Lisbon: Portugal’s capital of cool

We explore a city that combines faded splendor with a dynamic entrepreneurial culture, one that has long been overlooked, but is now undergoing an unprecedented revival – but the process has had its critics...

Every year, on April 25, communists gather on Libertad avenue to mark the Carnation Revolution of 1974. Several weeks later, on June 12, the wide boulevard is overrun with would-be brides hoping that St. Anthony, the matchmaker saint, can help them find a husband.

This leafy thoroughfare, with its artistically designed cobblestones, stretches all the way to the River Tajo, where, five centuries ago, navigators set sail in search of adventure. Following this intense era of exploration, Portugal went into hibernation, with its citizens making do with what little they had. This was a period that lasted until… well, now.

Today, Lisbon finds itself gripped by the kind of passion and ambition that few of its residents – including its politicians and businessmen – are familiar with. Perhaps the new vibe is due to an influx of young tourists or perhaps it is simply the result of a city kicking back after an excruciating economic crisis. Whatever the reason, Lisbon is unrecognizable. “This area was scary 10 years ago,” says Brazilian Rodrigo Azambuja. “The country was a wreck.”

Foreign investment arrived with the change in the Rent Act in 2012, taxation and visas

Architect André Caiado

A designer of bespoke carpets, Azambuja knows what he is talking about. He landed in the historic Chiado district in 1989, a time when many of its buildings were derelict. “There have been other golden moments, like when we had the World Exposition or when we joined the euro, but this is different,” he says. “This is the first time we’ve had cool, young tourism en masse.”

With its rainbow of colored yarns and tapestries lining the walls, Azambuja’s studio resembles more a museum than a workshop. A huge computer used to reproduce geometrical figures and colors contrasts with the timeless ambience. Recently, a bank commissioned a 63-square-meter carpet, which took dozens of embroiderers four intense months of work to produce. “We sent the client regular pictures updating them on how the order was coming on,” he says. “They love being able to see that it really is a unique piece of work.”

With a cigarette burning between his fingers, Azambuja cooks a rice dish while guests pile into his home. He admits he is not not good at saying no, so what was originally meant to be a gathering of 10 is now a party of 40. “I’ll just add more water to the pan and it will feed everyone,” he says with a smile.

His guests are a mishmash of moneymen, musicians, politicians, neighbors, TV stars, and linguists, hailing from Switzerland to Seville and who speak four languages around the table as if it were the most normal thing in the world.

This is not the only house in Lisbon with an international feel. In another apartment block, the director of the Maria Matos Theater, Mark Deputter, gets half the shows he puts together from abroad. Quality is everything. Even if it’s just for a day, he signs up the latest on the international circuit, be it a Lithuanian operetta or a Farsi comedy act.

“We can compete in quality, if not in quantity,” says Joana Hecker, a New Yorker who came to Lisbon on a research grant for several months and is still here five years later. “Creating small but strong, unique and dynamic communities. Money is the only religion in New York, so people only do things if it makes good business sense. Here, I discovered the religion of friendship – of making time for relationships, social life and the community.”

Three years ago, Hecker and her associate, Ricardo Lopes, set up Lisbon Living Room, a company that organizes concerts in private homes. “It started with the need to hear live music in pleasant surroundings,” she says. “Then someone offered to give us the wine and another wanted to provide the tapas. The public pay €10 each; the musicians always get paid double what they would make in a bar and people come explicitly to listen to them.”

They have 1,500 people on their mailing list and a long line of concert-home offers. “People know that there is always something on the last Sunday of every month, even if it’s Christmas,” says Lopes. “They don’t know where it is or who is playing until a few days beforehand. And there’s a certain beauty in this. We have no ambition to grow; we simply want to be defined by quality and character.”

Concert-goers have been treated to jazz by Eurovision winner Salvador Sobral, opera by the soprano Siphiwe McKenzie, as well as performances by pianist Júlio Resende and Guinean balafon player Kimi Djabaté, who is something of a virtuoso when it comes to playing the handcrafted West African xylophone.

A descendant of Mandinka musicians, Djabaté came to Lisbon more than 10 years ago, since when his 2009 album Karam has topped the World Music Charts Europe. Portugal now has more to offer than fado, the melancholic song tradition that has enjoyed a revival over the last two decades. Kizomba, funana, pimbam and African dance music are now heard everywhere in the Portuguese capital. And thanks to the famous Buraka Som Sistema group, a number of schools have sprung up teaching kuduro, an Angolan dance guaranteed to win you kudos on the dance floor if you can master its complex rhythms.

“We are not Anglo Saxon or Latino, but there are elements of those too,” explains 29-year-old Marlon Silva, better known as DJ Marfox, and who has spun at the MOMA in New York. The real temple of this style of African music, however, can be found at MusicBox, a trendy disco under a bridge in Rua Nova do Carvalho, where in the old days, sailors would pick up prostitutes.

