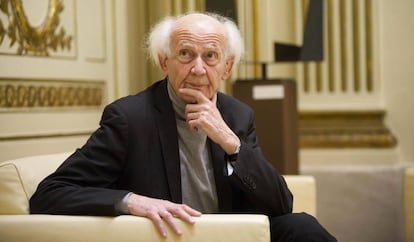

Zygmunt Bauman’s warning from the grave: don’t fear the future

Two essays by idol of Spanish protest movement explore our search for Utopia in the past

Has anyone noticed that science fiction books and movies are increasingly categorized as horror; in other words, science fiction now depicts a future no one would want to live in? For Zygmunt Bauman, one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century, it’s an indication that we have started to seek Utopia in a romanticized past, given that the future is no longer synonymous with hope and progress, as English Renaissance humanist Thomas Moore, who wrote about the subject, saw it.

Before his death in January, aged 91, the Polish sociologist and philosopher wrote Retrotopia, which has recently been translated into Spanish and published by Paidós and, on a similar theme, an essay called Symptoms included in The Great Regression, a collection of works pulling together the international debate on right-wing populism and the state of democracy with contributions from Slavoj Žižek, Nancy Fraser and Eva Illouz, now in Spanish and published by Seix Barral.

“The future is, at least to begin with, malleable, but the past is solid, sturdy and appealingly steadfast. However, when it comes to the politics of memory, the past and the future have exchanged attributes,” Bauman writes.

He doesn’t try to dupe us with new and false promises of the future Marina Garcés of Zaragoza University

Bauman, who fled the Nazi invasion of Poland during the Second World War, eventually settling in the northern English city of Leeds where he was Emeritus Professor of Sociology, writes about multiculturalism, the precarious world our children will inherit and the obsolete nature of our skills as robots replace us. In short, we are scared because everything that was solid is now liquid – a term used by Bauman in his “theory of Liquid Modernity.”

“There’s a deepening gulf between the ability to get things done and the capability of deciding what things need to be done, between what is really important and what is important for those doing and undoing; between what happens and what is desirable,” he wrote.

Bauman points out that we have regressed to a kind of tribal mentality, to the maternal breast, to the kind of pitiless world described by English philosopher Thomas Hobbes to justify the need for a strong state to prevent a continual situation of war. We have also returned to a time of inequality in which “the other is a threat” and “solidarity is a whim adopted by society’s most ingenuous members.” We have returned “to skepticism, foolishness and frivolity, which is a treacherous trap.”

“The aim is no longer to make society better – improving it is a pointless exercise to all intents and purposes. It is to improve the individual’s position within this society, which is so essential and definitively incorrigible,” he laments.

Bauman points out that we have regressed to a kind of tribal mentality

Marina Garcés, a lecturer in Philosophy at Zaragoza University, applauds Bauman’s ability to take the Utopia discourse to its conclusion with all its consequences. “He doesn’t try to dupe us with new and false promises of the future,” she says. “Instead, he tries to understand what is happening in the post-revolution era.”

Inspired by Marx, Bauman quotes the German thinker on a number of occasions in Retrotopia, blaming mass consumption for seducing society. He does not reject scientific analysis of the contradictions implicit in capitalism, but uses other arguments to offer a more complete vision of what is happening, says Manuel Cruz, professor of Philosophy at Barcelona University and a Socialist Party (PSOE) deputy. “Throughout the 20th century, the idea that we have missed the opportunity for Utopia has is a constant theme, but Bauman makes an effort to recognize what the new reality brings,” he says. “The thinkers we now consider revolutionary were at the time met with an attitude of, ‘we already knew that.’ Society needs time to understand what new ground is being broken by thinkers.”

In both Retrotopia and Symptoms, Bauman outlines the challenge ahead and offers an abstract and skeletal response to it. The challenge is “to design, for the first time in the history of man, integration, without resorting to any division.”

The future is malleable, but the past is solid, sturdy and appealingly steadfast Zygmunt Bauman

Until now, he argues, society has resorted to the division between us and them and we keep looking for a “them” who is “preferably the typical outsider, undeniably and incurably hostile, always useful when it comes to reinforcing identity, determining borders and building walls.”

However, this historic dichotomy will not work in the multicultural scenario in which we now find ourselves. The only viable response to the new reality is, according to Bauman quoting Pope Francis: “The capacity to dialogue.”

Garcés admits to being surprised by both Bauman’s call to dialogue – dialogue between who, he wonders – and his reference to the pope. “I think it is a cry for help from Bauman as he tries to use universal language to describe our situation. He knows that there are no partial solutions anymore to any of the problems of our time,” he says.

The final warning from the Polish thinker reads: “We should get ready for a long period that will be characterized by more questions than answers and by more problems than solutions […]. We find ourselves more than at any other time in history in a real quandary: we either join hands or we join the funeral procession of our own burial in a mass grave.”

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.