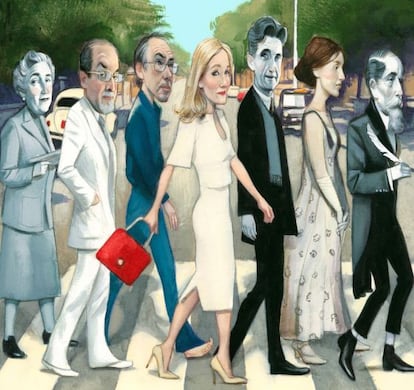

All you need is books

Britain, the guest at the 2015 Guadalajara Book Fair, is consecrating its famed ’80s generation

Like so many good stories, this one begins in a pub: The Pillars of Hercules, in London’s Greek Street, above which the offices of The New Review, a literary magazine run by Ian Hamilton in the latter half of the 1970s, were once located.

The pub soon became the magazine’s de facto office, and the place where Hamilton, whisky in one hand and cigarette in the other, would hold court amid a coterie of soon-to-be famous writers.

There was a feeling that this was the start of something new. It was a time when being a novelist was sexy”

Sam Leith, book reviewer

Ian McEwan, Julian Barnes, Christopher Hitchens and Martin Amis would go there to discuss literature, drink, and occasionally earn a few pounds to keep them going. “It was, and remains, a brotherhood, a family,” says McEwan. “Many writers from my generation were all about to publish their first novel, and that pub became the place we hung out in.”

The Pillar of Hercules was the site where one of the most extraordinary literary phenomena of recent history was born: a group of writers determined to break the rules, and whose global success continues to influence British writing four decades on.

Many of these writers, now in their sixties, remain hugely popular, and their novels continue to sell around the world.

“What made that generation so special is that there hadn’t been anything, at least since the war, that produced such an enthusiastic feeling,” says Bill Buford, the US writer who, as editor of literary quarterly Granta, would play such a key role in the resurgence of the British novel. “It was the noise after the silence. The oasis comes after the desert: there can be no oasis after the oasis. But the truth is that when they arrived, Britain was not an exciting place for books, and now it is. They were celebrated because there was nobody else; nowadays there are a lot of people doing interesting things.”

The UK is still a literary powerhouse, a place where more than 180,000 titles are published each year, generating annual sales of €4.6 billion, 40 percent of which comes from exports. Thanks to the likes of Hilary Mantel and J.K. Rowling, historical novels and young-adult fiction are among the most popular genres.

And Britain continues to produce new talent that sells, says Peter Florence, the co-founder and director of the Hay Festival, set up in 1989 and now one of the world’s leading literary events with outposts all over the globe, including in Spain. “Great books come out every year,” he says. “Tahmima Anam, Laline Paull, and Rebecca F. John, for example, are great new writers. I also think that after the sublime genius of Tom Stoppard, the best British bets for a Nobel Literature Prize could be Ali Smith and David Mitchell. But the difference with that generation of the 1980s is that they were all friends; a gang that the media could identify with and write about.”

Sam Leith, author and literary editor of The Spectator, who sat on the judging panel for this year’s Booker Prize, describes Amis et al as: “The last coherent wave we had.” “There are prominent writers around today, but not a closed literary circle. After the tradition of well-constructed and orthodox suburban novels comes along this generation which, as Barnes said, sought to: épater le bourgeois [wow the middle classes]. There was a feeling that this was the start of something new. It was a time when being a novelist was sexy.”

Hurricane Rushdie

British literature flourished under the Thatcher government of the 1980s. “The novel was sexy again,” wrote veteran writer, academic and critic Malcolm Bradbury in his book The Modern British Novel in 1993, arguing that novelists were living proof of the Thatcher miracle, with their preoccupation with lifestyle, their culture of eclecticism, their competitiveness, and cult of success. Bradbury says that post-modernism became not so much a dark experiment but, as with expensive foods imported from exotic countries, an elegant product.

The best indicator of the new direction that British writing was taking was the Booker Prize, the country’s most important literary award. In 1980, the battle was between two giants who had made their name in the 1960s: Anthony Burgess and William Golding, with the latter prevailing. The following year, the winner was an unknown author named Salman Rushdie.

His book, Midnight’s Children, was unlike anything seen before within the British literary tradition. Cosmopolitan and free, not just in content, but also in its effervescence of form, it drew more on Günter Grass and Gabriel García Marquéz than on the greats of British literature. Kazuo Ishiguro described the book as “absolutely crucial” for young writers like himself who dreamed of pushing back the boundaries of the British novel.

The Pillar of Hercules pub became the place where one of the most extraordinary literary phenomena of recent history was born

Midnight’s Children landed on Bill Buford’s desk sometime in late 1979 as a manuscript. Buford, then studying at Cambridge, had begun editing Granta. Buford included an extract from the as-yet unpublished novel in the book-format magazine, which proclaimed “the end of the English novel” and the beginning of “British fiction.”

