his relatives realized that he did not know how to hold a fork or use a knife to cut his meat during a family occasion. So now he is practicing, he says. When it comes to recognizing which cartel the cocaine belongs to, he has no such problem – “It depends if it carries a skull or a scorpion,” he explains.

The cemetery of Xcalak is on the edge of the town, a sandy spot salvaged from the swamp. Every day when the sun goes down, Doña Silvia arrives with a machete and a broom and cleans the place up because two of her children are buried here. In this forgotten paradise, crack costs the same as a can of Coke and a bag of fries. That has consequences, generally ones that can be found in the cemetery. According to the official data, Guatemala has one suicide for every 41,666 people but in this town of 300 and less than 100 graves, there are at least four – all of them young people.

“This grave belongs to a boy of 22 who hung himself; and this one to a boy of 23 who also strung himself up; and there, to a 25-year-old who threw himself off a tower, and this one…” says the woman as she walks among the headstones in one of the saddest cemeteries in the world.

I am trying for an interview with the Xcalak representative, a role similar to that of mayor but with fewer responsibilities. At least a dozen people have suggested that he and the Mayor of Mahahual are the drug lords around here. Allegedly, they are the ones that are doing the buying, providing the equipment and paying for the camps and the merchandise. The representative tells me he has to leave town on business but that I can speak to his deputy, who lives on the edge of town.

In the shade of the bougainvillea and the coconut trees, two families finish eating. They laugh and joke and use toothpicks to fish out the food that has stuck in their teeth. One of these is the family of the deputy, Enrique Esteban Valencia, and the other is the family of the mayor of Mahahual, Obed Durán Gómez.

On the checked tablecloth are the remains of a meal of lobster and shrimp. Four local police are guarding the scene with their guns hanging from their necks. They are not allowed to sit or join the meal but they chat away to the most powerful men in the area and are obviously at ease in their company.

What do you suggest for the bladderwrack, I ask the deputy. Do you want the government to send people to clean it up, as the hotel owners are hoping?

“They shouldn’t come, that is not the answer, no, we don’t need anyone coming here,” says the deputy, who is clearly against the idea of large numbers of outsiders on the town’s beaches.

How do you deal with the drug-trafficking problem and the fact that the town’s young people are involved in this activity?

“I wouldn’t call it activity. People are free to go where they like. It’s nothing to do with us; there are specific authorities for that.”

But it is obvious that many people are involved in scouring the beaches and your town is an important entry point for drugs.

“I don’t know what you are talking about. It’s not something we are in charge of,” says the mayor, and the deputy agrees.

“What about the camps we have seen?” I persist

“I don’t know where you are getting your information from, but those are not camps,” says the mayor. “People need land to live and if they don’t have land they have to be given it.”

Many people have linked them to the sale of the goods found in the sea.

“They can say what they like, call me a drug trafficker or whatever, but what is happening is that we are doing things and that irks people,” says the deputy.

What things?

“Fighting for our rights, to put an end to our abandonment and also fighting against crime.”

Do you want more police? Do you want the National Guard here?

“Look, we keep things under control in our own way,” says Obed Durán, who was the head of the Mahahual police until he made the switch to mayor four months ago. “And there are three ways to sort things out [if someone makes trouble]. First, we give them a chance and take them to a rehabilitation center without beating them or anything. If they make trouble again, they get a warning and if it happens a third time, well, a bag of lime avoids unnecessary expense.” And he lets out a bark of laughter so loud that the deputy joins in and bangs the table.

“What do they aim to do with the bladderwrack, I ask?” Do they want the government to send people to clean it up, as the hotel owners are hoping?

“They shouldn’t come, that is not the answer, no, we don’t need anyone coming here,” says the deputy, who is clearly against the idea of large numbers of outsiders on the town’s beaches.

“How do you deal with the drug-trafficking problem and the fact that the town’s young people are involved in this activity?” I ask next.

“I wouldn’t call it activity,” he says. “People are free to go where they like. It’s nothing to do with us; there are specific authorities for that.”

“But it is obvious that many people are involved in scouring the beaches and your town is an important entry point for drugs,” I say.

“I don’t know what you are talking about. It’s not something we are in charge of,” says the mayor, and the deputy agrees.

“What about the camps we have seen?” I persist

“I don’t know where you are getting your information from, but those are not camps,” says the mayor. “People need land to live and if they don’t have land they have to be given it.”

“Many people have linked them to the sale of the goods found in the sea,” I say.

“They can say what they like, call me a drug trafficker or whatever, but what is happening is that we are doing things and that irks people,” says the deputy.

“What things?” I ask.

“Fighting for our rights, to put an end to our abandonment and also fighting against crime.”

“Do you want more police? Do you want the National Guard here?” I ask.

“Look, we keep things under control in our own way,” says the mayor, who was the head of the Mahahual police until he made the switch to mayor four months ago. “And there are three ways to sort things out [if someone makes trouble]. First, we give them a chance and take them to a rehabilitation center without beating them or anything. If they make trouble again, they get a warning and if it happens a third time, well, a bag of lime avoids unnecessary expense.” And he lets out a bark of laughter so loud that the deputy joins and hits the table.

Evening falls in Xcalak and a light breeze moves the palm trees and the boats. The translation of the original Latin alisio describes “a soft and warm wind,” something that the English later dubbed as trade winds. The ease with which Xcalak has to create new words has also, in this case, managed to refine that term, merging the two different definitions.

