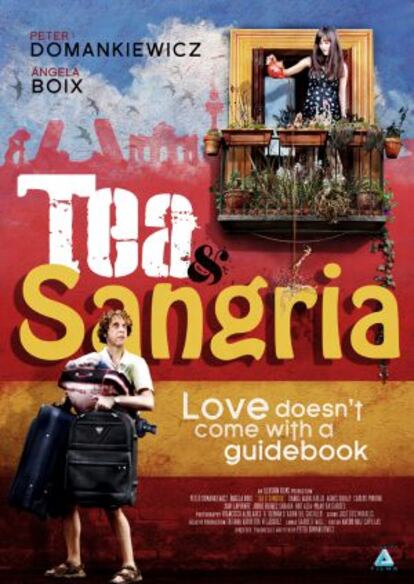

A microbudget love letter to Madrid

Anglo-Spanish romcom ‘Tea & Sangría’ is about to receive its premiere – in northern France

The town of Dinard in northern France is an elegant seaside resort of around 10,000 inhabitants, once favored by the likes of Winston Churchill and Pablo Picasso.

Those illustrious connections aside, it doesn’t seem the most obvious spot to premiere a culture-clash Anglo-Spanish romcom shot by a British director in Madrid with the kind of resources that make your average micro-budget feature look like a Michael Bay blockbuster.

Except that Dinard also plays host to a petite but prestigious festival dedicated to British film. And at this year’s edition, which kicks off on October 8, alongside new works from established talents such as Mike Leigh (Mr Turner) and Michael Winterbottom (The Trip to Italy), its Catherine Deneuve-headed jury will also be able to witness the official unveiling of the minuscular Tea & Sangría.

The first two weeks, we lost every important member of the crew. Some of them two or three times over”

It all makes the film’s writer-director-producer Peter Domankiewicz a very happy man indeed. He first wrote his story about an Englishman who gives up everything to live with his Spanish girlfriend in Madrid, only for the relationship to turn sour, back in 2008, inspired by his own experiences of moving to the Spanish capital. “Everybody said they liked it, everybody said they thought it was funny – nobody went for it,” he says of his first efforts to tout it to Spanish producers.

The rejection prompted an extreme decision. An experienced director back in the UK with several short films, TV dramas and commercials behind him, Domankiewicz was keen to step up to features and spotted his chance: “I just said, that’s it, I’m making it myself.”

Ransacking his savings to purchase equipment, shooting permits and food to bribe his Spanish actor and filmmaker friends into helping him, he quickly put the wheels in motion.

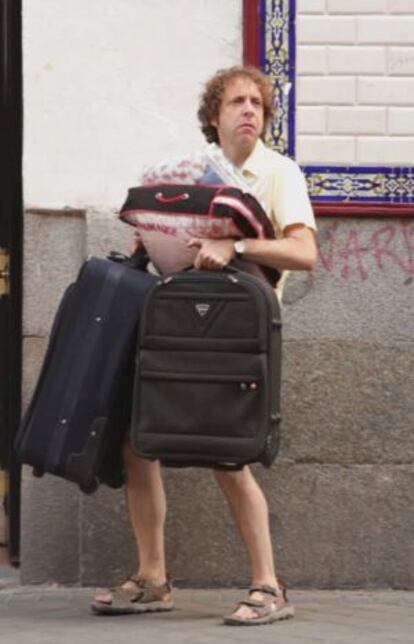

Who, though, to play the lead role of the broken-hearted Englishman learning to find his way in a foreign city? It screamed out for a Simon Pegg-type, but with no cash and a few acting classes recently under his belt, he saw no choice but to cast himself.

Working as his own director was no sweat, he explains. The problem was juggling everything as well. “What is hard is literally, between one shot and the other, having to run out of the building where you are, run down the street to a cash point, take out €200 from your account, run back, give it to somebody and tell them go somewhere, do something, or pay somebody, and then get back into character and step back in front of the camera and carry on the scene. That is enough to push you into a nervous breakdown.”

The result was near disaster. The unorthodox working methods necessitated by the microscopic budget – a “flexi-crew” that often didn’t consist of more than five or six people; handheld shooting on a digital SLR camera; the minimum of takes; moving between locations by Metro – didn’t always sit well with some of the film school grads who’d originally signed up and been trained to make movies in a particular way. “The first two weeks, we lost every important member of the crew,” he remembers. “Some of them two or three times over. It was the most horrendous shooting period I’ve ever had.

He almost gave up, he admits. The lowest moment came sitting outside an Indian restaurant on Lavapiés street at 1am after a particularly tough day’s filming. “I can remember just sitting there weeping and eating Indian food with people walking by paying no attention to me. All on my own. With the whole thing now on my shoulders. Just actually thinking Peter, you HAVE bitten off more than you can chew. You cannot make a film with almost no money at all and a bunch of relatively inexperienced actors and crew and really no good reason why they should even work for you for nothing.”

Gradually, though, with the help of actress Ángela Boix, who plays his on-off girlfriend Marisa in the film, and Colombian production manager Tatiana Arboleda, he assembled around him the people he needed to move forward.

You’ve got English people talking bad Spanish, Spanish people talking bad English, as that to me was life in Spain”

If anything, the small-scale shoot – Domankiewicz is coy about revealing the precise final cost but admits it was under six figures – made filming in the middle of Madrid even easier. No one batted an eyelid as they shot a scene of him carrying a passed-out Boix through busy Puerta del Sol: “I think the take in the film is the second or the third and still everybody’s looking at us. If you watch all the crowd, they’re looking at us like she’s really passed out and not looking at the bloke with the camera. Because he could just be somebody in the crowd who’s pointing their camera at it. […] Very rarely did we have the issue that members of the public interfered.”

The end result – shaped with the help of the Goya-winning editor of Alejandro Amenábar’s The Others, Nacho Ruiz Capilla, who signed up simply because he liked what he saw – is an Englishman’s rough-round-the edges love letter to Madrid: the cinematic equivalent of a billet-doux crafted on a paper napkin.

The plot might feature its fair share of outrageous turns – though he says some of the more bizarre moments were true – but it’s often spot on when it comes to picking apart British and Spanish cultural differences: the difficulties of explaining vegetarianism to a Spaniard; the excessive politeness of British speech – “everything is apologizing” – and even contrasting attitudes to breaking wind.

Compounding the authentic feel is the fact that, unusually, this is also a properly bilingual film. A Hollywood version would no doubt have wangled a way to get everyone into talking English, but here the characters use both languages, as they would in real life. “You’ve got English people talking bad Spanish, Spanish people talking bad English, just a whole mix of stuff going on all the time, because that to me was life in Spain. This strange mash-up,” says Domankiewicz, who also took the decision to integrate the subtitles into the heart of the frame, rather than pasting them below, to keep your eyes focused on the onscreen action.

With Britain filling further up with Spaniards and Britons making an extraordinary 14 million trips a year to Spain, the close relationship between the two countries that has inspired and driven the film this far is only getting closer. “There is no comparison in the whole of Europe with any group of people spending so much time with another,” he points out, now back living in London after his Madrid sojourn. It’s something that makes him hopeful the film can go further still after Dinard and score a decent distribution deal in the UK, Spain and beyond.

One big question remains, though: knowing what he knows now, would he do it all again? There’s no hesitation: “Like this? No, no way! I was mad!” Taking so much on was a means to an end, a bid to dig himself out of development hell and stop sitting around waiting for opportunities to come out of thin air, he says. “There’s only so long you should be there with your hand out, going ‘give me a subsidy, por favor.’ You’ve sometimes got to make it happen.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.