“We invested in this street [Rua Nova do Carvalho] because it has a story to tell,” says Roger Mor, from Mainside, a real estate company that deals in concepts and invests in unlikely properties, such as an old five-story brothel, which they have left intact, complete with its tiny rooms that were rented by the hour, its old-fashioned basins and its black-and-white erotic photographs. “No one decent came here,” says Mor, author of Alice in Brotheland, a quirky play acted out on the premises. “We had the idea of painting the street pink. Now everyone knows it as “the pink street” and its main attraction is the Pension Amor.”

Years ago, during the worst of the crisis, Mainside spotted the potential of another run-down part of the city called Alcántara. “We bought a dilapidated factory and turned it into an alternative avant-garde space for Lisbon’s residents. But we were surprised that it also attracted a lot of young foreigners,” says More.

Lisbon will remain one of the world’s biggest attractions. We will hit a growth crisis but then things will stabilize Sara de Paretere

Now more than one million visitors a year come to see what is known as the LX Factory, where innovative art and artists-at-work are often on show. “Our projects respect the history of the place,” adds Mor. “We think its fundamental that Lisbon nurtures all that makes it unique if it wants to retain its charm.”

So far, so good. Today, Lisbon is enjoying the fruits of unprecedented international popularity. Tourism generated 38.6% more business in the first quarter of 2017 than last year and arrivals are up by 26%. Since 2014, around two new hotels have opened a year, while 75% of apartments have been snapped up by foreigners. There is no better way to measure tourism growth, however, than the line outside the famous bakery Pastéis de Belém. “Last year, we made 8.5 million cakes, 1.5 million more than in 2013,” says Pastéis de Belém spokesman Miguel Clarinha.

Some years ago, Miguel Leão emigrated to Norway to set up replicas of the old-style barber shops that had long since disappeared from Lisbon’s streets. Mission accomplished, he returned home to do the same thing here. Now he has Belarmino, tucked away between Principe Real street and Libertad avenue, a favorite with locals and visitors lucky enough to stumble across it.

Leão began with one chair and one pair of scissors. Now he has three chairs and two colleagues working alongside him. “We are genuinely traditional – not hipsters or hairpiece guys, though we can do that too,” says Miguel who lowers his prices for those living in the neighborhood. “Half of the customers are Portuguese, so there’s as much work in winter as in summer. The secret is to speak to the customer. If there’s a personal touch, they come back.”

The Belarmino barbershop owes its name to a renowned Lisbon boxer from the 1950s, immortalized on screen. “I always identified with him,” says Leão. “I grew up in a run-down neighborhood and I made poor choices but I got back on the straight and narrow, thanks to boxing. This shop is my tribute to one of the people who has made Lisbon what it is – and that character is something we must be careful not to lose.”

The City Hall’s ‘Refurbish First, Pay Later’ campaign is driving the make-over of entire districts such as La Baixa, which seemed until very recently to be dying a death. Around 84% of construction money is being pumped into refurbishments – a far cry from what was happening 10 years ago. But in the last five years, the cost of licenses needed to revamp old buildings has multiplied.

Architect André Caiado is behind many of the refurbishments on Libertad Avenue. “This big change in the city hasn’t come about voluntarily,” he says. “It was through sheer necessity and because we were obliged to do it. You only dare to change when you’re on the edge of the abyss. Changing the Urban Lease Act was fundamental, something politicians were never going to do of their own accord because it wasn’t popular. It was only done when the troika demanded it as a condition of saving our country from bankruptcy. With the change in the Urban Lease Act in 2012, as well as the [corresponding] taxation and visas, we started to attract foreign investment.”

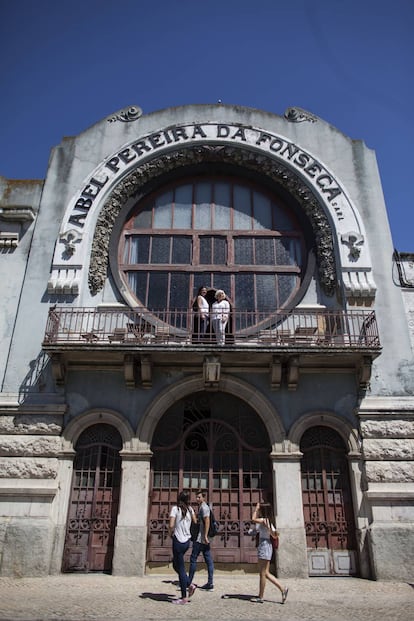

Maria Alvares converted the old Abel Pereira da Fonseca wine warehouse into a workspace for people who want an alternative to an office. Sara de Paretere, her daughter, manages the enterprise, whose clients include New Zealanders, Frenchmen and Americans, as well as the Portuguese. “It’s a center of creativity where everyone benefits because it facilitates communication between different businesses,” she says. “Some 85% of the space is used so there are no surprises at the end of the month.”

Sara de Paretere doesn’t hold with the idea that such places are robbing the city of its identity. “We have many rundown buildings and the city’s policy is to refurbish rather than pull down. The city is as beautiful as it has ever been,” she says.