THE FOURTH NATION

The official from the National Institute of Immigration (INM) leaves the office wearing half the reglementary uniform: olive-green pants and a white singlet top. The officer looks up and down, scratches his testicles, rubs his few-days-old beard, speckled with grey hairs, and goes back to his testicles. He is surprised to see someone who is not a Mennonite, black or a resident of La Unión.

The migration office in La Unión, in Quintana Roo, appears in the INM database as a two-story building with air conditioning and a public reception area. But in reality the office, located 1,396 kilometers from the capital, is a mix of a house, garage, office and henhouse, where the most advanced technology is a notebook, ventilator and the hand scratching the testicles, which is now holding a pen.

“Are you going to go to Belize? But there’s nothing there,” he says, answering his own question.

What the officer calls “nothing” is a country of 370,000 people who speak English and creole and recognize the United Kingdom’s Queen Elizabeth II as the head of state. It is also where, right now, a funeral is being held for Henry, a young guy who was killed by two machete blows to the head, and was known to his Menonite friends as “El Happy.”

“On the other side, there is no one to stamp your entrance into Belize,” the official says. “So if you are not going far, just cross over.”

In the time it takes for us to talk, four women carrying cleaning products and a young guy in a Barcelona soccer shirt holding two boxes of beer have crossed from this hot, lush place, filled with flies, in Mexico into Belize, without documents, and without anyone raising even an eyebrow. In the other direction, crossing in from Belize to Mexico, is a family of Mennonites and a young Mennonite woman with her black driver. At 6pm, driving into the capital, across the border shared by Mexico, Belize and Guatemala, the immigration process is handled by a “you look familiar” strategy.

La Unión is Quintana Roo’s last important village – important in that is has a grocery store, church, public office (the INM) and a navy base, a spot known as the “white trail” for being one of the most popular spots to bring in cocaine from the Caribbean to the United States in the region.

On the Mexican side, a highway runs parallel to the Hondo river, where more than 30 communities are spread out across 100 kilometers and the natural border does not accept passports. Every day, hundreds of families cross back and forth the river to go to school, visit family, fall in love or buy cheaper products, long before this was called smuggling.

In Cocoyol, one of the riverside communities that harvests corn and cane sugar, I meet Carmen Martínez, 48, and José Jones, 47, as they get out of a wooden canoe that they have rowed from Belize, which is just a stone’s throw away.

The couple is the perfect embodiment of mestizaje, the mixing of different races. José is from Belize. He has tanned skin, a strong and muscular physique, and works as a yerbatero, a person who uses plants and roots to cure conditions such as pneumonia, rheumatism and reptile bites. Carmen is from Mexico. She is slight, with large eyes and sells second-hand clothes on both sides of the border. They met when José crossed over to play a soccer game. They liked one another, got married and went to live in Belize because the salaries are better. But they return to Mexico every day to eat with the family.

“My daughter went to an English school on the other side [Belize] and now works in a hotel in Cancún [in Mexico],” says Carmen, who feels lucky to have raised a daughter in a bilingual world.

“No one controls the crossing” but sometimes it is more difficult in the Marine base, when “you bring a living animal, like a pig for Christmas, so it’s better to warn the soldiers ahead of time,” she explains, a few meters from the military base.

When asked about what they like in each country, Carmen criticizes the brutality the Belizean police have become sadly famous for. “In Mexico, there is more respect for human rights. Even with the corruption and bribes, there is a protocol, but in Belize, they don’t care and the officers extort you and take away your money in front of everyone,” she says.

Cocoyol is one of the infinite spots where you can cross the border without going through security control. But if you want “action” go to San Francisco Botes, suggests a young man, who describes it as the “Tijuana of Hondo River.”

Surrounded by lush greenery, on the border of the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, San Francisco de Botes is home to just 400 people and has nothing in common with the famous capital of Baja California. However, he is right in describing it as the main uncontrolled crossing for goods, animals and people. When I arrive at the jetty at 9am, it’s like someone has suddenly turned off the music. Everyone stops what they are doing: the young man unloading boxes whistles at the sky, the boatman looks at the floor and the woman who was taking goods off a pickup gets back in the car and closes the door to avoid uncomfortable questions.

Watching, listening and staying quiet is the best strategy in an area where, in the last year, a dozen planes carrying drugs have crashed among the wetlands, according to the local press. This remote area is filled with the nighttime buzz of Cessna, Rockwell and Jet planes flying overhead with their lights turned off, and landing to be met with an efficient network of collaborators who provide fuel next to the secret runways. When marines found the last plane in March, just a few kilometers from here, they also discovered two trucks with a thousand liters of jet fuel among the vegetation. The most recent and shameless case took place in December, when a small plane landed at 3.30am at the international airport in Chetumal. When security at the airport responded, the two pilots had already escaped, jumping the fence and leaving the Jet Hawker on the runway with 15 passengers and 1.5 tons of cocaine on board.

“Of course you hear the planes every day,” the officer from La Unión –who preferred not to give his name out of fear that his superiors would punish him – tells me as he leans against the door. “On this side of the border, everything passes and nobody does anything. But don’t believe that the main stuff comes in on planes,” he says. “Right there, vehicles come and go at will,” he says, pointing with his chin to a dry point in the river in front of him, just 50 meters from the military barracks.

For the customs official, fed up with the institution and with life, the surge in criminal activity is connected to the new Mexican president, Andrés Manuel López Obador. Since he took office in December 2018, the president has set his sights on the INM, which his secretary Alejandro Encinas, described “as the most corrupt organization in Mexico,” which is a bit like getting distinctions in French in France’s Sorbonne University. Since then, López Obrador has removed 67 officers from the office in Chetumal, and in other places such as Tapachula (Chiapas) the purge has been so sweeping that the government directly decided to close the immigration office entirely, leaving hundreds of migrants in limbo.

