France makes amends for treatment of Spanish Civil War refugees

Rivesaltes internment camp was used to hold “undesirables” throughout World War II Even in this century it was still utilized as a holding center for migrants without papers

Between 1939 and 2013, the small French town of Rivesaltes, some 30 kilometers from the Spanish border, was the site of one of the most shameful chapters in French history.

Located on a barren, windswept plain, the ruins of the 650 barracks and latrines of what was Western Europe’s largest concentration camp, covering more than 600 hectares, can still be seen.

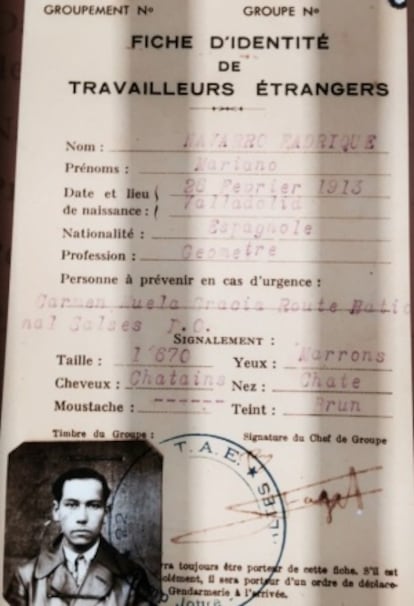

More than 60,000 “undesirables” were housed there: first came Spanish refugees fleeing the Civil War; after France capitulated to Germany in 1940, Jews and Gypsies were kept here before being sent to the Nazi death camps in Eastern Europe; after the war, collaborators and German POWs were kept there; and then, following Algerian independence, the harkis, Algerians who had fought for France were kept there; and finally, until just two years ago, migrants without papers.

On Friday, the French Prime Minister, Manuel Valls, unveiled a memorial to them.

In 1939, half-a-million Spaniards poured into this corner of France, tucked away between the Pyrenees and the Mediterranean. Among them was Victoriano Gómez Díaz, an officer in the Republican army.

“He slept on a bunk bed in very damp conditions. There were fleas, lice, bedbugs, scabies… The food was terrible and there wasn’t much of it. They were cold all the time, and the guards, many of them Moroccans, used to beat people,” says his daughter, Rosy Gómez, who lives in Argelés-sur-Mer, close to the vast beach where Spanish refugees were kept before being sent to other camps.

Gómez is the president of an association that represents the children of exiled Spaniards, and that each year organizes a march that retraces the routes taken by Spaniards over the Pyrenees. Now aged 63, she is still moved as she tours the camp, pointing to reminders of the past. “My father made this ring from animal bone,” she says

Few Spaniards who were in the camp are still alive; among them is Gilbert Susagna. Aged 80, he now lives in the nearby town of Perpignan, and was at Friday’s ceremony. He was kept here with his mother in 1941. “I was aged five. But because I was a child I don’t have any bad memories,” he says. His father, a communist, had been the mayor of his tiny village in Lledia province. He lost a lung during the battle for Madrid and fled to France in 1939. “My mother told me the Jews and the Gypsies had a terrible time of it. I didn’t have such a bad time, but it has left its mark on me all my life,” he says.

Almost half of the 20,000 Spaniards who passed through Rivesaltes were sent to Nazi concentration camps; of them, 65 percent died. Of the 7,000 Jews interned there, 2,300 were murdered by the Germans. “My father was due to be sent to Mauthausen in 1941, but at the last moment, a friendly hand pushed him to one side as they were being loaded on the train,” says Rosy Gómez.

Walking through the camp today, it is easy to get an idea of the terrible living conditions. Each barracks was 30 meters long by six meters wide, and five meters high. The thin walls and ill-fitting windows and doors made them ovens in summer and freezers in winter. “It was terrible: the diseases, the cold… The wind, the wind, was what survivors I have talked to told me about. The children were thrown about,” she says during a visit to the camp with Denis Peschanski, a member of the committee that oversees the camp’s new status as a memorial. His father fought with the international brigades during the Spanish Civil War and was later interned in several French camps.

It would be a good idea if Spain also looked into its own dark past. A people without memory cannot build a real democracy”

The French authorities have tried several times to clear the site. The last attempt was in 1998, when thousands of archives relating to the camp were found on a nearby garbage tip. But civil associations, organizations such as Rosy Gómez’s, and some in the local and regional administration managed to block the move.

Among them was the mayor of Argelés, Pierre Aylagas, the son of a Spanish republican who was held in several French prison camps, among them Rivesaltes. “I have worked hard to make this camp into a memorial because I remember the values I have always defended,” he says.

The museum, designed by Rudy Ricciotti, is a 4,000 square meter, windowless oblong cement block, most of which is underground, so as not to overshadow the tumbledown barracks nearby. Inside, is a permanent exhibition explaining the camp’s history through photographs, videos, maps, an auditorium, and a teaching area for students and teachers.

“This is a symbol of one of France’s least glorious periods, but at last it is being recognized,” says Geneviève Dreyfus-Armand, a renowned international expert on the exile of Spanish refugees who fled Franco’s Spain, and who is critical of what she sees as Spain’s failure to remember its own past. “It would be a good idea if Spain also looked into its own dark past. A people without memory cannot build a real democracy. We must never confuse the executioners with the victims.”

Present at Friday’s commemoration were Valls and three other members of the French government, along with members of organizations representing the families of those interned here. No members of the Spanish government or any official entity attended.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.