Judge shelves case of cameraman killed in Iraq war, citing law changes

New interpretation of universal jurisdiction reform leaves High Court powerless to continue

“The light can no longer remain turned on.”

With this sentence, High Court Judge Santiago Pedraz admitted that it has become impossible to keep investigating the death of a Spanish cameraman who was covering the 2003 invasion of Iraq by allied forces.

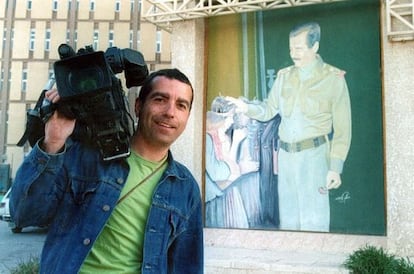

José Couso died on April 8, 2003 during a tank shelling of the Hotel Palestine, where he and other journalists were staying. In 2005, three US servicemen were targeted in a criminal inquiry by Spain’s High Court, and the case has been dragging on ever since, despite behind-the-scenes pressure by the American embassy to get it shelved.

Until the Supreme Court’s decision, the judge felt that the universal jurisdiction reform still left enough leeway to pursue the investigation

But the government’s 2014 universal jurisdiction reform, which severely curtailed Spanish judges’ ability to pursue crimes committed outside national borders, has delivered the final blow to the long-running case.

The controversial reform was triggered by China’s anger when several former and current high-ranking officials were targeted in a Spanish court investigation into genocide claims in Tibet.

In a statement released Tuesday, Judge Pedraz deplored this reform, which “prevents the persecution of any war crime committed against a Spaniard save in the unlikely situation that the alleged culprits have taken refuge in Spain.”

The magistrate underscores how Spaniards will be legally unprotected in similar cases that might arise in future.

“Faced with such a crime committed against journalists or persons considered to be part of the civilian population (such as aid workers), neither the relatives nor the prosecutors will be able to request the opening of proceedings to at least identify the victim, request an autopsy or other urgent procedure, or investigate the circumstances,” writes the judge.

Pedraz, who once traveled personally to Baghdad to visit the site of the shelling, said that a recent Supreme Court decision shelving the Tibet case on account of universal jurisdiction reform sets a precedent for all other international cases.

Until then, the judge felt that the reform still left enough leeway to pursue the investigation because of the international treaties that Spain is a signatory to, such as the Geneva Conventions, which force states to pursue war criminals no matter where they may hide.

But on May 6, the Supreme Court entered a judgment that went in the opposite direction, stating that “Spanish tribunals lack the jurisdiction to investigate and try crimes against protected individuals and assets in the event of an armed conflict abroad.”

The only exception to this, the Supreme Court feels, is if the suspects are Spanish or foreigners whose regular place of residence is Spain.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.