“They have humiliated and offended us. They have removed many colleagues without any explanation and this is not fair,” he complains. The official misses the heavy-handed approach of the old days, when there were “surprise operations” and raids to arrest Central American migrants. Although the figures show that those times are back – there were more migrant deportations in the months of April and May of this year, than in the same period last year under former president Enrique Peña Nieto – the officer blames the lack of border control on López Obrador’s “open-door” policy and the arrival of migrant caravans that, according to him, “spread viruses and diseases in the communities they travel through.”

On the other side of the river in Belize, two large, black officers with no shirts smile as they watch a TV show in the customs office in Blue Creek. It is a small, prefabricated house with a table, television and an armchair that is breaking at the seams. This is where one of the giant officers sits as he watches the episode, his gun and the remote control lying on the armrest.

“If you are only going to be in the Mennonites area, let’s go, let’s go,” yells one, mixing Spanish and English and waving his hand in the air. Without taking his eyes off the screen, the officer opens the door to a new world, and one of the most contrasting images of the border.

On one side, there is La Unión. The last town of Mexico is chaotic, Catholic, rural, and a bit dirty. The people there grow sugar cane and drink beer like it is water. On the other side, there is Blue Creek, the first town of Belize is conservative, efficient, high-tech, Protestant. The people there speak Old High German and it’s impossible to get a drop of alcohol. It’s an unnerving place that should have been different.

Spread out across countries such as Canada, Mexico, Paraguay and Bolivia, the Mennonites are a Protestant sect that emerged in the 16th century, and have more than a million followers in Latin America. It is a peaceful group that sprung up in what is today Switzerland, Germany and Poland, who were persecuted and forced to emigrate to countries such as France, Russia and Canada after breaking with the Catholic Church and the Lutheran Reformation in 1536.

Blue Creek is not a village as such, it is a community of 800 Mennonite families who live in US-style houses, with a porch and gable roof, scattered across perfectly arranged crop fields that are connected by paved and well-lit roads. In Blue Creek, which is only 20 kilometers from one point to the other, nobody is walking around; there is not one piece of trash on the ground, not a single drunk person and no public square, Town Hall or bar. As far as the eye can see, there is nothing but poultry slaughterhouses and fields of rice, beans, African palm and mahogany. In the village’s only shop, which also acts as a bank and civil center, everyone – mainly freckled, almost transparent-white Mennonites – and the odd Salvadoran worker, greets each other as they pass.

Blue Creek is the twin town of two other Mennonite communities, Shipyard and Spanish Lookout, which are home to around 3,000 families. Both of these ultraconservative communities refuse to use electricity and travel in horse buggies.

Few borders in the world give way to such a big visual contrast as the border that divides the United States and Mexico. In places such as Ciudad Juárez and El Paso, or Tijuana and San Diego, the tin-sheet houses face golf courses and neatly arranged housing developments. This image is repeated at the border between La Unión and Blue Creek, 3,600 kilometers away, where one of the most languishing places in Mexico looks out onto one of the world’s most efficient. In this remote corner, Mexican workers flee to the rice fields when they see us, thinking we are the Belizean police coming to arrest them and not journalists from EL PAÍS and El Faro.

MENNONITES, THE WHITE SPOT ON THE BORDER

The Mennonites arrived empty-handed in Belize almost 60 years ago from Chihuahua in Mexico. The government of Belize, which at that point was still called British Honduras, gave them more than 85,000 acres (nearly 35,000 hectares) in the northern tip of the country, a mountainous area covered with kapok, mango and mahogany trees, of which not a leaf remains.

In exchange for land and autonomy, they began working like crazy and today are the engine that drives the country’s food sector. Mennonites produce 95% of the chicken that is eaten in Belize, and 80% of corn, rice, beans and sorghum. They live in a separate world, operating with religious, tax and educational independence, where children receive classes in medieval German. They also have their own health and police system, as well as a road network and even a small hydraulic plant.

But the power won by a handful of families, who appear to have just stepped off the boat from Central Europe, is viewed with suspicion by the Belizean governing class, which is not used to economic surprises that aren’t from Great Britain. “We are aware that we cause suspicion and envy and that they want to take away our independence,” says Rubén Fonseca, the mayor of Blue Creek. Drug trafficking is a good argument to do this.

For the small planes that enter the Caribbean, the perfectly designed fields are the ideal place to land and stock up and, since January 2019, at least one burned-out plane has appeared every month in Blue Creek, says Fonseca.

As well as mayor, Rubén Fonseca is a shareholder in the powerful Caribbean Chicken company, which produces a third of all chickens eaten in the country. But he arrives at the interview with his hands dirty from the slaughterhouse, a checkered shirt stained with oil and in work boots. He belongs to the group of modern Mennonites – those who use cell phones, cars and download apps – and is the father of three blonde children who look like they are straight out of a perfume ad.

Fonseca admits that several Mennonites have been arrested for drug trafficking and that the issue is damaging the reputation of the community. “But this is beyond us and even the governments of the countries. When we hear a plane crash, we don’t do anything. We let everything burn and don’t get involved,” he says in an exotic language that mixes Hollywood English, the Spanish of farmers and German from the time of Menno Simons, the founder of the Mennonite community who died in 1561.