Fernando Medina, Lisbon’s Mayor, readily admits that external factors have encouraged tourists to visit, such as the current instability in North Africa. And he is also quick to credit his predecessor António Costa, now the country’s prime minister, for the city’s buzz. But it is the Portuguese character that he believes is responsible for much of the success. “In a world where doors are closing, our tolerance has become a very important asset,” he says, pointing out that in the districts of Alfama and Intendente, there is a melting pot of 120 different nationalities. “It’s not forced, it’s just the way we are. Lisbon combines traditional and cosmopolitan culture extremely well.”

While Berlin and Barcelona have long been trendy, they are also having to deal with mounting resentment toward incomers and tourists, while Lisbon is welcoming its visitors with open arms. “Lisbon has two advantages over them,” says the mayor. “The city center, which is where tourists go, was previously the least populated area. Neighborhoods such as Baixa, Chiado, the Mouraria, Martim Moniz and Alcántara have been losing residents for years. Thanks to tourism, they are alive again. The other advantage is that most of the buildings are council-owned. We have a lot of property in the center for housing the middle classes with rents between €200 and €400.”

“We want to retain our influence in the property market so the city doesn’t lose its identity,” says a spokesman for City Hall.

What doesn’t belong to Lisbon City Hall often belongs to the army. In the Beato district, the old military provisions factory once produced 18 tons of bread and pasta a day for the troops fighting in Portugal’s colonial wars. Now, it’s a neglected gem of industrial architecture. Measuring 30,000 square meters and with 20 buildings, this area is being turned into the city’s most modern quarter, welcoming artists and tech wizards into its midst.

“The main thing about start-ups is the race against time,” explains Hub Creativo director Luis Fontes. “In Silicon Valley or London, you get €20,000 to make something of yourself in three months. Here, you have a year to develop your product. But our real competition in Europe for attracting projects is always Barcelona.”

This futuristic district will be a kind of all-inclusive business park, and one pavilion, which was formerly an official residence, will provide the entrepreneurs with accommodation. “They won’t have to worry about finding a place to live,” says Fontes. “They have it right here, at least while they are settling in.”

Start-ups can choose which warehouse to work in. There is something for all tastes here, from the old bakery to a monastery, while the grain silos that block the view of the river will remain because in this city, in this era, nothing is pulled down. “The silos are going to be converted into unique hotels,” says the mayor.

Meanwhile, the old army factory has been turned into the new Web Summit site. Set up by Irishman Paddy Cosgrave, the digital summit drew 40,000 people last November, putting it firmly on the map. The knock-on effect for the city was an injection of €200 million into the economy as hotels, bars and restaurants were run off their feet while news of the event reached 119 countries. This year, attendance is forecast to double. If anyone didn’t know about Lisbon before it, they know now – a third of Portuguese start-ups are foreign.

For the enterprising, Lisbon is flush with potential – there is still an abundance of palaces to convert and the train line separating the city from the river to rehabilitate. “We’re going to do that,” says the mayor with a smile. “We have a plan and the money.”

In a bid to lure tourists away from the Chiado district, attractions are being set up in other parts of the city. This summer, for example, a viewpoint opened on the suspension bridge and refurbishments to the Ajuda Palace were completed – something King Luis I of Portugal failed to achieve in his day.

Sooner or later, a 15-kilometer cycle path will run parallel to the river, connecting the Park of the Nations with the Belém tower. “Ours is a very modest city,” says psychoanalyst Ricardo Lopes, who co-owns Lisbon Living Room. “We’re not at all proud. During the crisis we were about to lose an entire generation, but we have emerged with great strength in almost every sector. Ours is a community that is keen to show its worth.”

Meanwhile, Sara de Paretere is optimistic about Lisbon’s prospects as Berlin and Barcelona’s rival. “We will go through a growth crisis but that will stabilize,” she says. “Berlin doesn’t go out of fashion and neither does Barcelona. What wasn’t normal was how many people didn’t know about the city.”

Rodrigo Azambuja, who moved here 30 years ago from Brazil, also feels that Lisbon is experiencing a cultural apogee. “We have good communications, a quality health service, a safe environment, a tolerant society with respect to race and sexual orientation… It’s true that the price of apartments has rocketed, but it wasn’t long ago that no one wanted them.”

And while some are concerned that encouraging an invasion of tourists and entrepreneurs could ruin the city’s character, American Joana Hecker believes Lisbon has great “interior strength,” which he recognizes needs nurturing in order to protect all that makes the city unique.

Some things, however, never change. In years to come, communists and brides will gather on Libertad Avenue. And though scientist Elvira Fortunato will be developing microelectronics on the other bank of the River Tajo, and the first Mercedes Benz global digital center will be perfecting their driverless car, the city’s soundtrack will continue to be the melancholy ‘fados’ of António Zambujo or Camané. Lisbon – where have you been all my life?

English version by Heather Galloway.