“British literature in those years was like the English countryside: lovely, orderly, and totally predictable,” says Buford from New York, where he moved in the mid-1990s to edit The New Yorker’s fiction pages. He still contributes to the US publication, as well as writing books about food and cooking. “I was looking for a literature that didn’t exist at that time, not even in the United States, where some experimentation was going on, although it was all very inward-looking. Salman was looking out to the world. He talked about history, about politics, about the world. It was the first book since One Hundred Years of Solitude that had that kind of ambition. It was an explosion, a hurricane of fresh air.”

Let’s not forget that this was the early 1980s, the days of Thatcher, and of Saatchi & Saatchi. Marketing was the new religion and books just another product. So, in the same way that there was a meat marketing board to persuade people to eat British beef, there was also an institution that tried to get British people to buy more British books. And its head, Desmond Clarke, had the bright idea of compiling a list of the 20 best British writers aged under 40 – a move that would become one of the most important marketing coups in the history of publishing.

The Granta list

On August 23, 1983, the list was published in the Sunday Times. Aside from the limited impact that might be expected from a story published during the summer silly season, it should be remembered that hardly any of the writers on the list had actually had anything published yet.

But Buford already had many of their manuscripts sitting on his Cambridge desk. “I had manuscripts of at least 13 of those writers,” he says. “That is what literary magazines can do, listen to the new voices of a generation.” So Buford stuck his copy of the Sunday Times in his briefcase when he traveled to London the next day to meet Peter Mayer, the head of Penguin Books, to convince him to sign a distribution deal with Granta.

Mayer accepted, and at the end of the meeting, Buford pulled out his copy of the Sunday Times, suggesting to Mayer that the next issue of Granta feature that list of new writers.

More than 180,000 titles are published each year in the UK, generating annual sales of €4.6 billion, 40 percent of which comes from exports

Within the 320 pages of that seventh issue of Granta, published in 1983 and called “The Best of Young British Novelists,” were extracts from works by, among others, Amis, McEwan, Barnes, Ishiguro and Rushdie. It opened with the first pages from Amis’s Money, which would be published the following year, painting an unforgettable portrait of the age. The illustration on the cover, two quills slashing at a torn union jack, said it all.

The marketing worked. Narrative with literary ambitions left the fringes and joined the mainstream. Book retailer Waterstones, which had been founded in 1982, displayed the novels as pieces of attractive, eye-catching merchandise. The young novelists became celebrities. Their lives, their novels, their contracts, all of it was considered newsworthy. “It was like the rebirth of British narrative,” says Buford. “By the mid-1970s, it was like a desert, and 10 years later there were many stimulating and ambitious writers around. There was no single style: the only thing they had in common was a pleasure for telling stories, and their own ambition. A country that until then had been inward-looking now began to look outward.”

Soon, British writing was garnering international attention. It even reached the small Costa Brava resort of Platja d’Aro, where a delegate of literary agent Deborah Rogers used to spend the summers, along with a young Catalan publisher named Jorge Herralde.

“We often spoke,” says Herralde, who went on to found the publishing house Anagrama. “Around the middle of the 1970s I began buying titles by American authors that nobody had heard of then. When it became clear that I was interested in English-language literature, I was offered First Love, Last Rites, Ian McEwan’s first collection of stories. Then came Amis, Kureishi, Ishiguro, Barnes… I used to call them the dream team. We have continued to publish their work in Spanish and today they are an important part of our catalogue. They have been well received by the critics and the public, both in Spain and Latin America.”

Midnight’s Children drew more on García Marquéz than on the greats of British literature

The 1980s ended symbolically and dramatically on February 14, 1989, when Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khomeini, issued a fatwa against Salman Rushdie, calling on the faithful to murder the writer for having blasphemed against Islam in The Satanic Verses.

Since then, Granta has published three more special issues – one per decade – dedicated to the 20 best British writers under 40, helping launch the careers of Irvine Welsh, Nick Hornby, Jonathan Coe, Adam Thirlwell, Sarah Waters and Zadie Smith.

Sam Leith sees a number of trends: “There’s a lot of present-tense narrative, a lot of structures using twin timelines, a lot of real people, a lot of novelized history,” he explains. “And above all, the diversity of the United Kingdom is reflected through the work of second and third-generation immigrants. It’s a phenomenon that began in the 1980s, but has since been assimilated.”

In the same way the changes wrought by Thatcherism arguably propelled a generation of young writers into the limelight, the ongoing financial crisis has proven a powerful literary stimulus. “Anxiety about identity ends up being reflected in writing,” says Leith. “Scottish independence, the immigration debate, relations with Europe, the end of political consensus… all these things feed an identity debate that will be interesting for writers. But these phenomena will take a few years before they’re reflected in literature. So perhaps we’ll have to wait.”

The Guadalajara International Book Fair will be held between November 28 and December 6 in Mexico. The United Kingdom is the guest of honor. More information: www.fil.com.mx

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.