“In the 1970s and 80s, it was crazy,” he remembers, thinking of the years the Mexican drug trafficker Amado Carrillo Fuentes, nicknamed the “Lord of the Skies,” and Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar discovered that small planes were the best way to transport a ton of cocaine to Mexico or the United States, flying low and without lights so as to not be detected by radar. “That stopped in the 1990s, but right now this area has become active again,” says Fonseca, pointing to the perfect two-kilometer road that divides the barley fields like a knife in butter. “Up to two planes have been seen refueling in just one day,” he explains.

Fonseca admits that it’s the perfect place for an operation that is done in just minutes: the pilot sends the coordinates, a crew lights up the runway with canisters and rags drenched in gasoline, the plane lands, unloads and in no time the goods are on the Mexican side of the border on their way to Escárcega and the Gulf of Mexico, one of the main transit points for drugs and migrants.

Abraham Rempel is dressed in jeans and a worn-out shirt, despite being one of the most successful members of the community. He is a pilot and the owner of one of the businesses that fumigates Mennonite fields. Rempel recognizes that it is tempting to work for drug traffickers and knows of many pilots who were trained by him who have never been heard from again. Rempel explains that two types of planes arrive in Blue Creek: “The King Air planes, which cover short runs and land on runways that are less than a kilometer long, and the Jet planes, with greater speed but less autonomy, that need long runways that are only found here,” he says in shaky Spanish.

“Happy wouldn’t have liked this,” says one of his best friends at his funeral. The nickname of 34-year-old Henry is far from appropriate given he is covered in a burial shroud in a box. If he were to wake up now and take a look around, he would see an old woman shooing flies away from his face with a duster, four other old women crying, and a hundred men dressed in black repeating a funeral prayer from the 16th century. Thanks to the old women’s efforts, the two machete blows to the head can’t be seen.

In 1966, the Mennonite communities from the north of Belize split between Blue Creek and Shipyard. They are physically neighbors but socially very different. The first, made up of 800 families, has embraced modernity, new technology and field industrialization. The second, made up of 3,000 families, has chosen to follow the orthodox line and has not even allowed the electricity company to bring power to the village.

In Shipyard, they use steel wheels, candles for lighting, wood for cooking and animals for working the field. Music is banned. It goes without saying that in the most boring place in the world, there is no cinema, library or even a park, and the main “crime” committed by young people is using a cellphone in secret. El Happy had fled all this years ago when he met people who played the guitar and listened to the radio, his friend remembers as she stands in front of his coffin.

Getting to the funeral is like traveling back in time; it is the perfect landscape for a period film. Dozens of horse-drawn carriages wait at the entrance. A large group of white, blond children, with neatly combed hair and overalls, waits outside. They don’t yell or play or run or pull each other’s hair like the rest of the kids. They are dressed in short-sleeved tops that have extra sleeves sewn on to them so that today they cover the entire arm. The women have headwear and wear long, black, felt-wool dresses and stockings, even though it’s 40°C.

No one wants to explain what happened to El Happy. The only thing that’s known is that he received two machete blows to the head and was later dumped in an irrigation canal. As to whether he was mixed up in drug problems, if it happened on a bender or from poor judgement, nobody wants to talk about that, investigate or even know.

Inside, the men, dressed in suspenders and shirts buttoned up to the neck, with cheeks red from the sun and the big hands of farmers, recite passages from Gesangbuch, the book of prayers, next to the body. A funereal din that has been going on for six hours, without a change in rhythm or timing. The Mennonite silence imposes its law on the community. Its survival depends on it.

FEAR ON THE MAINLAND

The taxi driver steers the old Toyota through Puerto Barrios with his arms stiff as baseball bats, his eyes staring unwaveringly at the rear-view mirror.

“Look, I’m just not up for any kind of shit,” he mutters again in the general direction of the passenger.

The car door doesn’t shut properly, the windshield is cracked in two places and held together with duct tape, and a bunch of cables are protruding from the hole where the radio should be. Adrián nevertheless demands that I shut the door gently, pay in small change and make sure I do not damage the upholstery on a vehicle that seems like it came straight out of war-torn Aleppo.

The driver is sweating profusely, and only takes his eyes off the mirror to wipe his face with his shirt sleeve. His only friendly gesture is for another taxi driver who passes by, and who is greeted with a honk and a wave of the hand. The famed Caribbean friendliness never made it into the inside of this taxicab, and the man gets just a little angrier over what he considers to be an absurd route. And the fact of the matter is, it is.

The two men who have just exchanged greetings both participated in a mass beating three months ago. Just a few streets from here, two criminals were stoned and kicked to death. It was February 18, 2019 and both taxi drivers were part of a crowd of between 500 and 700 people who cheered as though it were some kind of show.

The grand finale came at close to 9pm, when, after having been kicked in every possible way, an 18-year-old named Oliver González was doused in gasoline and someone dropped a lit match on him. When there was nothing left of him but a blackened trunk twitching on the pavement, the crowd gathered around and spit on him, yelling out: “Thief!” Standing further back, the least-violent observers shouted out: “Yes we can!” as they filmed the whole thing on their cellphones.

Meanwhile, the taxi drivers were part of another nearby crowd that was dealing with 19-year-old Víctor Reyes. Reyes was dragged by the hair, then had his stomach trampled. After that, people hit him with a traffic sign and a brick. For the last half hour that he clung on to life, the mob kicked his head like it was a football. The fact that the young man’s father arrived on the scene did not stop the 500 or so taxi drivers, local residents and various passers-by who had decided to join in. When the old man pulled out a machete and stood between his son and the bloodthirsty mob, the young man was nothing more than a bloody pulp writhing on the ground in agony. The father’s courage only lasted until someone screamed: “Burn the old man, too!”

