The mystery of El Azul deepens

Mexican authorities investigate possible death of a Sinaloa cartel leader

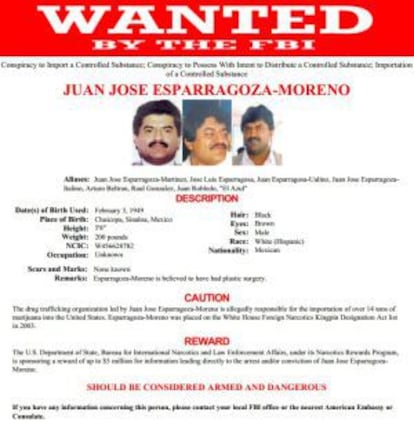

El Azul worked in a business in which a typical boss wears gold chains, keeps a Lamborghini in the garage and a pet leopard by his side. But he always kept out of the limelight. Perhaps Juan José “El Azul” Esparragoza Moreno died just as discreetly as he lived. A high-ranking Mexican official told EL PAÍS that the government is trying to confirm whether the best-known of the great Sinaloa drug lords – a key member within the organization – really died of a heart attack last Friday. He was supposedly cremated on Saturday in a secret ceremony open only to family members.

Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán made the Forbes list of the richest men in the world. The Mexican journalist Julio Scherer interviewed the legendary Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada. El Azul, the third pillar of the powerful Sinaloa mafia, has always kept a lower profile. His file at the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) describes his activities as “unknown.”

El Azul’s nickname came from his appearance. His skin was so dark that his friends said he was blue. Despite being a wanted man in Mexico since 1998 and in the United States since 2003, Esparragoza Moreno has managed to outlive several generations of drug lords who ended up dead or in prison.

Unlike other capos, El Azul’s supposed death was nothing spectacular. Río Doce, a local newspaper, said he had an accident and suffered severe injury to his hip 15 days ago. On Friday, he had a heart attack as he tried to get up from his bed. His family informed the paper of his death, the article said. El Azul was 65 years old.

Mexican authorities have not confirmed the death. Although they say it is “a rumor,” they have opened a joint investigation with the DEA. “It’s not easy to ascertain whether the ashes belonged to El Azul. His relatives could be trying to trick us so we stop looking for him,” the Mexican official said.

Mexican authorities have not confirmed the death and have opened a joint investigation with the DEA

Esparragoza Moreno made it into the cartel history books long ago – when drug trafficking was almost nothing but a rural business controlled by village thugs. He and other top bosses, like El Chapo and Caro Quintero, were raised in Badiraguato (Sinaloa). El Azul opened a grocery store when he was a teenager and later proved himself to be a skilled livestock trader. At 22 years old, he joined Amado “Lord of the Skies” Carrillo Fuentes and his fleet of small aircraft in carrying large quantities of drugs to the United States. He showed that he was a skilled merchant early on as he handled Sinaloa deals with Colombian cartels, whom the Mexicans needed to deliver cocaine on the other side of the border. He became known as a man who sought consensus.

His proverbial discretion makes it difficult to reconstruct some periods of his life. The writer of Desperados, Elaine Shannon, said El Azul was one of the top drug dealers in the Guadalajara cartel. The organization was founded in its namesake city but its most powerful members were from Sinaloa. Don Winslow used them as inspiration for his book, The Power of the Dog. Guadalajara was dissolved after the death of DEA agent Kiki Camarena. And El Azul was arrested in the mid-1980s for public health offenses. He was sentenced to seven years in jail.

Prison wardens created a detailed psychological profile of the capo. The Mexican newspaper Sin Embargo has published the text online. Those who observed Esparragoza Moreno said he had psychotic tendencies but he was not insane. They said he was independent and non-conformist. He was not impulsive and he did not show “inappropriate” feelings. He was active, energetic, and had difficulty accepting the rules. The answers he gave during a test reflect his ambiguous personality:

61. I have not lived rightly: True

102. My toughest battles are against myself: True

201. I wish I were not so shy: True

249. I have never had run-ins with the law: True

Various articles and publications chronicled Esparragoza Moreno’s dissolute life in jail. He served out his time in Reclusorio Sur, a Mexico City prison known as “Beverly Hills.”

The inmates walked around the halls with those first cellular phones – the ones that were so large they had to be carried in a suitcase. There was a television and a microwave. The bosses celebrated the communions of their children there. El Azul gave the authorities a private home on Fuego street in southern Mexico City. The house was in a quiet upper-class area. The Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, who died in March, lived in that neighborhood for 30 years.

If El Azul really passed away, then he did so without the fanfare that accompanied other Sinaloa natives like Arturo Beltrán Leyva, whom soldiers gunned down with assault rifles in 2009. El Chapo was picked up by drones as he fled between drainpipes in Culiacán. Now they say the ashes of that secretive man, El Azul, live on a mountain top in Sinaloa.

Translation: Dyane Jean François

Future of Sinaloa cartel unknown

The departure of El Azul raises even more questions about Mexico’s most powerful cartel, Sinaloa. The capture of El Chapo, the most wanted man in the world after Bin Laden, led to a succession process in February that seems to remain open.

The regional government said the boss’s capture spiked the rate of clashes – from one per day to three – between police officers and criminals. In May, there were more than 100 homicides. The instability in the cartel has turned some areas of the region into a cemetery.

Early Monday morning, authorities found 12 corpses in a van. Six more bodies were discovered in the next few days, bringing the total of dead to 18 within one week. Armed men and police clashed on Los Mochis-El Fuerte highway but officials have not said whether there were any casualties. With El Chapo behind bars and El Azul allegedly turned into ashes, the only historical figure in the business is El Mayo Zambada. He has been in the drug trade for 50 years without ever serving time in prison.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.