Witness accuses Iguala mayor of personally assassinating a rival

Kidnap and torture survivor watched José Luis Abarca shoot a labor leader in the face

Nicolás Mendoza Villa is a survivor.

In the early hours of June 1, 2013, after he himself was kidnapped and tortured, he watched the mayor of Iguala, José Luis Abarca Velázquez — recently arrested over the disappearance of 43 students from a teacher’s college — personally shoot a political rival in the head.

The victim, Arturo Hernández Cardona, was an engineer and leader of Unidad Popular, a movement that defends the rights of land workers.

That was when Mendoza figured that he was next to die.

“I just asked for my body to be left near a road so my family could find it,” he recalls.

But fate saw another outcome. While he was being transferred elsewhere for his own execution, Mendoza managed to escape and flee across the countryside. Since then, he has been a fugitive in his own land, and the drug cartels have put a price on his head.

Mendoza has had to leave Iguala and scatter his family, and he now lives in miserable conditions. His house was twice ransacked by hitmen. He knows they are looking for him and have orders to kill.

Although he is not the only person to have witnessed the killing, Mendoza is the only one who had the nerve to testify against Abarca and reveal the mayor’s ties to the drug rings, even before the tragedy of the missing students took place. Mendoza’s testimony is key to Mexican prosecutors’ case against Abarca, whom they are charging with the murder of Hernández Cardona.

Hours after the mayor and his wife were arrested in Mexico City after a month on the run, and with support from humanitarian groups, Mendoza agreed to talk to a journalist for the first time.

But in his meeting with EL PAÍS, he spoke reluctantly, evidently trusting no-one.

“All that’s left for me to do in life is to run,” he says, sitting in the corner of a bar. Mendoza can barely read and write. His story, punctuated by tense silences, is as follows.

Born in Chilpancingo, in the state of Guerrero, he worked for years as an agricultural laborer before becoming a chauffeur for the engineer Hernández Cardona. In the afternoon of May 30, 2013, he was driving a van down the road to Iguala. Sitting with him in the vehicle were Hernández Cardona and six members of Unidad Popular, all of whom were returning from one of their public protests against Mayor Abarca. A Jeep suddenly cut them off and six armed men got out, aiming their weapons straight at them. Everyone was told to get out of the van. As soon as they did, Hernández Cardona, a man renowned for his untamed spirit, was shot in the right leg. The attackers did not want any resistance. Then they fired seven shots in the air and ordered everyone back in the car. The kidnapping had begun.

The hitmen tied their victims’ hands and took them to a spot in the outskirts of Iguala. They were not alone — other abductees were already there as well. The torture began that same night. First an interrogator came to see them one by one. “He wanted to know why we were spray-painting the walls of city hall, why we were attacking the mayor, why we had blocked the road checkpoints...”

When the questions ended, a hitman would slam an iron pipe against their knees, and sometimes lash them with a barbed-wire whip. The black lines on Mendoza Villa’s arms provide evidence of this.

The torment continued into Friday. That day, the kidnap victims held no more doubts as to their ultimate fate. Three were assassinated that same day.

“One had his head chopped off with a machete,” explains the witness.

That night, the mayor of Iguala made his first appearance. He was wearing tight black jeans, a snug dark sweater and a cap. He was in the company of his chief of police.

I could get killed at any moment. All I ask for is protection for myself and my family”

“They watched as we were beaten, without saying a word, just sipping on their beers,” recalls Mendoza. Abarca returned later for another torture session. It was then that he walked up to the leader of Unidad Popular and offered him a bottle of beer. The engineer turned it down. Around 10 meters from that spot, there were some freshly dug pits that the hitmen had made that same afternoon. Everyone knew what they meant.

“Abarca ordered the engineer dragged before one of the pits. Then he began saying: 'Why are you spray painting my town hall, eh? Since you’re screwing me so much, I’m going to have the pleasure of killing you.’”

Hernández Cardona tried to remain standing, and never said a word. “I saw Abarca point at his head, at his left cheek, and shoot. Once the engineer fell into the grave, he shot him again,” says Mendoza.

After the crime, heavy rain began to fall on the spot. The other kidnap victims went into panic and one of them, Rafael Banderas, attempted to flee, but he was quickly caught and killed. The others huddled under the canvas roofing that provided some protection from the storm. Their time had apparently not yet come.

But the next day, the hired gunmen packed them into a Jeep along with the bodies of Hernández Cardona and Rafael Banderas.

“They were worried. People down in the village had begun searching for us, and they wanted to get away,” recalls the witness.

They drove toward the dump in Mescala. When they got out, the two killers in charge of their custody got distracted for a moment, and another abductee, Ángel Román Ramírez, ran away. He did not get far, however, and collapsed in the middle of the road. The hitmen walked up to him slowly to kill him.

That was when the rest of the group saw their chance and made off in every direction.

“I aimed for the trees. I heard six shots but didn’t stop. I thought they would get me, but they didn’t come after me. We spent eight hours in hiding, then stopped a car that took us back to Iguala.”

Once there, the survivors each went their different ways. Only Mendoza Villa dared step up and talk about what he had seen and heard. With help from Hernández Cardona’s widow, he gave sworn testimony of the events. The murder of the engineer and his colleagues created an outrage, the students at the teacher’s college in Ayotzinapa attacked Iguala city hall, and the attorney’s office asked a few questions. But in the end, nothing happened.

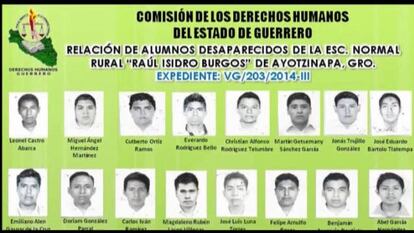

Abarca continued to rule over the city until September 26, when protesting students were caught up in the barbaric events that made world headlines and led to national protests that have put the Enrique Peña Nieto administration in a tight spot.

Now, the Attorney General has reopened the case of the murdered engineer and backed Mendoza’s testimony.

“But I could get killed at any moment,” he says. “All I ask for is protection for myself and my family.”

Mendoza Villa, 44, has a wife and four children. Several times during the course of the interview he hesitated and thought of cutting it short. He is still scared of Abarca, even now the mayor is behind bars.

—Do you ever plan to return to Iguala?

—Never. That place is hell.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.