Six months ago, a violent gang named Barrio 18 arrived in town and began asking taxi drivers for weekly payments, explains the chief of police down at the precinct. One by one, taxi union leaders received warnings, always in the same manner: an individual on a motorcycle would pull up to the taxi driver’s window, throw him a cheap cellphone, and utter one sentence: “Take it, they’re going to talk to you soon.”

After resisting for three months, finally the town’s thousand taxi drivers agreed to make an initial payment of 150,000 quetzales ($20,000), representing 150 quetzales ($20) per taxicab per week. But the taxi drivers had set up a trap to catch the extortionists, who were handed over to the police.

But those who wanted more, who wanted revenge instead of justice, began to flood the taxi radio channel and the WhatsApp groups with messages to the effect that the gang members were going to be released for lack of evidence. At that point, people began milling in front of the metal fence at the police station. Things heated up, until finally the miscreants in custody were dragged out by the hair and delivered to the lynch mob.

Three months after the lynching, a tropical calm seems to have descended on this place again. At times, it feels as though the vehicle itself had slipped into a deep repose. But that is only until 8.45pm, when the gruff driver suddenly steps on the brakes and explodes:

“Look, friend, I don’t go down those streets any more. And another thing: I can’t take you around any longer either. This is the end of the line.”

Because...?

“Because of the time,” he says, ending the conversation.

After the lynching, the gang’s response was to embark on a cabbie hunt. In a Facebook message signed by El Barrio 18, the gang threatened to “kill those son-of-a-bitch taxi drivers one by one,” and announced a 7pm curfew, after which they threatened to kill any cabbie found on the streets.

It wasn’t long before the threats became a reality. Just a few days later, the motorcycles stopped delivering cellphones and began delivering bullets to the head instead. There has been an average of one attack every 15 days, resulting in four dead taxi drivers and two more barely holding on to life. The gang now wants the taxi leaders’ heads on a platter. When one of them refused to be interviewed for this article, he was crying. This hulking giant of a man had spent the last three months inside his house. “The gang wants to kill me, the police want to arrest me, and I can’t even work for a living anymore,” he sobbed.

Before stepping on the gas and taking his leave with a grunt, Adrián – who asked not to use his real name – mops up his sweaty face again. For the last two hours he’s been scanning every motorcycle that shows up in the rearview mirror. At this point, the passenger is sweating, too. The Finns have 40 different words for snow, and painters can differentiate between 105 types of red. In the most stifling city in Guatemala, heat comes in many different tones as well.

Puerto Barrios, located on the Caribbean coast of Guatemala, between Belize and Honduras, is the biggest city in Izabal department. Located a five-hour drive from the capital, it is a dusty, hostile town of around 260,000 residents, and in recent years it has unfailingly been included on the list of Guatemala’s 10 most violent cities. It is also the administrative seat for places such as Morales, El Estor and Livingston, where the seafaring mystique was long ago replaced by more mundane elements such as cargo truck deliveries, drug trafficking and corruption. A mission of explorers sent here by the government in 1902 described it as a place with “a sickening climate,” with temperatures of up to 40ºC and humidity levels of 90%.

Puerto Barrios is a flat, dispersed city where the streets lead to the sea. The market is at the heart of this stain on the landscape built with half-finished houses where metal rods stick out, crowned by soft drink bottles. In Puerto Barrios, there is not a single building over three stories high, not one single escalator, and the only recreational areas are the Pollo Campero fried chicken restaurants and the tiny wharf where children play in the shade of containers belonging to Chikita, the banana multinational. Life here revolves around two ports: the public one, Santo Tomás Castilla, and the private one built by the United Fruit Company, which provides around 5,000 direct jobs. The main streets are clogged with trucks taking out bananas, African palm and nickel 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and bringing in plastics from Colombia and wrecked vehicles from the US for resale.

Puerto Barrios could have been a paradise destination surrounded by jungle, bays, islets with white sandy beaches and crystal-clear waters. But more than half the streets here are unpaved, and both the water and electricity supplies come and go as the waves of the sea. In this gateway to the Caribbean, it is easier to die under the wheels of a 16-ton truck than from a coconut dropping on one’s head.

Barrios is the ugly tip of Guatemala’s only outlet to the Atlantic, a 148-kilometer stretch of coast between Honduras and Belize, six hours from the Mexican border, and a key location in the traffic between Central America and the Caribbean islands.

Adding to the importance of the port is a coastal topography with as many spikes as the encephalogram of a madman. Endless routes leading in and out, concealed by a lush growth of palms, mahogany and ceiba trees, make this a mandatory stop for the light aircraft and speedboats that cover the revitalized cocaine route linking Mexico to the Caribbean through Río Dulce and the Petén department.

In the mid-1980s, more than 75% of all cocaine seized on its way to the US was intercepted in the Caribbean. Yet the region had already become less relevant after the Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar decided to use Key Norman in the Bahamas as a refueling spot for drug planes headed for the US. The volume of drugs passing through the Caribbean fell 10% in 2010, according to the US Drug Enforcement Administration.

But the US State Department feels that the route is currently experiencing a revival. In recent years, the flow of drugs has grown fourfold thanks to new leading roles by Dominican Republic and Venezuela. The US figures that nearly 80% of the cocaine it consumes goes through Guatemala, and that the Central American country seizes barely 0.5 % of these shipments, according to official figures provided by President Jimmy Morales, who nevertheless talks about “record” drug seizures since he took office in 2016.

