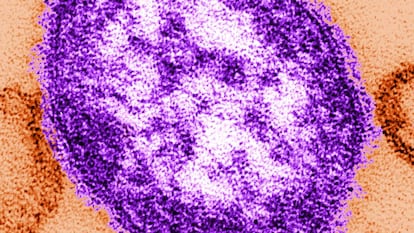

There is only one excuse for not using the measles vaccine

The inoculation against the disease is safe, efficient and cheap. Having access to it and not making use of it is unjustifiable

Even if they’d tried, Europeans couldn’t have done a better job of causing the current outbreak of measles. In the wide and varied region, there are countries that have been rocked by the economic crisis (Greece, for example), by conflicts (Ukraine) and by trends (Germany and Italy). And the result, the one that the World Health Organization (WHO) has been warning about, is that in the first six months of this year there have been 41,000 cases of, and 37 deaths from, an easily preventable disease in one of the most prosperous areas of the planet.

In the first six months of this year there have been 41,000 cases of, and 37 deaths from, an easily preventable disease

If anyone still had doubts, here’s yet another reminder: the measles vaccine was invented in the 1960s, it is safe (no, vaccinations do not cause autism), efficient and cheap (in the US it is estimated to cost less than a dollar per child; in Spain, where it is sold together with the mumps and rubella vaccines (MMR), it costs less than €40).

So there is only one excuse not to use the vaccine: if it is unavailable. It is understandable that this crisis is having its greatest effect in Ukraine, which has been mired in a conflict with Russia for years now. And that in Greece, whose health system has been devastated after years of cuts, there are distribution problems. This is what still happens in a lot of poor countries, where, until now, the worst effects of this and other preventable diseases are concentrated (nearly 90,000 deaths from measles in 2016 worldwide, according to the WHO). The other possibility is that the vaccination is available, but that people can’t or won’t pay for it. In this respect, the WHO mentions the “peculiarities” of the French health system, which is the same as pointing to copayment. The conclusion is that having the vaccination and not using it is simply unjustifiable.

The problem with these kinds of pharmaceutical is that, inexplicably, it is hard to make them popular. Their main benefit is that they save lives (according to the WHO, the measles vaccine has saved 20 million lives since 2000, when a universal vaccination project was started). But given that vaccines have been in use for more than half a century, we have forgotten what the world used to be like before. What’s more, while it is true that there are children who won’t get sick if they go without vaccinations, this is because those around them have, preventing the pathogens from reaching them.

Given that vaccines have been in use for more than half a century, we have forgotten what the world used to be like before

To cap it all, in recent years vaccines have had to deal with competition that sounds a lot more alluring: natural, alternative remedies. When you don’t have children, or you do but they are in good health, it must be hugely gratifying to be one of the smart ones, those who know the hidden truth, those who break away from the herd that subjects their children to treatments that, they claim, only serve to make the evil Big Pharma companies even more wealthy. It’s easy to be original when those who aren’t have got our backs. As Stanley Plotkin, the inventor of the rubella virus, told EL PAÍS last year in an interview: “Anti-vaxxers have no scientific proof, they just like feeling special.”

Obviously, this attitude against vaccines is an indulgence that the rich can afford – like drinking unpasteurized milk (has anyone considered drinking untreated water?). In poor countries they are desperate for these pharmaceuticals to arrive.

English version by Simon Hunter.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.