Nicolás Maduro and the banality of evil

This article is a blow-by-blow dissection of the statements made by the Venezuelan president in a recent op-ed published in EL PAÍS

It was Hannah Arendt who noted how banal evil can be. After attending Adolf Eichmann’s trial in 1961, Arendt wrote that the thing that surprised her the most was just how dim-witted and anodyne this monstrous human being really was. The SS officer was one of the key organizers of the machinery that murdered more than six million men, women and children. Arendt says that Eichmann was not very intelligent. He was unable to finish high school or vocational school and only found employment as a traveling salesman thanks to family connections. For Arendt, Eichmann took refuge in “stock phrases and self-invented clichés” and “officialese.” One of the psychologists who examined him reported that his only unusual characteristic was that he seemed more normal in his habits and language than the average person.

Naturally, there are big differences between Adolf Eichmann and Nicolás Maduro. But there are also similarities. Maduro did not do very well in school or in his working life and his grammatical slips continue to go viral and global on social media. Stock phrases, clichés and officialese saturate his vocabulary. And like Eichmann, his banality is already legendary.

The Venezuelan president recently published a revealing opinion piece in EL PAÍS. It documents his mendacity, confirms his banality, and lays out his immense cruelty.

He begins by stating: “Our democracy is different from all others. Because all the rest ... are democracies formed by and for the elites.” It turns out that the opulent elite created by Hugo Chávez, and perpetuated by Maduro, has spent two decades illicitly enriching itself, all the while exercising power with scant regard for democratic norms. The president’s control over every government institution is absolute. Just one example: between 2004 and 2013, the Venezuelan Supreme Court issued 45,474 rulings. How many of these came down against the government’s position? Not even one.

Maduro did not do very well in school or in his working life and his grammatical slips continue to go viral and global on social media

Maduro continues: “The revolution changed and became feminist. Together we decided to remove sexist violence from our healthcare system and empower women through a national humanizing childbirth program.” Yet, according to The Lancet, a medical journal, maternal mortality in Venezuela has increased by 65% in recent years and infant mortality by 30%. This is what he means by “humanized and feminist childbirth”?

But Nicolás Maduro doesn’t just care about mothers. He is also worried about young people: “Twenty years ago, before our Bolivarian revolution began, it was normal to blame youth unemployment on the youth themselves...who, because they were lazy, deserved poor healthcare, starvation wages, and to live without a roof over their heads. But with us in power, things have changed.” In this the president is quite right, things have changed. The purchasing power of the minimum wage has fallen 94.4% from its 1998 level. In practice, the real minimum wage “on the street” is a little more than $3 a month (€2.50). One month’s worth of the “official” minimum wage is only enough to buy four pounds of chicken. And not all workers are lucky enough to make that much. A nurse who works on her own, for example, earns the equivalent of $0.06 a day. But there is more: the young people who the president is so worried about are the most frequent victims of the runaway crime that has paralyzed the country. Today Venezuela suffers one of the highest murder rates in the world. What has Maduro done about that? Nothing.

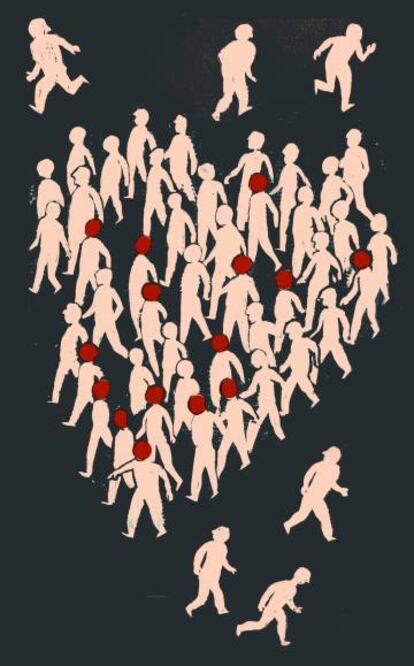

Naturally, the president’s priority is the people: “It is essential that the economy be at the service of the people and not the people at the service of the economy... The economy is the heart of our revolutionary project. But in my heart, the people come first.” These people who apparently fill the president’s heart are currently being decimated by Latin America’s first bout of hyperinflation in the 21st century, as well as appalling shortages of food, medicine, and other basic products. According to the International Monetary Fund, prices will rise 13,000% this year. Last year 64% of the population lost, on average, 24 pounds in weight because they could not afford enough food. This year the shortage is even worse and there is severe rationing of water and electricity. It’s a good thing that Maduro’s economy is at the service of the people. Just imagine if it wasn’t.

In addition to using his column to display his economic and social leadership, the president of Venezuela also reaffirmed his democratic credentials: “For us there is only freedom and democracy when there is someone else who thinks differently out in front, and also a space where that person can express their identity and their differences.” For hundreds of Venezuelan political prisoners, this “space” is a small, crowded cell where they live in inhumane conditions and where some of them are regularly tortured, as has been denounced by all the major international human rights organizations. In the Venezuela of Chávez and Maduro, thinking differently is dangerous.

According to The Lancet, maternal mortality in Venezuela has increased by 65%. This is what he means by “humanized and feminist childbirth”?

To “deepen” the democracy that reigns in his country, Maduro has called for early elections and he is one of the candidates with the best chances of winning, despite the fact that his government has been unable to contain the famine, the health crisis or the murders. “We have been passionately committed to transparency, in respecting and enforcing the voting laws for the upcoming elections on May 20... And this process will be clean and exemplary.” The small detail that the president omitted was that 15 governments in Latin America, plus the European Union, the United States, and Canada have denounced the impending elections as fraudulent and have announced that they will not recognize their results. Maduro – the self-proclaimed democrat – disqualified the main opposition parties. The most popular candidates are in prison, exile, or were barred from standing, and the government is not allowing independent international observers to monitor the electoral process. But the president is not alone. The great Russian democracy will send a team of observers to guarantee the vote’s fairness. Cuba and Nicaragua are sending monitors, too.

It is utterly revealing that, in his long piece, Maduro never acknowledges the hellish conditions that Venezuelans are currently enduring. In surveys that measure the level of happiness in different countries, Venezuela used to hold one of the top spots. Today it is one of the unhappiest places in the world. It ranks 102 among the 156 countries surveyed. Maduro also failed to comment on the millions of Venezuelans who have been forced to leave their homeland.

Perhaps the most outrageous peculiarity of the Chávez and Maduro regimes is the criminal indifference they have shown to the suffering of the Venezuelans who they claim to love. The indolence, the indifference, the passivity with which Maduro deals with this tragic crisis that is still growing and expanding, killing more and more Venezuelans every day, seems not to affect him in the least. It does not move him or motivate him to act or to seek help. On the contrary, Maduro steadfastly denies that Venezuela faces a humanitarian crisis at all and has refused the international aid that could have already saved thousands of lives.

Yes, Maduro is banal. But he is also deadly.

Moisés Naím is a columnist for EL PAÍS. Twitter: @moisesnaim

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.