That same year, the notorious drug trafficker Marllory Chacón told a Florida court that her former associates, the Lorenzanas – a family clan that has traditionally controlled the drug trade in Guatemala – received at least five shipments of cocaine of between one and two tons at their property in Puerto Barrios. The drug arrived on speedboats from Colombia after making a refueling stop in Panama. Thanks to that confession, Chacón, who had been sentenced to 12 years in a US prison, was released in March.

Puerto Barrios is also one of those easy places that criminal groups in the US choose to introduce weapons into Central America, the most violent region in the world. In 2016 and 2017, the tax agency SAT reported seizing more than 10 containers shipped from the US and Panama containing rifles, small arms and ammunition, making Izabal the second department with the highest seizure figures after the capital, according to SAT.

Moving in the opposite direction, Puerto Barrios is a major departure point for thousands of exotic animals, whose sale represents the third-most-lucrative illegal trade after weapons and drugs. A scarlet macaw from Belize or Guatemala, two of the countries with the world’s greatest biodiversity, can fetch $3,000 on the black market through online agreements between the seller and the buyer, according to the Wild Conservation Society (WCS).

“The geography here is a bitch, and these waters are almost always calm. They’re ideal for nighttime activities,” says the police officer who is taking me on a night patrol on condition of anonymity. Then he points at the Bay of Manabique. “Just in this area ahead of us, we’ve tallied up to 98 easy access points for unloading. And yes, they’ve bought more surveillance equipment, but not one boat, not one motorcycle.”

This policeman from Puerto Barrios is a mid-ranking officer with 15 years of service. We drive down one of the streets in the neighborhood of El Estrecho, where the police enter gingerly, not because this is an especially violent place, but because they don’t have the motorcycles to deal with the muddy terrain. Homes here are built right on the seafront, the streets are unpaved, and there are no basic services. Families spend their time sitting on chairs outside their door. In a tone that combines resignation and pride, the officer notes that Puerto Barrios “doesn’t give a damn what happens in the capital, because people here are geared toward the Caribbean countries that it shares borders with.”

“Is it true that the gangs have arrived in town, as the official version claims?” I ask, alluding to Barrio 18.

“Nah,” he replies. “Most of them are the same old gangs who keep changing their name.”

Just a few kilometers from Puerto Barrios, in the municipalities of Río Dulce and Livingston, hundreds of young backpackers from all over the world laugh, drink and fill the restaurants geared to tourists. But Puerto Barrios has been left out of this privileged route, and it spits on visitors. Very few people have any desire to stay in a place with a daily traffic of a thousand cargo trucks, and where the only decent hotel dates back to Tarzan’s glory days. So the bravest among the tourists come as far as the pier, then hightail it back toward the other end of the bay.

The ships’ crews, made up of Filipinos, Liberians and Chinese sailors, don’t even get off their vessels for fear of getting mugged. The magic of the waterfront, with its canteens and brothels, was long ago devoured by large cranes that can empty out a cargo ship in six hours.

The port of Santo Tomás de Castilla is a miniature city in itself, operating 24 hours a day and providing 2,500 direct jobs and as many indirect ones. Cranes with enormous arms move frantically from side to side, lifting boxes and piling them onto the 28-ton trucks waiting in line.

Ever since the 1970s, Guatemala’s Atlantic ports have been used as a conduit for cocaine. It is a six-hour journey by sea to Miami, and the drug would typically be concealed inside fruit, vegetable and shrimp containers. The business was essentially controlled by Cuban exiles in Miami and in Guatemala who enjoyed protection from the army and from a few local entrepreneurs with anti-Castro sympathies. Drug volumes back then were much lower than today’s, but it was still enough to make millionaires out of a few Cuban and Guatemalan business leaders in this country. Later, the business was taken over by small local cartels that were also open to trafficking with migrants and animals, but who themselves depended on the Mexican cartels.

At the port, two narcotics officers are checking a container that’s arrived from Colombia. In their last report on drugs released in early June, European authorities alerted about a spike in increasingly pure cocaine shipments arriving on their coasts, inside containers from Africa and the Caribbean.

According to United Nations figures, 90% of the drug global trade is moved via ships, but only about 2% of cargo gets inspected. The international organization has launched a program to reinforce oversight, aware that ports are a sieve for illegal substances.

“We check nearly everything that comes from Colombia, Venezuela and Panama,” says one of the officers before ordering the goods back into storage, after checking that there is nothing inside save millions of plates and cups made with expanded polystyrene and meant for use by the fast-food industry.

“Do you have a scanner?” I ask.

“No, not yet.”

“So how do you check the nearly thousand containers that pass through here each day?”

“By selecting suspicious countries such as Venezuela, Colombia or Panama.”

“How many dogs do you have?”

“Three, but only one of them is working now, Molly,” he says, pointing at the Belgian shepherd dog playing with a piece of bone.

Puerto Castilla also lacks a refrigerated chamber for inspections, and insurance companies can sue the port for millions if any cargo is damaged, so the officers only check tin cans, plastics and vehicles at a pace totaling around 10 containers a day, around 1% of the total. And this includes containers suspected to be fraudulent in terms of duty. Of the 40 police officers on the team, eight are on narcotics duty, spread out into three shifts. That is two police officers per shift to keep tabs on a thousand containers a day. And Molly.

International organizations feel that there is growing oversight at Mexican ports, and that the traffic of chemical components used to make drugs has shifted to Guatemala.

Santo Tomás de Castilla was operated by the army for decades, and in recent years it has become the perfect goldmine for the political class thanks to the intricate web of businesses, suppliers, clients and operations that take place at a port that handles 30% of the country’s commerce. Former president Otto Pérez Molina and his deputy, Roxana Baldetti, were jailed in 2015, among other things for coming up with phony contracts for port cranes in a case known as La Línea.

“It’s not that the state is absent from here, of course [the government workers and politicians] are here, but only to steal,” says a union leader speaking at his desk just a few meters from here, and who asked to remain anonymous because of the serious threats he has already received.

After a long interview exploring the wonders of Izabal, the governor huffed. For 64 minutes, sitting at his wooden desk, Erik Bosbelli Martínez had explained how this is Guatemala’s second-largest department, how it is “blessed by God” because of its wealth of natural resources, how it contributes 4% of the state’s revenues through mining, tourism and its ports, and how it is the only department that borders with the Caribbean.

The governor is speaking under an enormous portrait of President Jimmy Morales and another one of himself hugging his wife. But when he explains why there have been five governors in under three years, the institutional rhetoric disappears: “It’s too troubled,” he huffs.

In contrast with Mexico, Guatemalan governors are decorative figures with hardly any budget to work with. Bosbelli admits that the most that he hopes to achieve in terms of a legacy is a clean river. Gangs and migrants from Honduras are the biggest problem he has had to deal with since he took on the job seven months ago.

Are the gangs behind the taxi drivers’ deaths? I ask

“Yes, well, them and the Honduran migrants who pass through near here, through Corinto, in long convoys,” he replies.

The migrants or the gangs?

“Well, they’re migrants who want to become gang members.”

“But they’re different things...”

“Yes, well, better to ask the police.”

I ask whether the gangs are behind the taxi drivers’ deaths.

“Yes, well, them and the Honduran migrants who pass through near here, through Corinto, in long convoys,” he replies.

“The migrants or the gangs?”

“Well, they’re migrants who want to become gang members.”

“But they’re different things...”

“Yes, well, better to ask the police.”

Equating gangs and migrants, a technique used in the past by US President Donald Trump, provides the perfect excuse for incompetence.

Joseph Conrad portrayed port cities as places where fever and stories were exchanged, while Maqroll, the sailor created by the novelist Álvaro Mutis, saw them as a blurry threshold between the land and the sea. A port’s importance is measured by the illustrious characters who have lived there: Bowles and Hemingway brought fame to Tangier and Havana. But run-of-the-mill ports are happy with anyone who bothers to pass through.

In the last century, three salient individuals have been to Puerto Barrios. In 1935, actor Bruce Bennett spent a few nights here during the filming of The New Adventures of Tarzan. The black residents of Livingston and the Maya people from Izabal provided filmmakers with a perfect combination for their scenes of savages interacting with the white man.

Nearly 20 years later, in 1954, Ernesto “Che” Guevara was in Barrios during his second trip across Latin America. He was 25 and he worked at the port for a few weeks unloading tar barrels, as he told his mother in a letter. Che wanted to feel first-hand the renovating breath of socialism under Jacobo Arbenz, who had dared to expropriate part of the land owned by the United Fruit Company, which until then had held 50% of all cropland in Guatemala.

A one-hour drive from Puerto Barrios, there is a municipality called Morales. To reach this place, one has to follow the road toward the Atlantic and exit at Km 245, at a spot marked by the gas station of La Ruidosa. The station’s glass door has a bullet hole in it, as an ominous reminder that we are entering the domain of the Mendozas.

Morales does not have a lot going for it; its only notable elements are the homes of the drug lords who live here. But it is strategically located on a crossroads connecting the coasts of Guatemala and Honduras with inner Mexico through the Petén department. The drug lords concentrate their power in this town without bars where the only celebrations are the ones that they allow. Morales has been to the Mendozas what Sicily was to the Corleones: the hub from where they’ve operated their illegal businesses and run a network of transportation firms, construction companies and gas stations owned by themselves.

This is a family clan whose name is pronounced in whispered tones, just like the Lorenzanas or the Leóns. In Guatemala, unlike Mexico, two and even three large drug families can coexist in the same place. This is the case in the departments of Izabal, Petén or Zacapa. On the Caribbean coast and on the border with Honduras, nothing moves without their knowing about it, and that is why Mexican kingpin Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán chose this place in 2011 to go into hiding. El Chapo is the third illustrious visitor to have graced Puerto Barrios with his presence.

After the death of the Mendoza patriarch, his four sons (Obdulio, Milton, Alfredo and Haroldo) took over the family business, and they currently move between Morales and Petén. Their houses are still here, and they stand out from the rest. Haroldo’s is painted a salmon color and it has a private gym in the basement. Obdulio’s has a stone façade and a tiled roof with little lights. Another brother, Edwin, has a home featuring a white entrance door half a block in size. And Haroldo’s other property is a beautiful building with two enormous Bougainvilleas, balconies and a tiled roof. Somebody who knows them well has been pointing the homes out to me.

Although the Mendoza name still commands fear and respect, a police officer who has been with me on my rounds admits that they have lost a lot of firepower and their ties to political power. The capture of the Mendoza patriarch, the arrest of El Chapo and the conviction in a US court of Sergio Mejía, aka El Compa, who operated the Sinaloa cartel in the area, have all contributed to their weakness, and “there are new, smaller groups now who close their deals in Colombia,” says the officer.

A line of Kenworth trucks with 20 wheels and 400 horsepower engines crosses Puerto Barrios like a herd of stampeding bison.

One of the dives that still survives amid the port’s decadence is Medellín, a brothel located across the road. This place is so sordid that to call it a nightclub would twist the latter concept out of shape. Fifteen drunks are staring at the screen, which is showing European soccer while reggaeton music blares out of the loudspeakers. Over at Exa, the other brothel, drinks are 15 pesos more expensive (less than a dollar) because this place has air conditioning, explains Virginia, a 20-year-old prostitute from Honduras. Virginia hates Puerto Barrios, but she offers a masterful lesson in adaptation as she explains how, only last week, she was able to close a deal for oral sex with a Chinese client thanks to Google’s translation service.

It is nearly midnight and I need to find a taxi. The surprising thing is that one shows up despite the curfew. In the end, just like Conrad’s sailors, Puerto Barrios has not a future but a destiny, and there is more literary depth to this place than it would seem.

About this project

The unknown border of America

José Luis Sanz / Javier Lafuente

It has been ignored for decades. The strip of earth that connects Mexico with Central America is not as photogenic as a wall, nor does it have the myths that cinema and the American media have brought to the Río Bravo or the deserts of Arizona. It has been treated like just another Latin American border: disorderly, wild, porous and silent. But it is a dividing line that is crossed by more people ever day than anywhere else in the American continent, one of the busiest in the world. It’s an obligatory crossing point for the hundreds of thousands of Central Americans who are heading north. More than 120,000 migrants have been detained in Mexico every year for the last five years. It is estimated that 90% of the cocaine that will arrive in the United States has touched Central American soil at some point, before it is moved across the border with Mexico. It would be careless to talk about migration and drug trafficking in this region, without paying attention to this area.

The remoteness of the United States from this border aggravates the lack of interest for the area: a faraway border that can’t be counted in cities, but rather villages, hamlets and homesteads. The stories are not told in the voices of governors, but rather mayors, community leaders, soldiers, farmers and coyotes. To understand this border you have to lose yourself in the territory.

It’s a border characterized by difficult terrain, and is difficult to access along much of it. Some of its municipalities have their own languages and sometimes their own laws of silence. Many of the communities that have been forgotten – and assaulted – by the Guatemalan state – such as the Queqchís or the Cakchiqueles, take greater refuge in the innermost parts of this border. And other peoples, such as the Mennonites from Belize, found the perfect area to settle and build a life in these lands. In many parts, the “state” is a diffuse concept. Almost all the security policies of the successive Mexican governments in the last three decades have operated in this piece of earth, in which North America stretches out to become an isthmus. But neither the implementation nor the failure of these policies has merited more attention than a few short sentences. Until now, the southern border has lived and evolved far from the spotlights and far from uncomfortable questions.

The anti-migration maneuvers by Donald Trump have brought a new era of attention. The pressure he has been exerting in a bid to get Mexico to more aggressively control the flow of migrants, and his recent agreement to see Guatemala become the first recipient of deportees for the rest of the Central America region, led to the militarization of parts of the border. From the Central American side of the Suchiate River, Trump has found a comfortable silence: none of the three presidents from the northern Central American triangle – which accounts for more than 90% of the migrants who cross the border with Mexico – have publicly spoken out about the Mexican and US governments’ deal to build “the wall” for the north in this part of the south.

Also, the construction of the “Mayan train,” with which President Andrés Manuel López Obrador wants to connect Cancún with Palenque, passing by Tenosique, promises to transform the area. In both cases, it is unclear what kind of an impact the new policies will have, not just in terms of the ecology of the area, but also for the migratory, labor and criminal ecosystems in this part of the American continent. The southern border of Mexico is a great unknown, one that is rapidly mutating.

EL PAÍS and EL FARO have joined forces to try to explore this territory, and tell its stories. As part of the alliance that we began in April to explain Central America outside of its borders, over the next six months joint teams of journalists from both media outlets, more than 20 people in total, will work to divulge the identities, conflicts and questions that the area hides, narrating them in different parts and multiple formats.

It’s a risky strategy, not just due to the complex reality that we are trying to show but also due to the characteristics of the area, which is one of the most forgotten and violent zones on the planet.

We aim to delve into places that we think we know, such as Tapachula or Tecún Umán; at the same time as we penetrate more inhospitable and secluded parts such as Xcalak, Ixcan, Bethel and Laguna del Tigre. We will try to illustrate a mosaic formed by indigenous Mayans, Garifunas or Mennonite settlers; human flows that begin in Central America, Africa or Asia; by large swathes of legal and illegal crops; poverty, inequality, political powers and armed groups that are constantly changing; through countries that start to fall apart before your very eyes.

Chapter two of Southern Border is coming soon.

Credits

- Project directors: Javier Lafuente, José Luis Sanz

- Coordination: Guiomar del Ser

- Editing: Óscar Martínez, Jacobo García

- Design and infographics: Fernando Hernández

- Front-end: Nelly Natalí

- Texts: Jacobo García, Óscar Martínez, Roberto Valencia, Elena Reina, Carlos Martínez and Carlos Dada

- Video: Teresa de Miguel, Héctor Guerrero, Gladys Serrano, Mónica Campos

- Photos: Héctor Guerrero, Fred Ramos, Mónica González, Víctor Peña, Gladys Serrano

- Social networks: Anna Lagos

- Text editor: Ana Lorite

- Editing and video graphics: Sonia Sánchez Carrasco, Eduardo Ortíz

- Audio editing: Teresa de Miguel

English version by Heather Galloway, Melissa Kitson and Susana Urra.